For the past 18 years, I have begun almost every introductory conversation about my work with the following questions:

- What was your best experience collaborating with others?

- What would your life be like if all of your collaborative experiences were at least as good as your best?

- What would the world be like if everyone's collaborative experiences were at least as good as their best?

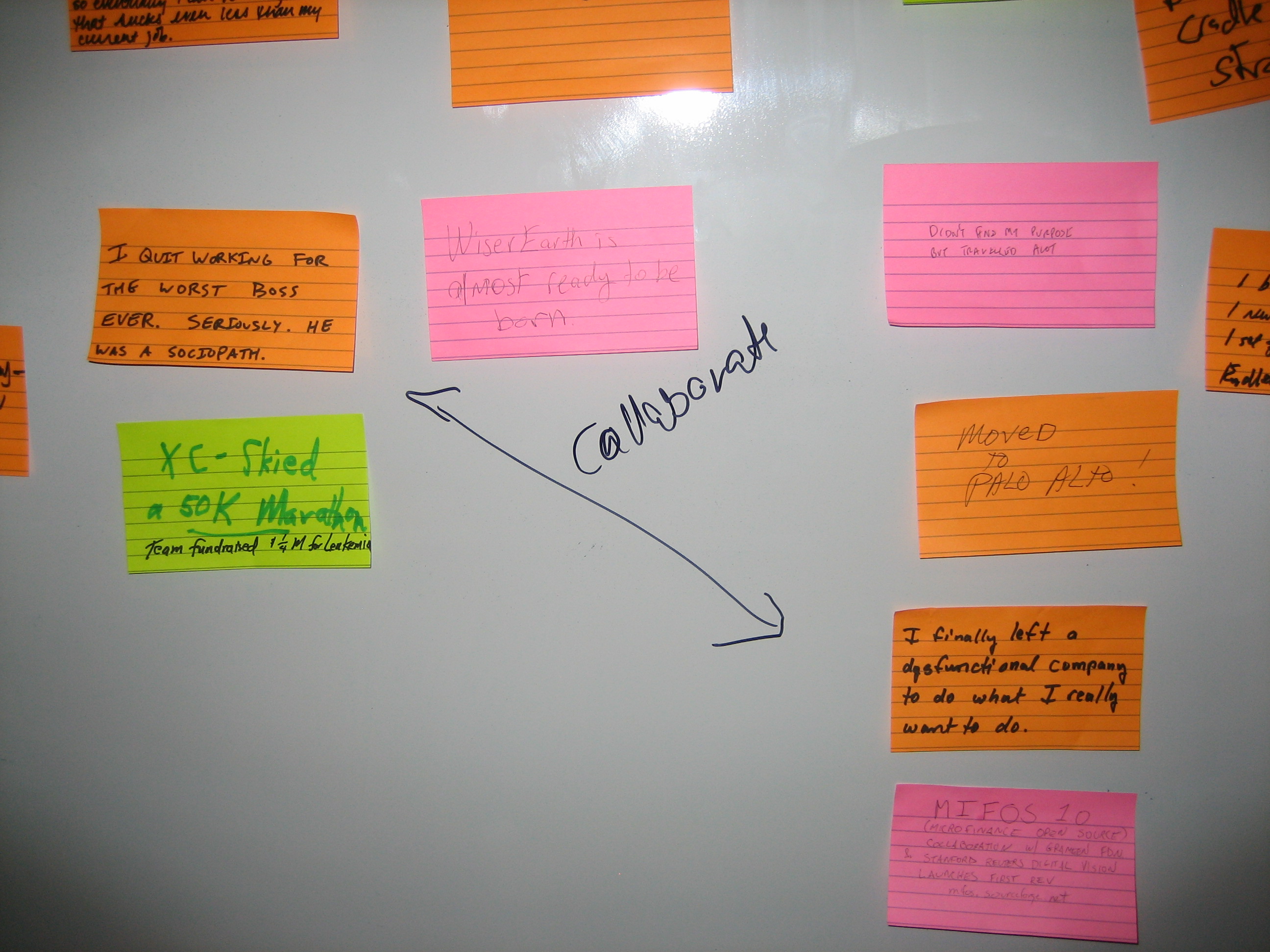

People’s reactions are fascinating. Some respond quickly with great stories. Most do not. Many seem to find it easier to think of stories from their personal rather than their professional lives. Everyone finds it easier to come up with terrible experiences than with great ones.

We all want to live in a world where our experiences working and being with others feel vibrant, productive, and meaningful, where we feel more capable and alive with others than we do by ourselves. I believe that this world is possible. It’s why I do what I do. Most people with whom I come across don't share this belief, and I can understand why. If it's so difficult to come up with one great experience collaborating with others and if most of your experiences collaborating with others are terrible, why would you believe in the collective potential of groups?

Belief. This is where the work has to start.

All the Bad Things

My friend and colleague, Travis Kriplean, had his first kid three years ago. As with many of my friends, impending parenthood caused him to reflect about the world he was bringing his son into and what he could do to make it better. As part of that, he began a deep inquiry into the impending planetary crisis we find ourselves in.

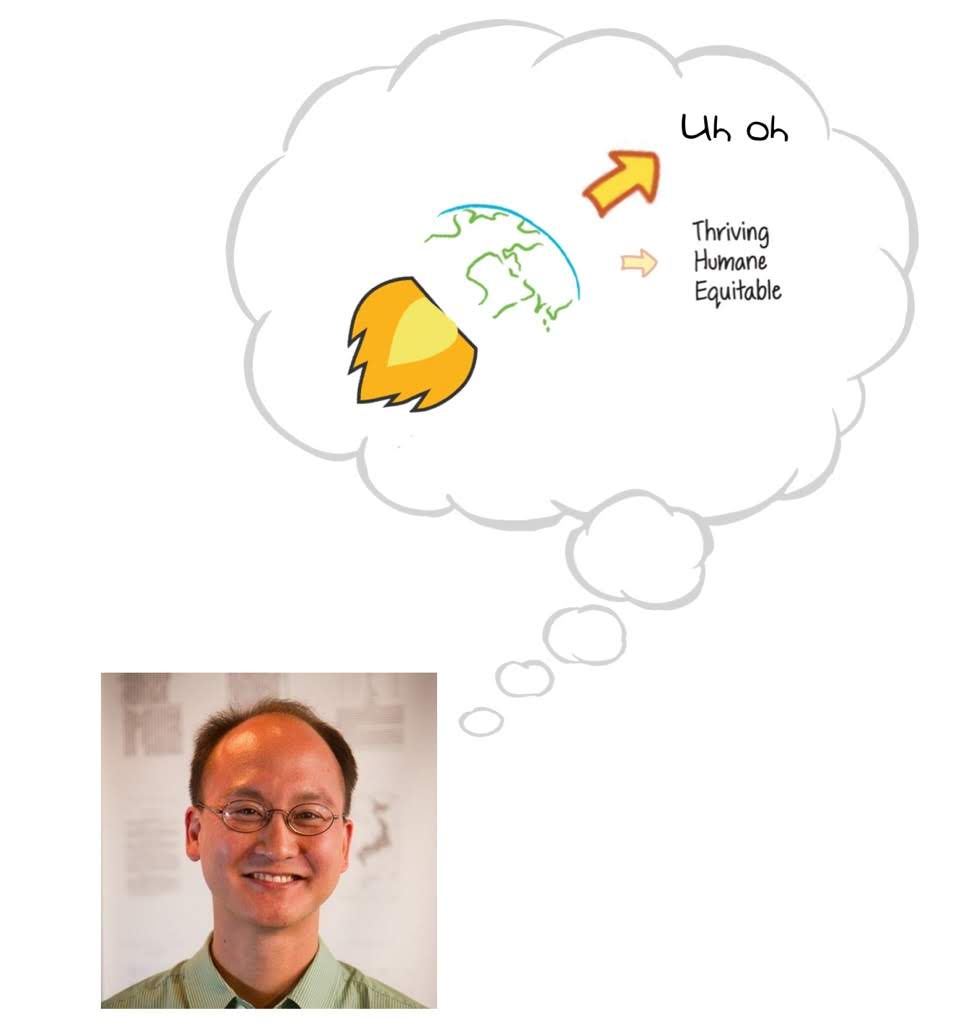

As Travis started to emerge from his inquiry, he pulled together a reading list and started organizing one-on-one discussions with friends, including me, to help him make sense of what he was learning. I read each of his carefully curated items over the course of a few weeks, then we talked for over two hours about the readings. I happened to be in the middle of my own little experiment around sensemaking, and as part of that, we both agreed to draw and share a picture that somehow represented what we had heard and felt from our conversation. The following day, Travis sent me his picture of our conversation. He had taken my vision image that’s on the homepage of this website and performed a cheeky (and accurate) cut-and-paste job:

As was clear from his reflection of our conversation, I had been completely demoralized by the readings and our conversation. The day after we talked, as if to punctuate the all-too-likely doomsday scenarios we had discussed, San Francisco became engulfed in a smoky haze from the Camp Fire, which ended up becoming the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California history. The filthy air enveloped us for two weeks, reminding me that blue skies and breathable air might soon become a thing of the past.

What made it worse was that I wasn’t exactly starting from a place of cheeriness to begin with. Watching intolerance, white supremacy, and isolationism become normalized, even celebrated, all over the world has been disheartening to someone whose mission for the past two decades has been to increase self-awareness and empathy, to encourage critical and systemic thinking, and to find healthier ways to lean on each other for the benefit of all.

For the past three years in particular, I’ve spent a lot of time wondering whether I’ve been doing the things I need to do to move the needle on the world I want to live in, or whether I’ve been fooling everyone, myself especially, peddling false hope, smoke, and mirrors. It’s been a tortuous process, and I’ve made many changes as a result.

Despite all of this, I still believe.

Forgetting

Twenty years ago, when I was in the gestation period that would put me on my current path, I learned something interesting about Benjamin Spock, the famed pediatrician and author of The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care, first published in 1946. For 50 years, Spock’s book was the number two best-seller in the world. (Number one? The Bible.)

I found this startling. How could this be? Humans have been around for thousands of years, and we’ve been parenting that whole time. We have a lot of practice and experience and wisdom to build on. Why would we suddenly seek validation and knowledge from this one person about something we’ve been doing for so long and that’s so inherent to whom we are? Was Spock so much more insightful than anyone else about parenting? Was he better at explaining parenting than anyone else? Had we collectively forgotten how to parent?

As a child of immigrants, I am acutely aware of how easy it is to collectively forget. Like many immigrant kids of my generation, my parents taught me and my sisters English first, because they didn’t want us to speak with accents and they didn’t realize that it was easier to learn multiple languages when you’re young. Like many immigrant kids of my generation, I never ended up learning to speak my parents' native tongue, Korean.

When I was 14, my family went to visit my grandfather in Korea. He had not seen me since I was three years old, and he didn’t realize that I couldn't speak his language. As soon as we arrived, he asked me to come into his room to speak with me privately. He then started asking me questions in Korean. I felt disoriented and ashamed as I tried to explain to him in English that I didn’t understand him and as I watched his face shift from confusion to deep disappointment.

I never got another chance to speak to my grandfather, as he passed away the following year. It wouldn’t have mattered. I still can’t speak Korean, which means that I can’t speak to most of my relatives, I can’t read through old family letters and documents, and that so much of my family’s history and tacit knowledge will end with me.

It takes just one generation to forget, and the conditions for forgetting keep getting more optimal. Over the past century, families have separated and gotten smaller. Civic and community engagement have deteriorated (as Robert Putnam documented in his 2000 book, Bowling Alone), seemingly replaced in this day and age by clicks and swipes.

There was a time when we, as human beings, understood what it meant to thrive together, both in work and in play. We passed along the know-how and the rituals for generations. Now, it seems like we’re starting to forget. As our memories of what it means to be and thrive together wane, so does our faith.

On the one hand, the timing couldn’t be worse. On the other hand, maybe the popularity of Spock's work is simultaneously a sign of remembering as well as forgetting.

Remembering

In 1949, three years after Spock first published his book on parenting, the philosopher, Martin Heidegger, delivered a lecture entitled, "The Question Concerning Technology." In it, he argued that the essence of modern (i.e. post-Industrial Revolution) technology was to make us see everything — including each other — as things to be exploited and manipulated. Seeing and engaging in the world in this way resulted in us forgetting our humanity.

It’s a bleak essay, especially in the context of these times, but Heidegger does offer one tiny glimmer of hope. Toward the end of his lecture, he quotes the poet, Friedrich Hölderlin:

But where danger is, grows

The saving power also.

He then argues that the act of losing your humanity also makes you remember it, maybe even value it more. This awakening is a necessary (but not sufficient) first step in taking back what you’ve lost.

Heidegger’s framing of technology and humanity resonates with me on many levels. I think of it often when I think about my mentor, Doug Engelbart, who is the reason I'm in this business. Doug is most remembered for the long list of technology that he and his lab invented in the 1960s, including the mouse, graphical user interfaces, and hypertext. But Doug was never about inventing things. He was about lifting people up, about addressing the challenges that we were about to face, about augmenting our collective intelligence.

It took me a while to understand how radical and threatening these ideas were at the time. Most of the research in computer science in the 1950s and 1960s was focused on automating intelligence, replicating, even replacing humans, further validation of Heidegger's critique of modern technology. Doug was ridiculed, even reviled, but he was stubborn, and he was fortunate to have some visionary support in high places.

When I first met him in the late 1990s, it seemed like there was a large-scale awakening in society that had started happening, an appreciation of Doug's centering of people, which still felt radical, although perhaps no longer reviled. Still, he was scarred from those early experiences, and he continued to be troubled and depressed by how few people took his dire warnings about the future seriously. He passed in 2013, and I can't imagine how he'd be feeling if he were alive today.

Doug's commitment to his enormous vision was powerful, but that was not what ultimately had the most profound impact on me. What affected me most was how he treated me.

From the very beginning until the very end, he was curious about me, and he valued and cared about what he saw. When we first met, I was in my early 20s and hadn't accomplished anything of significance. None of that ever mattered to Doug. He treated me like a peer, and he cared about all aspects of me as a human being. I spent a lot of time wondering why he treated me so well and why he was so generous with me, before finally understanding that he treated everyone this way.

Imagine that. Doug treated everybody well, like they mattered, simply because they were fellow human beings. This impacted me more than any of his brilliant ideas, it's why I do what I do, and it's why I still believe. It seems so ridiculously simple and obvious, but I believe we've collectively forgotten how important it is, and more importantly, we're out of practice. If we start here, we have a chance. But we can't skip this step, because without it, we won’t remember how good it can be to be with others.

Practice, Hope, and the Trickle-Up Effect

Over the past few years, I’ve had the privilege of working with Sarita Gupta, who is not only a brilliant leader and organizer, but who also treats people the way Doug did. Before transitioning into her role at the Ford Foundation late last year, Sarita was the long-time leader of Jobs With Justice and Caring Across Generations, and had spent her entire career focused on the well-being of workers around the world. I spent a good amount of time with her and other progressive leaders trying to understand and help synthesize their visions and theories of change, so that they could see and explore where they were aligned.

Here’s what Sarita explained: Living with each other harmoniously, productively, and equitably at a national (or larger) scale doesn’t just happen, even when there’s structural support (which, for many people, there’s not). It requires lots and lots of practice to do it right. Trying to practice at a national scale is hard, perhaps impossible. However, it becomes viable and is just as valuable when we try it at a much smaller scale — with families, friends, community groups, schools, unions, the workplace, and so forth. When enough of us are leveraging these smaller spaces to practice, then we start to build collective power, a natural trickle-up effect starts to happen, and things start improving at a larger scale too.

Said another way, if we want to thrive collectively at a large scale, we need to start by learning how to thrive collectively at very small scales. When we ask each other, “What’s the best experience you’ve ever had collaborating with others?”, we need to be able to easily come up with stories. If we can do this, we will remember and believe. In these exceptionally challenging times, it’s hard to imagine anyone truly believing in democracy otherwise.

I already shared Sarita’s beliefs around the importance of practice and building “muscle,” but her overall framing has given me greater clarity and resolve around my own strategic focus. Specifically, we can have the impact we want on the larger world if we all start small, if we focused on spaces and groups in which we already have agency.

We can start with this simple principle, which Doug and Sarita modeled so well: Treat everybody well, like they matter, simply because they are fellow human beings.

When we invest in our personal relationships, we are building collaboration muscles necessary for a stronger democracy. When we invest in our own teams and organizations so that they have exceptional cultures where everybody brings their best and feel valued, we are building collaboration muscles necessary for a stronger democracy.

As we start to experience vibrant, productive, and meaningful relationships in small spaces, we will start to remember how powerful and wonderful it is to engage with each other collectively, which will inspire us to flex our collaboration muscles in all aspects of our lives. The more of us who start to do this, the more we will start to see larger-scale shifts.

This is how we will remember. This is how we will believe.

This is why I do what I do. This is why, despite all of the challenges we face today, I still believe.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS