Editor’s Note: I am constantly on the lookout for great collaboration practitioners who share my values and whom I can learn from and practice and partner with. I had the pleasure of meeting Anya Kandel two years ago, and I was taken by the quality of her work and the intensity of her inquiry. Her experiences are eclectic, and her thinking and work is powerful. She very graciously agreed to share some of her learnings and questions here. This has also been cross-posted on Medium, where you can follow Anya’s other writing. This is the second of a four-part series. Part one was, “Understanding Sustainable, Collaborative Change.” —Eugene

For the past three years, I worked to build “innovation capacity” at Gap Inc. The work required us to explore the complexities of driving change within ingrained systems and behavioral norms across multiple communities, teams, and brands. Throughout my time there, I asked myself (and my colleagues) this not so simple question:

How do we build thriving, innovative, and strategically-minded organizations and communities that are sustainably driven by the individuals that comprise them?

I don’t have all the answers of course, but I do have ideas and approaches that worked for me:

- People and context before process and model

- Learn through the work

- Democratize strategic thinking and innovation

- Coordinated access to strategy and culture tools + practice

- Do It Together

1. People and context before process and model

Working at the intersection of innovation, management consulting, and strategy, I witness a big emphasis on model in all these areas. Models are what firms sell in order to scale and what clients use as reference for understanding consultants’ approach and impact. These models, frameworks and processes are important… as tools. But ultimately what makes innovation and strategy consulting firms successful and covetable are the creative, intuitive, and smart people who work there, armed with an understanding of the various processes and techniques that support them to think strategically.

Design Thinking is a good example. It is a rich model and process that works well for many challenges. The philosophy behind the model — one that invites empathy, observation and collaboration in the process of organization and product development — has informed the way we think about problem solving, particularly in the world of business. But, IDEO, grounded in David M. Kelley’s Design Thinking approach, does not sell multi-million dollar projects simply because companies want to buy this model. (It is already accessible and free.) Organizations keep coming back to them because they have a diverse set of creative, strategic, and dedicated people who (with a robust toolkit and lots of experience) can approach every client request in a unique way.

The models (especially sold by innovation firms) aren’t as different as one might think. The power is in the people (those who facilitate, those who participate, and those who work to bring new ideas to life). A good strategic practitioner understands the people and the context, and pools the resources they need to design a process that works best for that specific case. A good approach enables the client / participants to understand the context of various scenarios and problems, ask good questions, and match processes models to context. A good outcome is when an organization, team, or community has the capacity to learn and grow from the experience and continue to evolve the work on their own.

2. Learn through the work

During my time at Gap Inc., I worked to build an internal innovation consulting group. We facilitated teams to solve complex challenges, we designed trainings and systems in order to grow innovation capacity, and we helped teams solve complex business challenges and create new products. In our work, there was certainly no lack of innovative ideas. That was the easy part. The hard part was creating vision and environment where those ideas could surface, as well as a culture that supported ongoing experimentation to help bring those ideas to life.

Initially, we spent much of our time fixing things that weren’t working (rethinking products, systems, and ways of working) and facilitating sessions that solved immediate problems. In parallel, we began to train employees within the company in creative group facilitation, building a force of innovation catalysts. They learned through the “work” of managing innovation projects and co-facilitating with us.

The projects that stuck and the initiatives that had the biggest impact were always those that allowed the catalysts and the collaborators to be the work, instead of receive it. This required them to solve real challenges and test new ways of working in a safe environment.

One of my favorite experiences came during an innovation initiative with a creative leader in store experience and design. We introduced her to a co-creation process, where customers worked collaboratively to evolve what she and her team created. It was amazing to see the shift from theoretical appreciation to active engagement, from the fear of getting something wrong to the discovery of new creative ways of working. From then on, she was able to integrate co-creation and prototyping into her work, recognizing not only the feeling of creative breakthrough, but the visceral understanding of how hard it can be to bring those ideas to life.

Still, given the size of the company and the scale of work we had, our engagements were often confined to executive leadership or isolated teams. Working solely with leaders to build a culture of innovation based on yearly priorities is not enough. Inevitably, leadership and strategy changes, initiatives are dropped, and the pressure of immediate business needs can trump almost anything, no matter how important we think it is.

“Learning through the work” is imperative, but only as powerful as the people who are enabled to actually do so. It wasn’t that our initiatives weren’t big enough or unsuccessful. Rather, we needed to scale or evolve in order to influence the diverse subcultures and teams within the company. We needed to democratize innovation and build a long lasting culture that celebrated experimentation, collaboration, and strategic thinking.

3. Democratize strategic thinking and innovation

Soon after joining Gap Inc., I started to explore how to create alternate spaces for communication that could scale and that skirted hierarchical limitations.

