It’s now been seven years since I first started exploring a simple hypothesis:

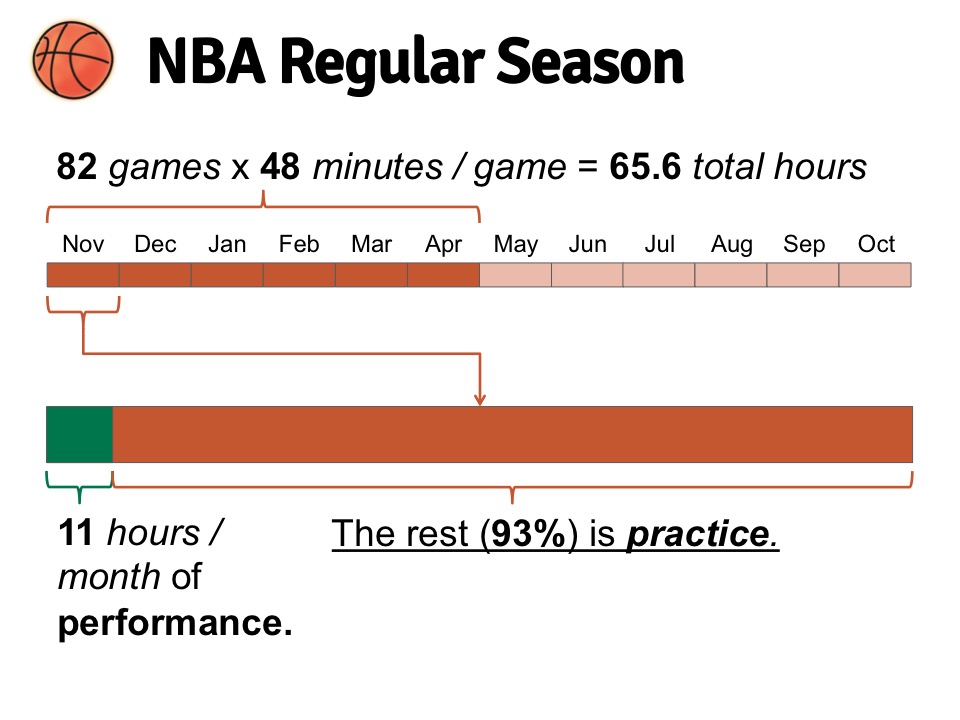

- Collaboration is a muscle (or, rather, a set of muscles)

- You strengthen these muscles by exercising them repeatedly (i.e. practice)

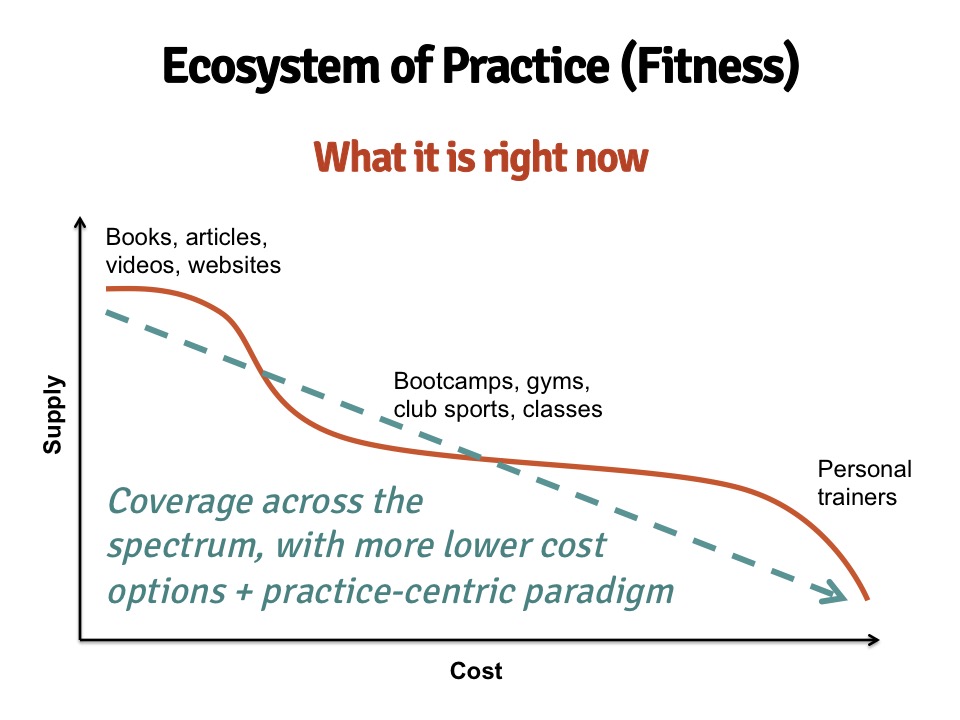

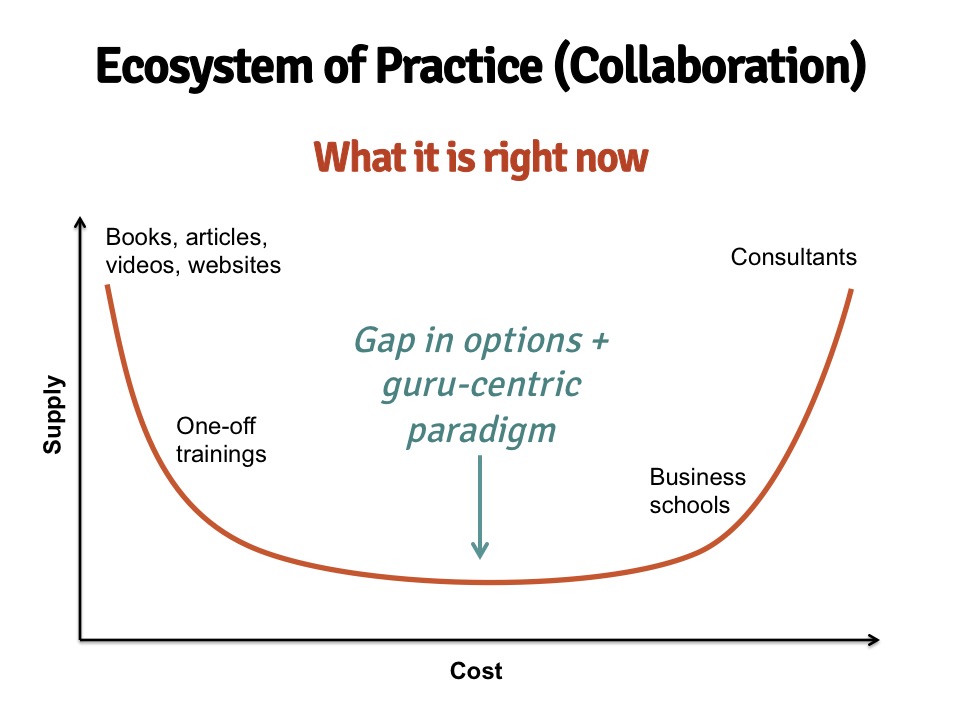

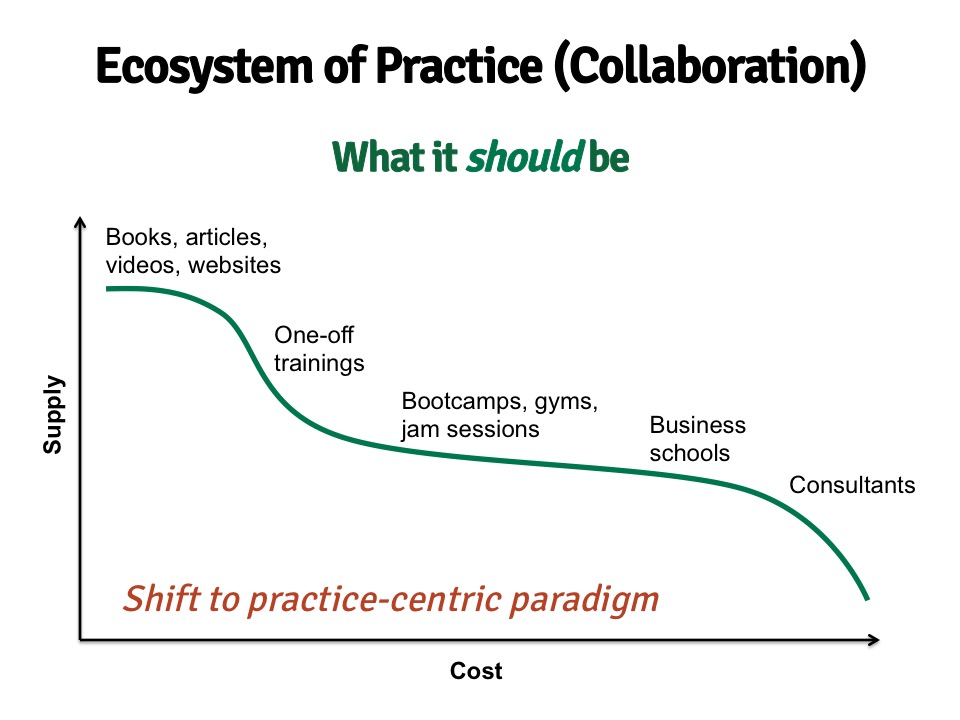

Our current orientation toward collaboration is knowledge-centric, not practice-centric. No one expects anyone to get good at playing the guitar by handing them a book or sending them to a week-long “training,” yet somehow, this is exactly how we try to help folks get better at communicating or navigating hairy group dynamics.

I’ve spent the past seven years trying to change this. I’m currently on the fifth iteration of my experiments, which I’m currently calling Collaboration Gym. The other iterations (slightly out of order) were:

- Changemaker Bootcamp (2013)

- Collaboration Muscles & Mindsets (2014-2015)

- Habits of High-Performing Groups (2018-present)

- “Personal” Training for Organizations (2016-present)

- Collaboration Gym (2020-present)

I’ve failed a lot and learned a ton with each iteration, and I thought it would be fun to summarize what I’ve been learning here. I’ve also been having provocative conversations with Sarna Salzman and Freya Bradford about what a Collaboration Gym (or, in their case, a “Systems Change Dojo”) might look like in their community of Traverse City, Michigan. We’ve stayed mostly big picture so far, but recently decided that it was time to get real and specific. With their permission, I’ve decided to do my thinking out loud so as to force me to write down these scattered thoughts and also get some early feedback from a broader set of folks. That means you, dear reader! Please share your thoughts in the comments below.

Changemaker Bootcamp (2013)

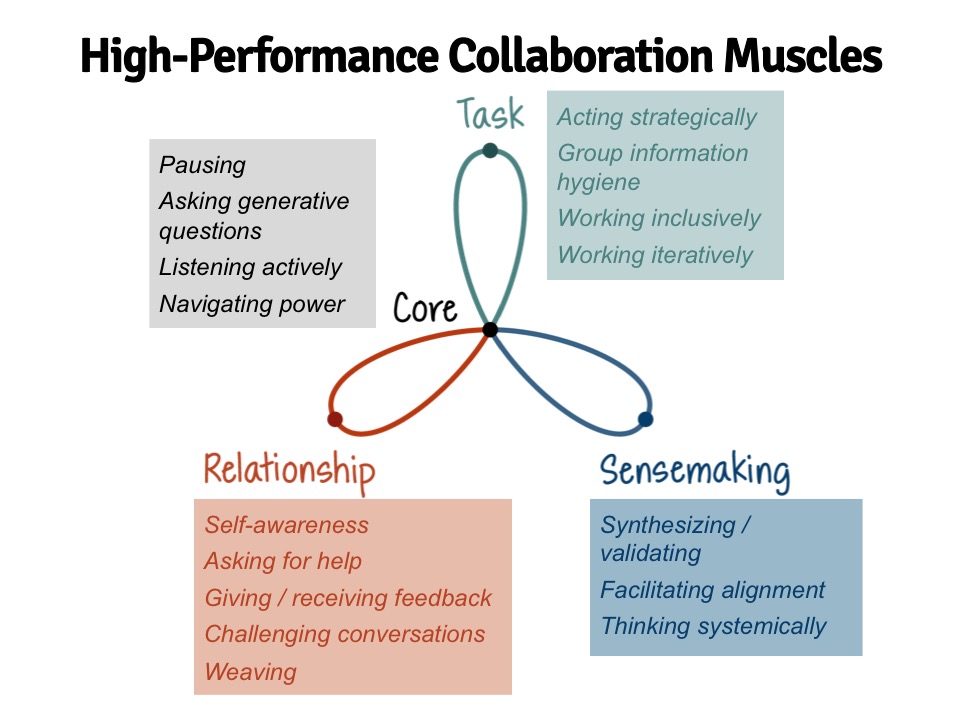

The first iteration of this experiment was Changemaker Bootcamp, a face-to-face workout program that met for two hours every week for six weeks. I designed a series of exercises focused on developing muscles I considered to be critical for effective collaboration, such as listening actively, asking generative questions, navigating power, and having challenging conversations.

My participants — all of whom enrolled individually — generally found the exercises valuable and appreciated the practice-orientation. They also got along well with each other and valued the peer feedback. I designed the workouts to feel like physical workouts, only without the sweating and exhaustion. They consisted of warmups followed by intense exercises, with “just enough” explanations for why we were doing what we were doing. Most found the experiential emphasis refreshing. A few found it slightly dissatisfying. Even though they trusted me, they still wanted me to explain the why of each workout in greater detail.

These initial pilots helped me test and refine my initial set of workouts, and they also helped build my confidence. However, there were three key flaws.

- We weren’t repeating any of the exercises. In order to do this, I needed more of my participants’ time and I needed to focus my workouts on just a few core muscles.

- I needed an assessment. This would help me figure out the muscles on which to focus, and it would also help participants sense their progress.

- I was having trouble explaining the specific value and impact of this kind of training to people who didn’t already know and trust me.

Collaboration Muscles & Mindsets (2014-2015)

I tried to address these flaws in my next iteration, Collaboration Muscles & Mindsets. I almost tripled the length of the program from six to 16 weeks to create more space for repetition and habit-building. I created an assessment that folks would take at the beginning and at the end of the program, which helped me focus the workouts and also enabled the group to track their progress. Finally, I made it a cohort training rather than a program for individuals, which also helped with focus.

I also shifted the trainings from face-to-face to a remote, decentralized model, where I paired people up and made them responsible for scheduling their workouts on their own. After each workout, folks would share one takeaway on an online forum. This created group accountability by signaling that they were doing the workouts, but it itself was also a workout focused on muscles for sharing early and often. Every four weeks, everyone would get together for a full group workout.

Not being face-to-face meant I couldn’t (easily) do somatic workouts and that the instructions had to be clear and compelling. Not leading the pair workouts meant that I couldn’t make real-time adjustments. These constraints forced me to be more rigorous in designing and testing my workouts. In return, doing them remotely made it easier to participate and shifted agency away from me to the participants, which was in line with my desire to de-guru-fy this work.

I consistently faced early resistance from folks about the time commitment. I tried to explain that the workouts were in the context of the work that they were already doing, so they weren’t actually doing anything “extra,” but reception to this was mixed. Even though people got the metaphor around practice and working out, they didn’t have their own felt experiences around what this might look like, which made my description of the program feel abstract.

In the end, I asked participants to trust me, explaining that they would be believers after a few weeks. Most folks are hungry to talk about their work with someone who will empathize, be supportive, and offer feedback. Talking with the same person regularly enables people to get to the point faster, because their partners already know the context. Even if folks ignored my instructions entirely and just talked, I knew that they would get value out of simply having regular conversations with other good people.

This almost always turned out to be true. After the first week of workouts, folks would generally report having an excellent conversation with their partner. After about six weeks, people would often start saying that their workouts with their partners were the highlights of their week. Even though people generally had a felt sense of progress by the end of the program, they especially loved the final assessment, because they could point to and talk about the progress they had made in a concrete way.

Collaboration Muscles & Mindsets was a vast improvement over Changemaker Bootcamp, but people were still not practicing enough to see the kinds of dramatic, persistent improvement I wanted to see. I needed to focus the workouts even more and find ways to get people more repetitions.

I was also still having trouble explaining how doing these workouts would lead to the promised impacts. People understood the theory, but without felt experience, it felt too abstract. If you think about it, telling folks who are out-of-shape that they could be running a 5K in two months simply by running a little bit every day also feels abstract and far-fetched. The reason people are willing to believe this, even without felt experience, is that they know that many others have done it successfully. I probably need to get to the same place before folks truly believe the story I’m telling about collaboration muscles and practice.

Habits of High-Performing Groups (2018-present)

In 2018, I decided to shift the frame of my trainings to focus on four habits of high-performing groups:

- Aligning around success

- Aligning around working agreements

- Retrospectives

- Information hygiene

Throughout the course of my work with groups of all shapes and sizes, I noticed that the best-performing groups do all four of these things consistently and well. These also serve as keystone habits, meaning that doing them regularly often unlocks and unleashes other important muscles and habits. Regularly trying to align around anything, for example, forces you to get better at listening, synthesizing, and working more iteratively. Only having four habits made focusing my workouts much easier.

My monthly Good Goal-Setting Peer Coaching Workshops was an attempt to help people strengthen their muscles around the first habit — aligning around success. Participants were asked to fill out a Success Spectrum before the workshop, then they got two rounds of feedback from their peers and optional feedback from me afterward. People could register for individual workshops, or they could pay for a yearly subscription that enabled them to drop into any workshop. The subscription was priced low to incentivize regular attendance.

Almost 30 percent of registrants opted for the subscription, which was wonderful. However, only 40 percent of subscribers participated in more than one workshop, even though their evaluations were positive, which meant that the majority of subscribers were essentially paying a higher fee for a single workshop. One subscriber didn’t show up to any of the trainings, which made my gym analogy even more apt.

Another subscriber attended four trainings, and watching her growth reaffirmed the value of this muscle-building approach. However, not being able to get more folks to attend more regularly — even though they had already paid for it — was a bummer.

I think I could leverage some behavioral psychology to encourage more repeat participation. One trick I’m keen to try is to have people pay a subscription fee, then give them money back every time they attend a workout. I also think cohort models, like Collaboration Muscles & Mindsets, are better at incentivizing more regular attendance.

The most negative feedback I got from these trainings was that some participants wanted more coaching from me as opposed to their peers. I designed these trainings around peer coaching as part of my ongoing effort to de-guru-fy this work. Just like working out with a buddy can be just as effective for getting into shape as working out with a personal fitness instructor, I wanted people to understand that making time to practice with anyone helps develop collaboration muscles. Still, I think there’s an opportunity to strike a better balance between peer feedback and feedback from me.

In this vein, this past year, I started offering Coaching for Collaboration Practitioners as a way to help leaders and groups develop the four habits of high-performing groups. This has been my most effective muscle-building approach to date, which makes me somewhat ambivalent. On the one hand, I’m glad that acting as a personal trainer is effective at getting people to work out. On the other hand, not everyone can afford a personal trainer. We need more gym-like practice spaces if we’re going to help folks at scale.

“Personal” Training for Organizations (2016-present)

Finally, over the past five years, I’ve been experimenting with customized organizational workouts focused on specific needs, such as strategy and equity.

I’ve found decent success at convincing potential clients to let me take a muscle-building approach toward their work. For example, rather than help a client develop a strategy, I will lead a client through a series of workouts designed to strengthen their muscles for acting strategically. Still, I often have to strike a tricky balance between more traditional consulting and this workout approach.

I’ve gotten much better at striking this balance over the years. In the early days, I tried partnering with other consultants to handle the more traditional work so that I could focus on the training. That almost always failed, especially with more established partners, because they didn’t fully get and believe in my approach, and in the struggle to find the right balance, the workouts would usually fall by the wayside.

Working by myself allowed me to be more disciplined in my approach, but I still struggled to maintain the right balance, and I failed a lot. I feel like I’ve only begun to turn the corner in the past few months. One thing that’s helped is getting much clearer about what clients need to already have in place in order for the muscle-building approach to succeed, specifically:

- Alignment around the what, why, and how

- Structures, mindsets, and muscles to support their work

For example, attempting to help a group develop muscles when they don’t have the right structures in place can cause more harm than good. To help demonstrate what happens when you’re missing one of these critical ingredients, I created a model inspired by the Lippitt-Knoster Model, to which Kate Wing introduced me:

| Alignment | Structures | Mindsets | Muscles | = | Performance |

| Alignment | Structures | Mindsets | Muscles | = | Confusion

“Why are we doing this?!” |

| Alignment | Structures | Mindsets | Muscles | = | Frustration

“We can’t succeed in these conditions.” |

| Alignment | Structures | Mindsets | Muscles | = |

Resistance “I don’t want to be doing this.” |

| Alignment | Structures | Mindsets | Muscles | = |

Anxiety “We’re not capable of doing this.” |

Collaboration Gym and Future Iterations

I’m mostly resigned to more “personal training” work, if only to accumulate more Couch-to-5K-style success stories, so that people can develop more faith in the muscle-building approach. (If you or your organization would like to hire me for coaching or to design a custom workout program, drop me an email.) But I continue to be committed to experimenting with more scaleable and affordable approaches to muscle-building than hiring personal trainers. I’m hoping to unveil the Collaboration Gym early next year, and I’ve already successfully piloted a number of new workouts that will be part of it.

Epic success for me is to see others participate in similar experiments on their own and to share what they learn. A Collaboration Gym is only useful if there are lots of gyms all over the place. I give away all of my intellectual property so that others can copy and build on it, and I will continue to share my learnings here to further encourage replication.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS