Trust. Shared understanding. Shared language. I constantly mention these as critical elements of collaboration. But how do we develop these things, and how do we know if we’ve got them?

We can start by playing Tic-Tac-Toe, then by applying the Squirm Test.

Tic-Tac-Toe

Many years ago, one of my mentors, Jeff Conklin, taught me a simple exercise that gave me a visceral understanding of why trust, shared understanding, and shared language were so important, as well as some clues for how to develop these things.

First:

- Find a partner.

- Play Tic-Tac-Toe.

Try it now! What happened?

Hopefully, nobody won, but don’t stress too much if you lost. It happens!

Second: Play Tic-Tac-Toe again, except this time, don’t use pen or paper.

Try it now! What happened?

In order to play, you needed to come up with shared language to describe positions on the board. You probably managed, but it was almost certainly harder.

Third:

- Play Tic-Tac-Toe without pen or paper again, except, this time, play on a four-by-four board — four rows, four columns.

- Play until it’s too hard to play anymore, until someone has won, or until there’s a dispute about what the board looks like. When you’re done, both you and your partner should draw what you think the board looks like without looking at each other’s work. Now compare.

Try it now! What happened?

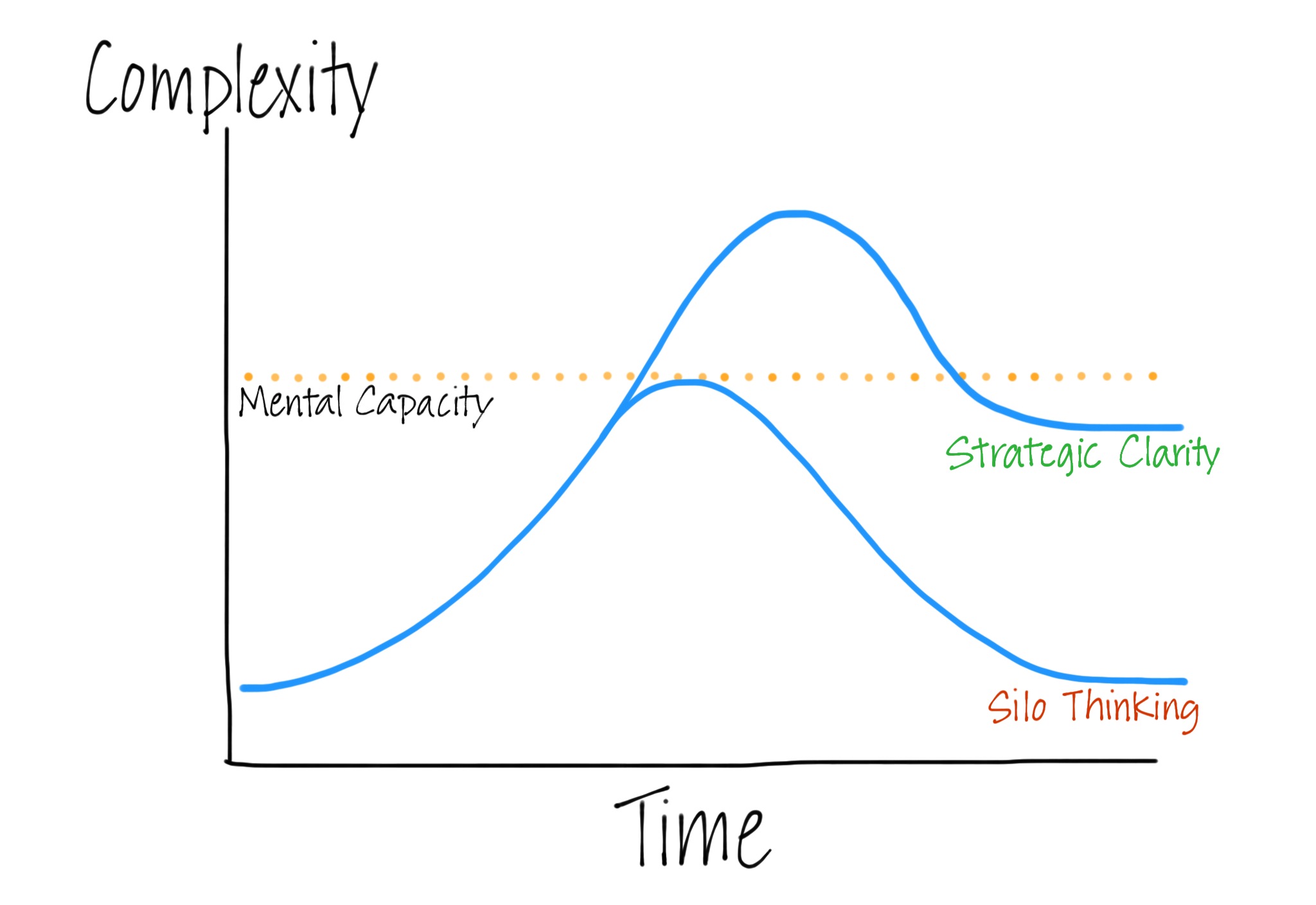

Research suggests that we can hold between five to nine thoughts in our head at a time before our short-term memory begins to degrade. This is why American phone numbers have seven digits. It’s also why three-by-three Tic-Tac-Toe (nine total squares) without pen and paper felt hard, but doable, whereas increasing the board by just one row and column (sixteen total squares) made the game feel impossible.

How many ideas do you think you’re holding in your head after just five minutes of moderately complex conversation? How often are you using some kind of shared display — a whiteboard, a napkin, the back of an envelope — to make sure that everyone is tracking the same conversation?

While you were playing, how much did you trust that the two of you were seeing the same board at all times? Were you right?

In cooperation theory, the most successful groups trust each other by default. You almost certainly assumed that your partner knew the rules of Tic-Tac-Toe and was playing it fairly to the best of his or her ability. If you already had a strong relationship with your partner, you probably trusted him or her even more.

But trust is fragile, and it’s not always relational. If it’s not constantly being reinforced, it weakens. A lack of shared understanding is one of the easiest ways to undermine trust.

With the Delta Dialogues, we were dealing with a uniquely wicked and divisive issue — water in California. As a facilitator, you always want to get the group out of scarcity thinking. But water is a zero-sum game, and no amount of kumbaya is going to change that. Moreover, we were dealing with a half-century legacy of mistrust and a group of participants who were constantly in litigation with each other.

We did a lot of unique, relational work that played an important role in the success of Phase 1 — rotating site visits, asking people to share their favorite places in the Delta, implementing a buddy system, leaving plenty of space for breaking bread. But we were not relying on these things alone to build trust.

Our focus was on building shared understanding through a mapping process that allowed the group to see their ideas and track their conversations in real-time. Prior to our process, the group had been attempting to play multi-dimensional Tic-Tac-Toe with thousands of rows and columns… and no pen and paper. We brought the pen and paper, along with the ability to wield it skillfully.

Like many of my colleagues, I believe strongly in building and modeling a culture where people are engaging in powerful, constructive, sometimes difficult conversation. Unfortunately, it’s not enough to get people into a circle and to have them hold hands and talk about their feelings. The more wicked the problem, the more inadequate our traditional conversational tools become, no matter how skillfully they are wielded.

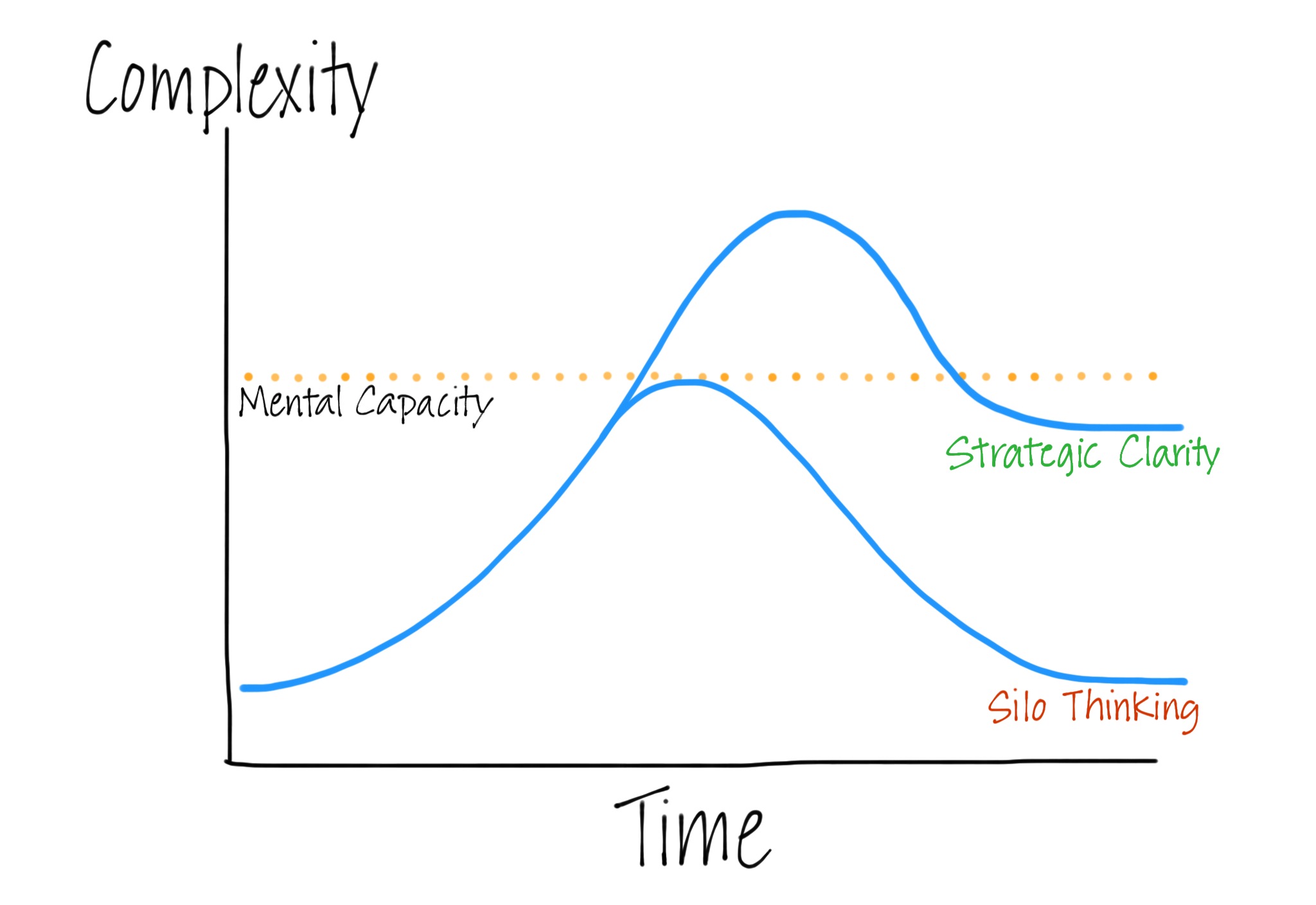

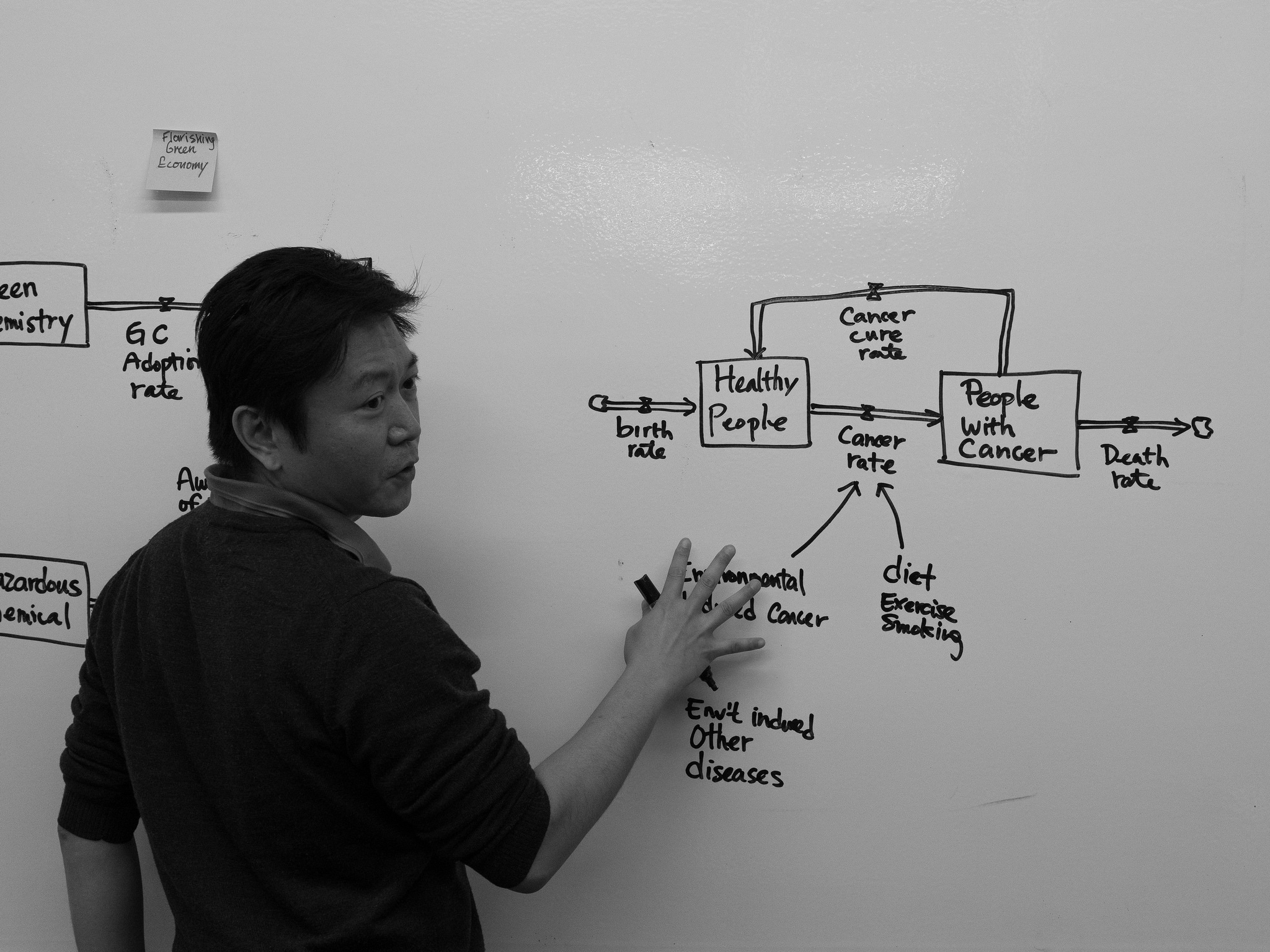

This recognition is what separates the Garfield Foundation’s Collaborative Networks initiative from similar well-intentioned, but misguided initiatives in the nonprofit and philanthropic worlds, and it’s why I’m working with them right now. We happen to be employing system mapping (and the talents of Joe Hsueh) right now as our “pen and paper” for developing that shared understanding, but it’s how and why we’re mapping — not the specific tool itself — that separates our efforts from other processes.

The Squirm Test

How do you know how much shared understanding you have in the first place? And if you choose to employ some version of “pen and paper” to help develop that shared understanding, how do you know whether or not you’re intervention is effective?

Many years ago, I crafted a thought experiment for doing exactly that called the Squirm Test.

- Take all of the people in your group, and have them sit on their hands and in a circle.

- Have one person get up and spend a few minutes describing what the group is doing and thinking, and why.

- Repeat until everyone has spoken.

You can measure the amount of shared understanding in the group by observing the amount of squirming that happened during the presentations. More squirming means less shared understanding.

You can implement the Squirm Test in all sorts of ways, and it even appears in different high-performance communities in real-life. For example, the Wikipedia principle of Neutral Point of View is essentially the Squirm Test in action. If you read an article on Wikipedia, and it makes you squirm, edit it until the squirming goes away. If enough people do that, then that article will accurately reflect the shared understanding of that group of people and will thus achieve Neutral Point of View.

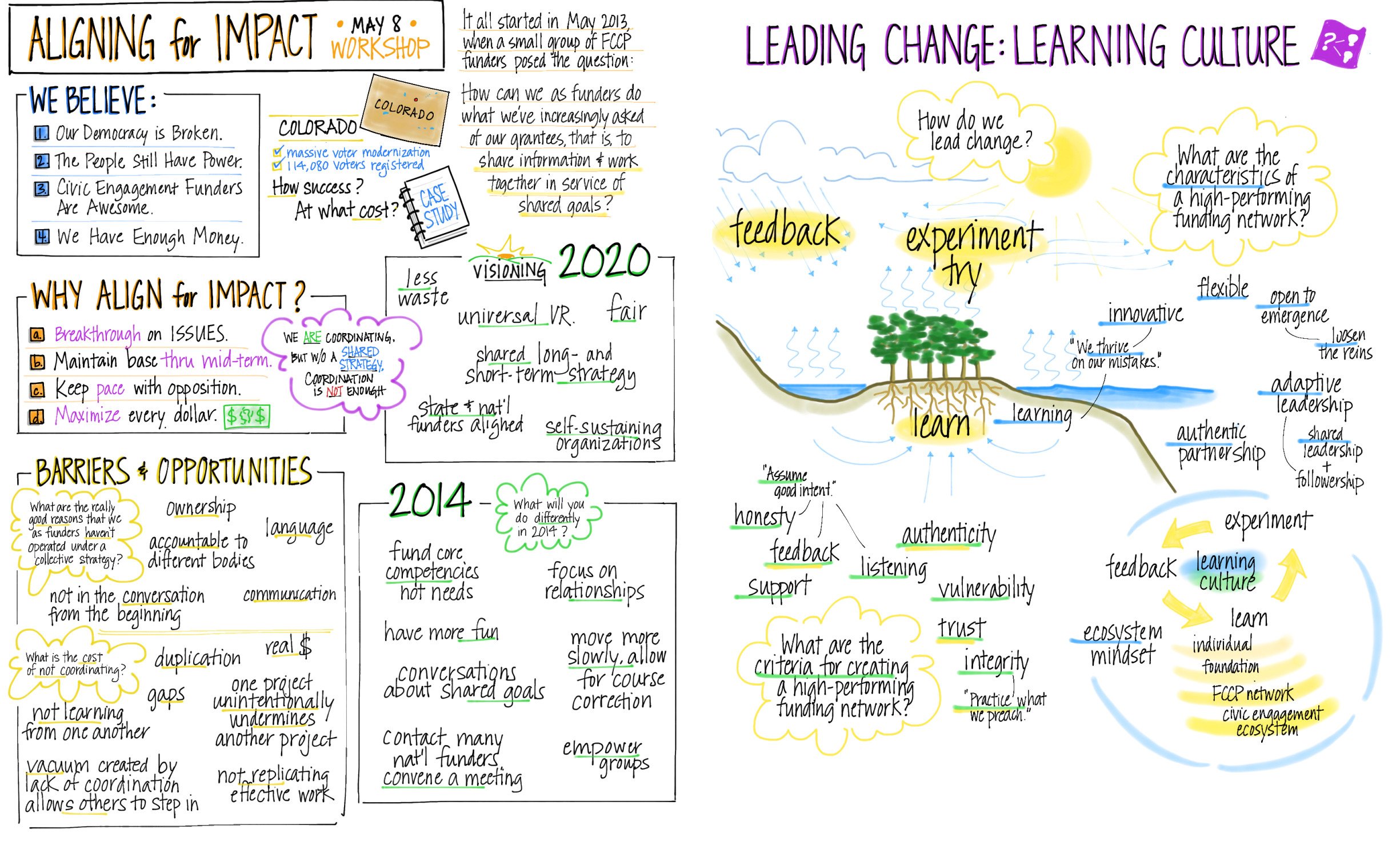

Toward the end of Phase 1 of the Delta Dialogues, we designed a whole day around the Squirm Test. We had participants capture on flipcharts what they thought the interests and concerns were of the other stakeholder groups. Then we had participants indicate whether these points represented themselves accurately and whether they found shared understanding on certain issues surprising. There was very little squirming and quite a bit of surprise about that fact. It was a turning point for the process, because the participants were able to see in a visceral way how much shared understanding had been built through all of their hard work together.

Last week, I was describing the Squirm Test to Rick Reed, the leader of Garfield Foundation’s Collaborative Networks initiative. He pointed out a discrepancy that I had not thought of before. “People might not be squirming because there’s no shared understanding. They might be squirming because, after seeing the collective understanding, they realize that they’re wrong!”

This is exactly what happened with the Garfield Foundation’s first Collaborative Network initiative, RE-AMP. When you are able to see the whole system, including your place in it, you may discover that your frame is wrong. The kind of squirming that Rick describes is the good kind. Understanding how to design for it is a topic for another day!