Soon after joining Gap Inc., I started to explore how to create alternate spaces for communication that could scale and that skirted hierarchical limitations.

I noticed a disconnect between the leadership’s desire to understand Millennials and the overwhelming majority of Millennials who worked inside the company. Here lay a tremendous opportunity to bridge that divide and create environments for open communication between people who were making decisions and the young people who had insight into how those decisions would impact people like themselves. Plus, we are community of people who inherently function in a networked environment — what was naturally part of our lives outside the company often seemed insurmountable inside.

I started a group called the M Suite, a nonhierarchical, transparent network of Millennials dedicated to building co-creation and collaboration across brand and function. Functioning like a node in a network, M Suite connects people in the organization who were looking for creative input and collaboration, with the very large community of people eager to help solve creative challenges and share their perspectives.

Building our own infrastructure became an experiment in establishing networked, collaborative communities functioning within a hierarchical infrastructure. We used ourselves to explore unique models and approaches. We experimented with different ways of meeting, communicating, and solving problems. We tried different models for governance. We tried partner leadership. Eventually we arrived somewhere between a Holocracy and a leadership network, and officially took the form of an ERG.

Because our work was inherently related to change and the way we worked was very different from our surroundings, our presence invited reservations too:

- “What if they don’t know the bigger picture and choose the wrong problems to focus on?”

- “Why spend time building visionary ideas and solutions to complex problems when they don’t have the power to implement upon these new ideas?”

Clearly, the notion of “democratizing innovation” and building networks can feel really scary to organizations that rely on more hierarchical way of working. However, I found that these reservations often highlighted circumstances that already existed (i.e. lack of alignment or unclear vision). We never saw their work undermine high-level strategy, but rather elevate the strategic questions and conversations around it.

Democratizing innovation doesn’t necessarily imply that the work of innovation is everyone’s job or that an organization loses all its structure. Rather, it starts with furnishing everyone the respect and equal opportunity to engage in the creative process and think strategically. By expecting this community of individuals to thoughtfully own their work and ask good questions, we invited them to to engage that way. By giving them the tools to walk into any meeting with a strategic mindset, we created an environment where everyone was more likely to try to understand the broader vision and understand what “alignment” could really look like. In fact, they helped to be catalysts for the leadership team, bringing Millennials from various parts of the company to collaborate on the development of leadership goals and help bring them to life.

The desire to join the M Suite was impressive. People from across the company and around the globe participated, hungry to contribute to the evolution of the company. This fitful enthusiasm also reminded me of the social movements and community networks I have worked with in the past and the challenges their emerging organizers faced. The M Suite was soon confronted with the need to fuel a large number of people with the ability to govern themselves differently from the environment they were situated in and the organizational frameworks they were familiar with.

4. Coordinated access to strategy and culture tools + practice

The transition from a conceptual understanding of new systems for working and the actual act of implementing is often conflated with the apparent necessity to already have that systems in place. Of course, this can’t happen. The transition itself implies a journey from one to the other. And the journey is invariably messy, personal, multifarious, iterative, and nonlinear.

We (M Suite co-founders and new board) were called upon to define how to govern ourselves, while still leading. Our growing network of communities were looking for guidance in how to evolve, potentially in very different capacities. The organizers were hungry for tools and techniques that could help them understand how to lead and facilitate collaborative engagements. Plus, they needed to learn tactical strategies for managing the work while also doing their day job.

To answer that need, we organized trainings in innovation project management, client engagement, and collaborative problem solving. We initiated opportunities for shadowing. (At one point, I had eight people shadowing me in a client intake session.) We organized skill shares. We created opportunities to own projects in partnership with those experienced in leadership. We experimented with online tools. We tried new board structures.

We focused our attention on the development of the M Suite board first. This worked, to a certain extent. We became a community for collective learning and growth, and actively serving on the board became a venue for discovering individual potential. Our board members chose to stay at the company longer than they had planned, thanks to the opportunities we provided; or they left earlier than planned, because of the opportunities they realized. In effect, all of the board members were promoted (or promoted themselves by leaving the company) within a year of serving on the board. The need to cycle in new leadership was a happy consequence, but not always an easy one.

Our projects were successful, we grew internationally, and we gained a good reputation in some pockets of the organizations. But the group also became an oasis, striving to become a movement. And it was at this point that I left the company, along with the brilliant original co-founders of the M Suite, Rona Kremer and Jessica Talbert. If I have any regret, it would be not fully figuring out how to embed networked leadership skills and build the strategic “muscles” and tools so that they could more easily drive the creative process on their own and expand more quickly.

As I step away from Gap Inc., the question remains:

How to enable awesome groups like the M Suite to have impact and thrive? How to find ways for people to experiment and engage with the many tools and resources we already have on hand?

I have a lot to learn in this area, but luckily, I have had the privilege of collaborating with and learning from practitioners who are specifically focused on building accessible tools for capacity building. And against Eugene’s wishes, I am going to have to brag about him in his own blog. (Sorry Eugene.)

Eugene stepped away from his founding role in the consulting company, Groupaya, to tackle this very challenge. For the past four years, he has dedicated his time and energy to understanding how to build organizational culture that allows the individual and the organization to thrive. Through this open experimentation with Fortune 500 companies, government organizations, and leadership networks, he is meeting head-on the very difficult work of long-term change.

Eugene’s work has complemented a deficiency I found in many innovation and co-creation initiatives, including my own: accessible, foundational tools and techniques for individuals to be able to actually practice how to work strategically and collaboratively. These resources are public domain, meant to be tools that everyone can use and evolve within their own context. Also, check out Lisa Kay Solomon’s work, which provides a rich foundation in designing strategic processes. She has two fantastic books: Design a Better Business and Moments of Impact. I have no doubt that all of you have a plethora of other resources too, which I encourage you to share in the comments below.

Eugene’s work has complemented a deficiency I found in many innovation and co-creation initiatives, including my own: accessible, foundational tools and techniques for individuals to be able to actually practice how to work strategically and collaboratively. These resources are public domain, meant to be tools that everyone can use and evolve within their own context. Also, check out Lisa Kay Solomon’s work, which provides a rich foundation in designing strategic processes. She has two fantastic books: Design a Better Business and Moments of Impact. I have no doubt that all of you have a plethora of other resources too, which I encourage you to share in the comments below.

These colleagues have helped me to better understand that matching access to practice is simple but powerful. If everyone has the tools and resources to think strategically, then slowly but surely we can build an ecosystem of individuals and organizations that can thrive together.

5. Do It Together (DIT)

We must create opportunities to build connections that allow us to look beyond “best practices,” models, or frameworks, and utilize each other.

An ecosystem is only as healthy as the biomes within it and the strength of connectivity between them. Beyond the immediate development of communities and teams, my most successful innovation and strategic initiatives have been those that invited people to step out of their own realities (via guest artists, makers, new collaborations) to realize new ways of seeing themselves and possibilities for change.

As a strategist and facilitator, I am increasingly exploring the balance between carrying a group through a transformational experience and curating a set of circumstances and resources that enable a group of people to find what they need in each other. We need both, of course. But if, by the end of our time together, I disappear and they forget to say goodbye, I consider this a success.

In fact, I just received a beautiful invitation for an event hosted by the well-branded M Suite, where they are driving conversation with internal Millennials, external creatives, and all employees. It was a small moment of pride, and I hope that our (the founders) step away has translated into collective greater ownership and autonomy.

The world is made of amazing people doing the work that strategists like myself try to inspire. The more we are not needed, the better. But clearly our work isn’t going away. Many organizations and teams, especially in smaller purpose-driven organizations, seek support but do have the funds and access to strategic coaching that is sometimes required to shift circumstance and behaviors that inspire innovation and change.

So then, how close can we get to putting me out of job? How might we pull back the curtain (often weighed down by the fear of losing IP) and share systems, tools, models and approaches across origination and field?

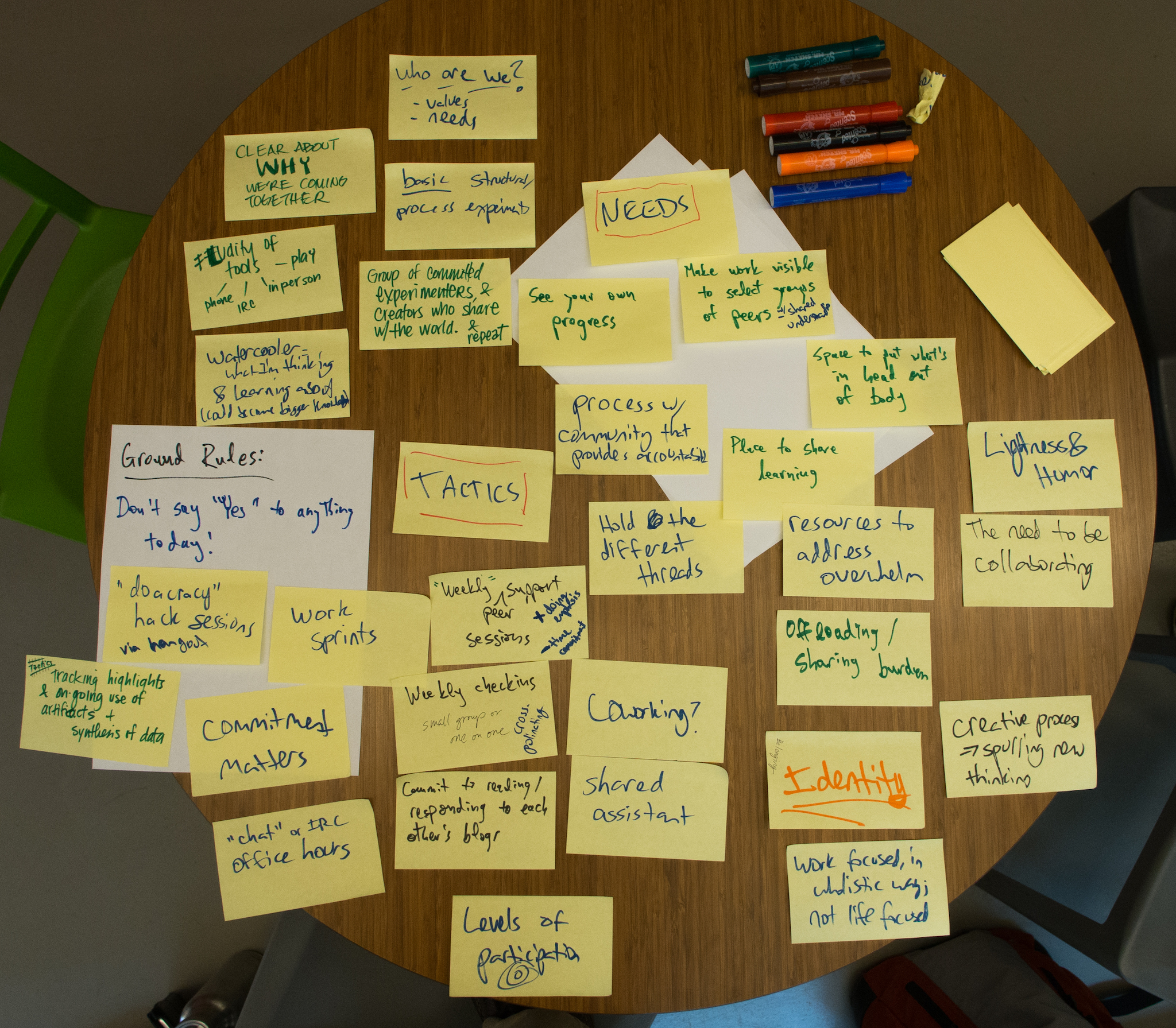

This has been a fun and challenging question to explore with colleagues like Eugene. Drawing on the DIY (Do It Yourself) mentality that utilizes the power of the network for individual development, we are developing strategies to Do It Together (DIT) and ignite the power of peer groups in order to bridge high-level strategic support and training with access to learning communities and support networks.

So far these efforts have resulted in a growing community of practitioners eager to share what they know and grow their personal practice (no matter the industry). Exchanging and fusing approaches has also provided us a great opportunity to challenge the bounds of our own frameworks and tools and think about what it really means to move people and ideas.

There is so much to learn! Please do join us in the experiment. Share your thoughts below. Try Eugene’s tools, and share your own. Join our workshop. Find collaborators in worlds you might not otherwise speak to. And if you are looking to be matched with one, I might be able to help.

Thanks for listening!

This is the second of a four part series. You can also find this post on Medium. Part one was, “Understanding Sustainable, Collaborative Change.”

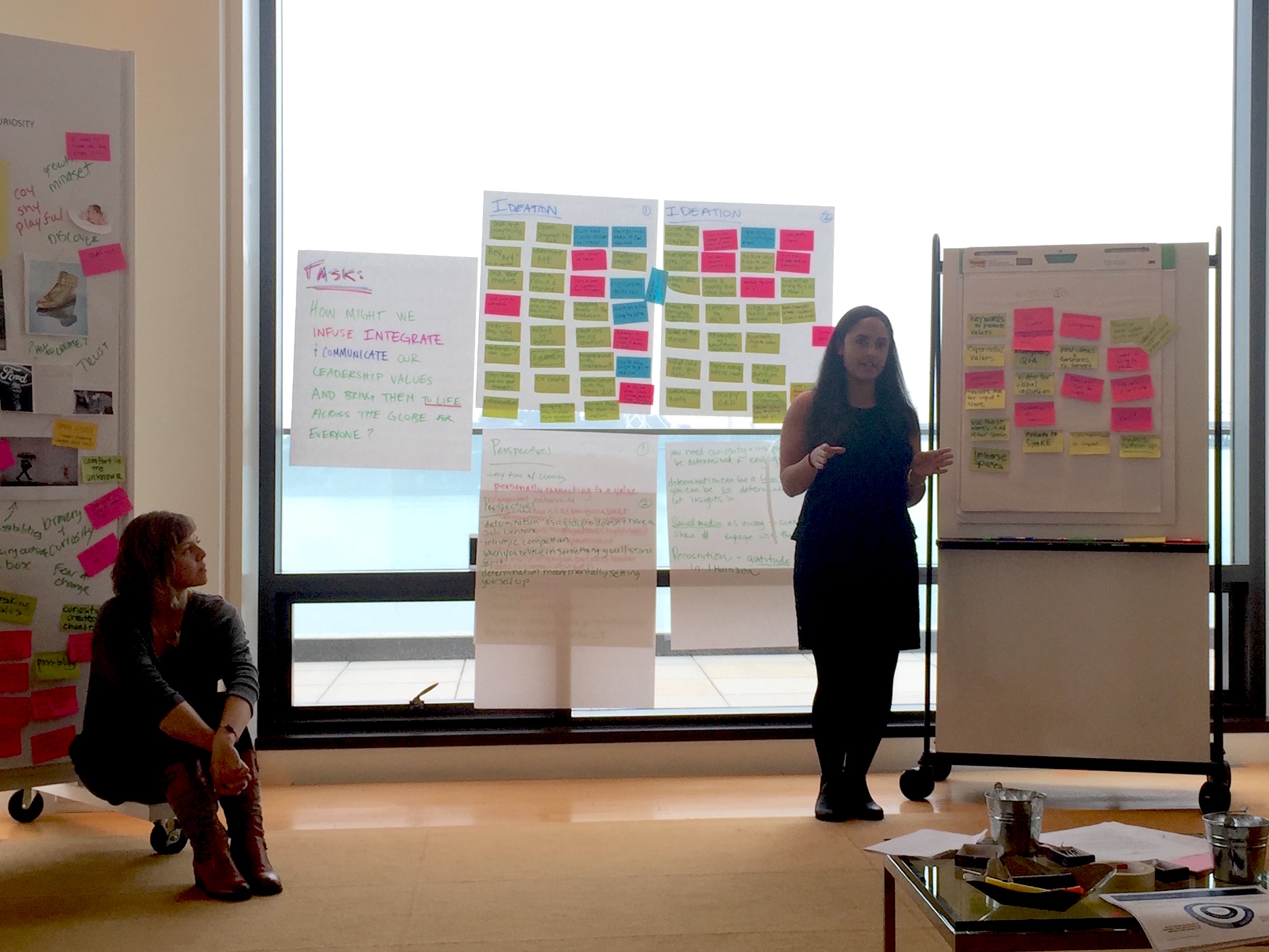

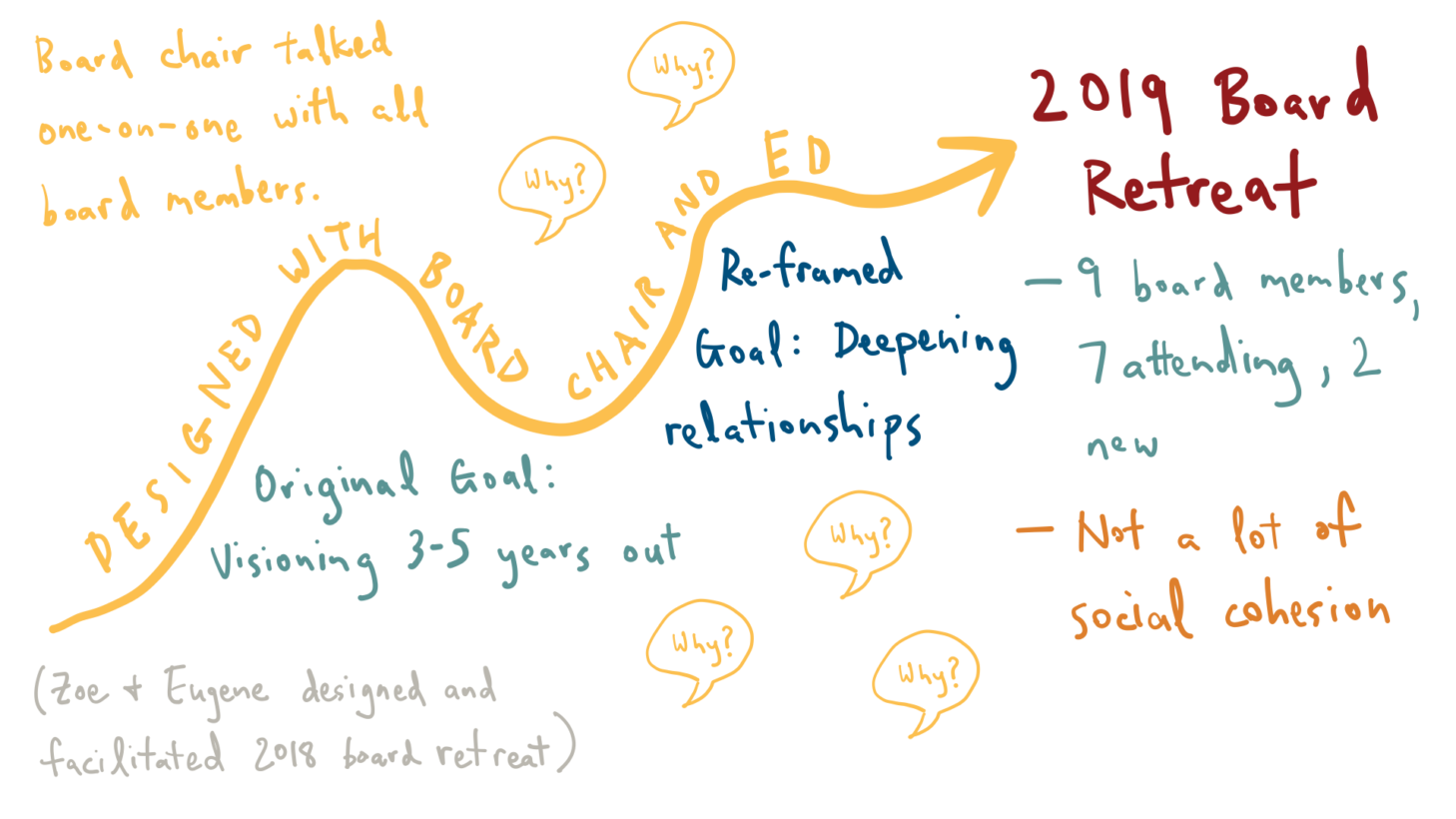

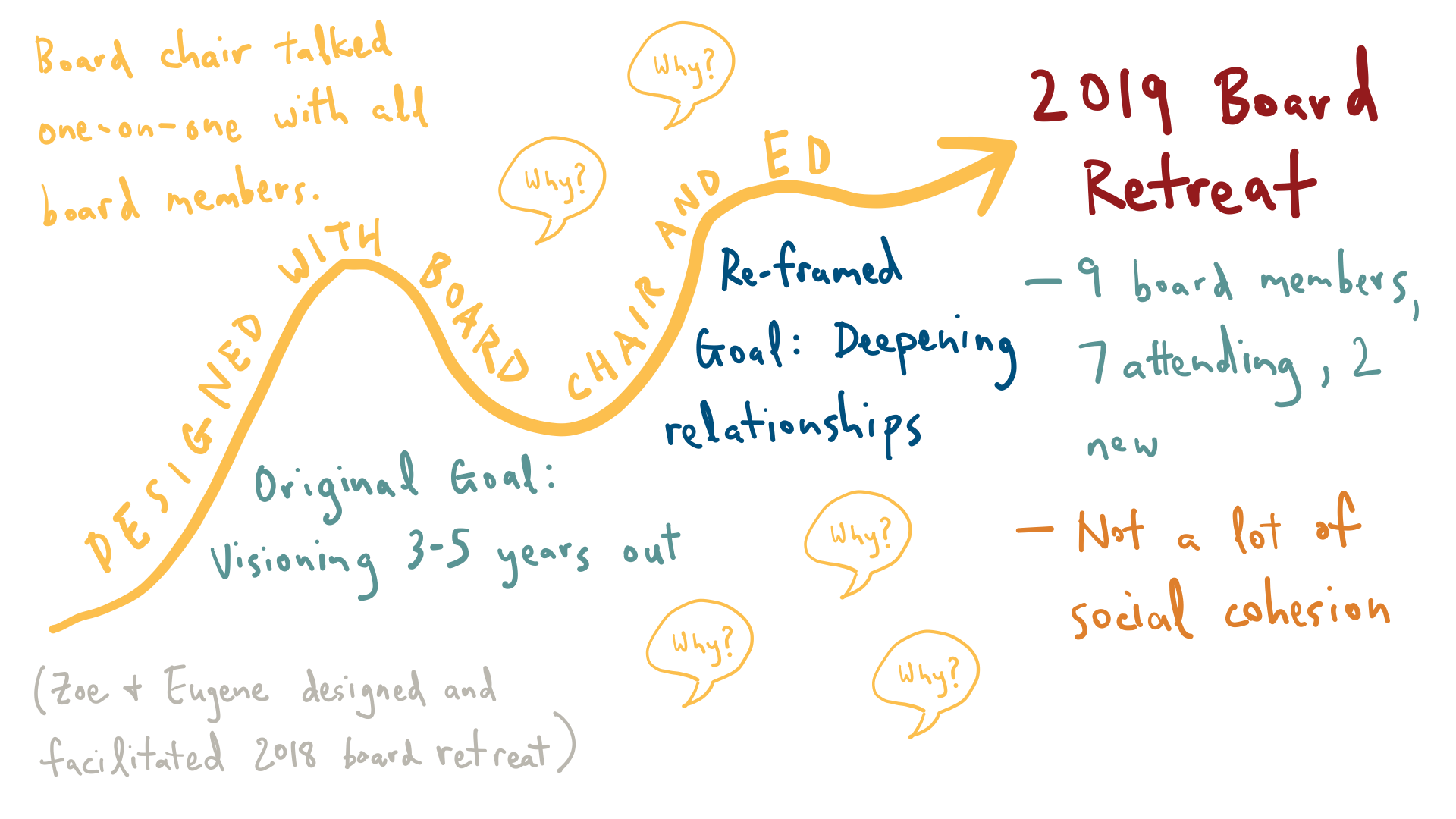

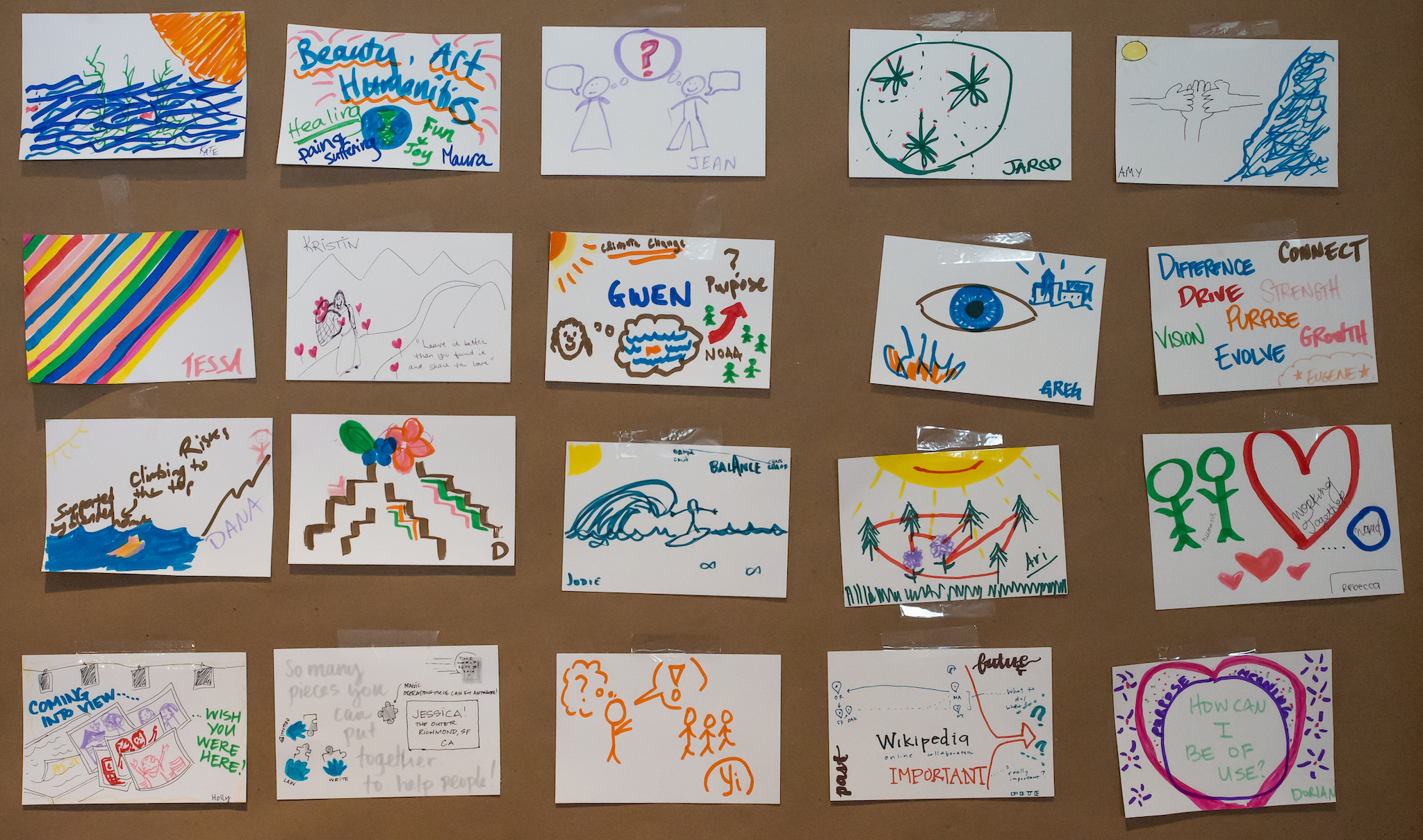

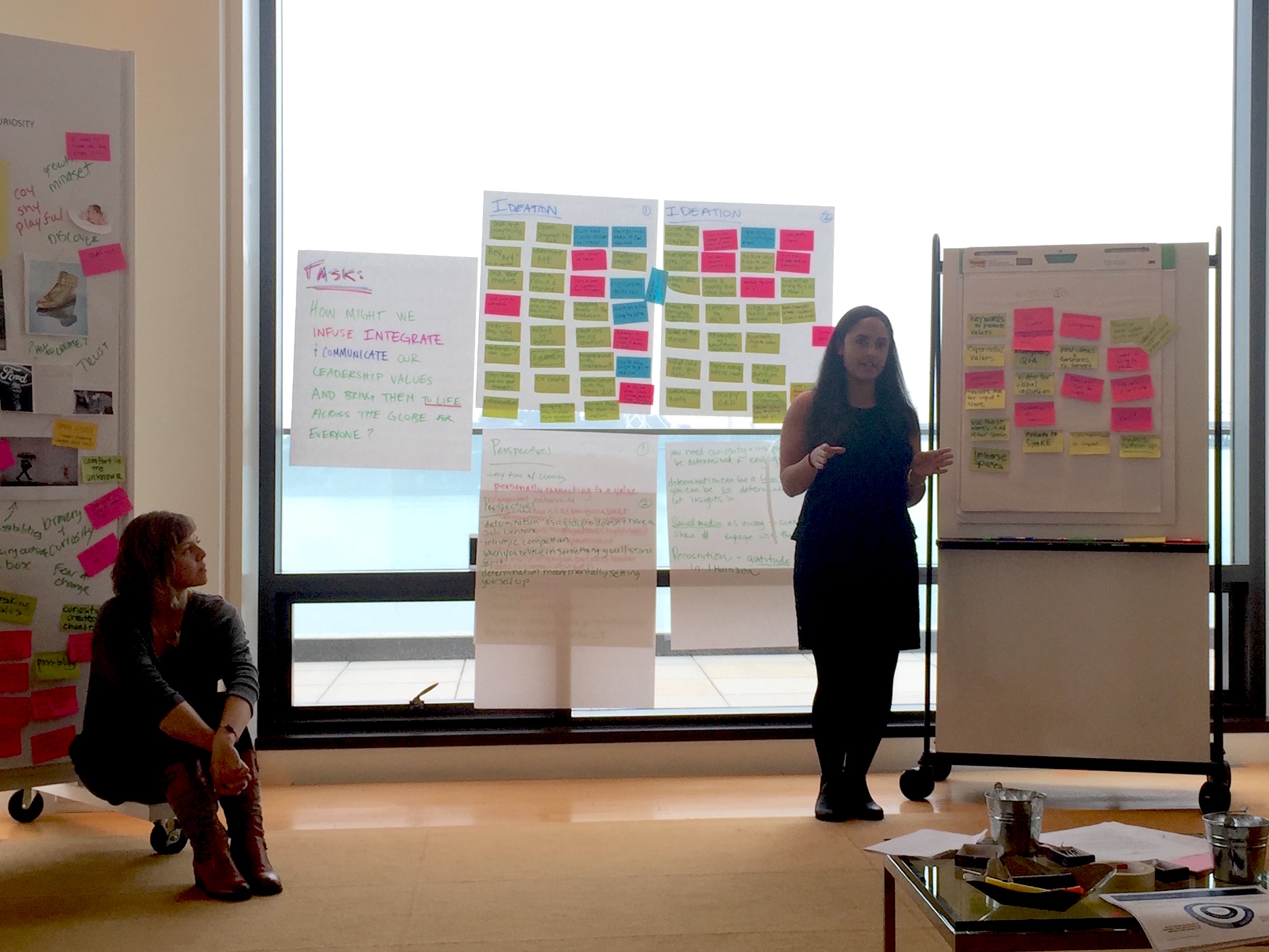

The top photo is of Anya Kandel and Jessica Talbert, Gap Inc. M Suite cofounders. The second photo is of Rona Kremer, another M Suite cofounder. The last photo is from Eugene Eric Kim and Anya Kandel’s October 2016 Do-It-Together Strategy / Culture workshop in New York.

Soon after joining Gap Inc., I started to explore how to create alternate spaces for communication that could scale and that skirted hierarchical limitations.

Soon after joining Gap Inc., I started to explore how to create alternate spaces for communication that could scale and that skirted hierarchical limitations. Eugene’s work has complemented a deficiency I found in many innovation and co-creation initiatives, including my own:

Eugene’s work has complemented a deficiency I found in many innovation and co-creation initiatives, including my own: