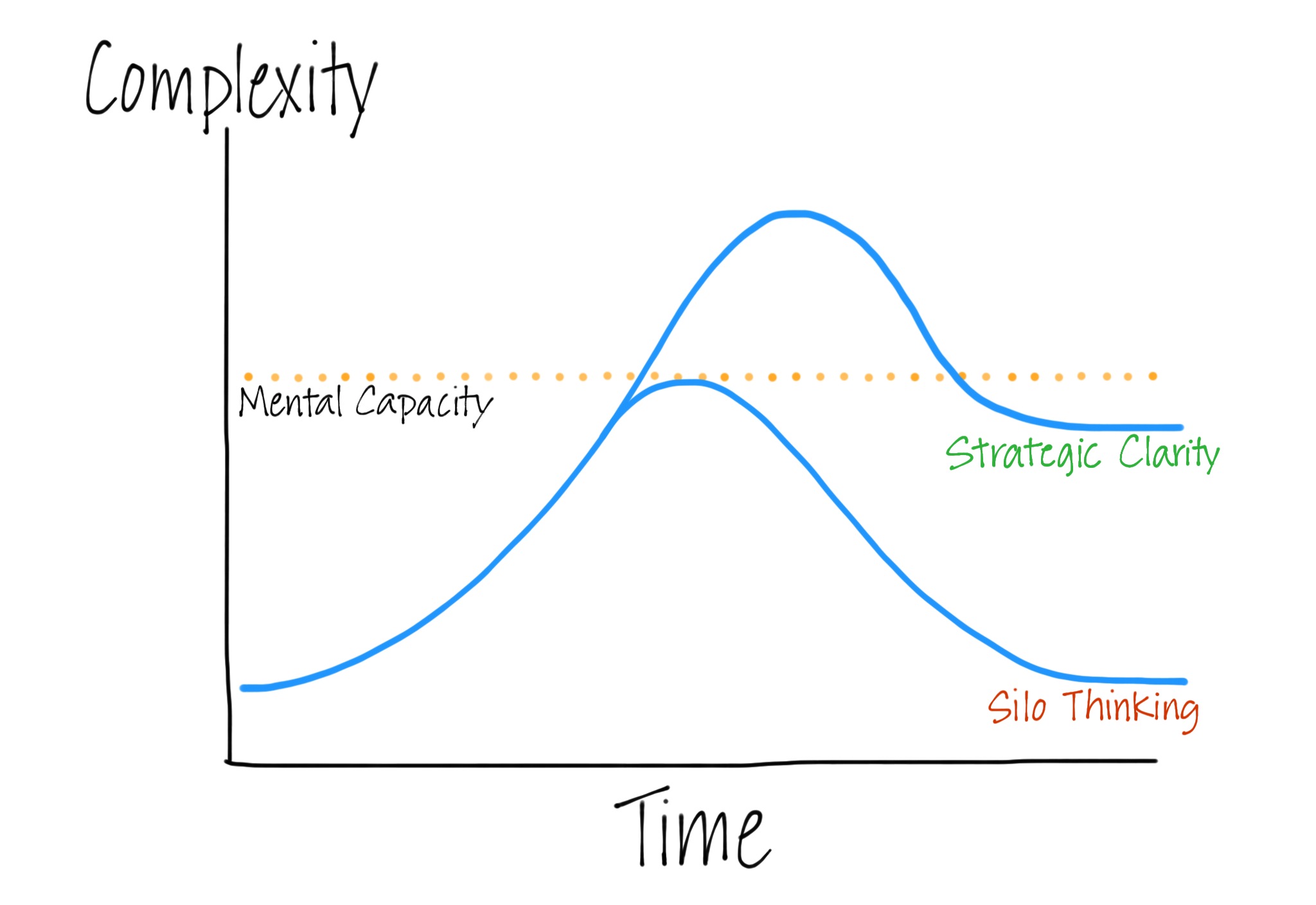

One of the signature tools that the Garfield Foundation advocates for in its collaborative networks projects is system mapping. System mapping is a way of visually capturing the things that influence a system and their relationships to each other. Doing this can lead to insights about high-leverage ways to shift the system, which in turn can help groups act more strategically.

That’s the theory, at least, and it’s one that’s widely espoused. But it’s also vastly oversimplified with some problematic assumptions.

The first assumption is that people can make sense of these maps in the first place. It doesn’t take long before a map becomes challenging to understand. One of the best maps I’ve seen is the one that emerged from the Hawaii Quality of Life project.

This map was constructed skillfully and thoughtfully and is easily browsable thanks to the wonderful tool, Kumu. But it still takes some time to wrap your head around it, and most system maps are significantly harder to understand than this one.

The second assumption is that the map represents a good model of reality. This depends on your definition of “good.” The quality of the map depends on its sources. How do you know if those sources are correct? Furthermore, in complex systems, nuances are critical, because small shifts can lead to big changes. How do you know if your model has captured the “right” nuances?

My friend and mentor, Jeff Conklin, likes to say, “All models are wrong. But that doesn’t mean they can’t be useful.” System mapping is a wonderful way of building shared understanding and trust. If I see my worldview represented in a system map, and if that map is used in my conversation with other stakeholders, I can see that others are truly listening to me and vice-versa. We can see our (sometimes surprising) common ground, and we can better understand our differences. That leads to higher-quality strategy and collaboration.

Reframing the mapping this way helps route around these problematic assumptions while also placing greater importance on how the maps get constructed and how they are used. If participants play an active role in constructing the map, they will better understand it and feel greater ownership over it. If they see it as a tool for understanding each other, they are less likely to be led astray by the false gods of rigor. If they understand the inherent limitations of the model, they are more likely to treat potential strategies as hypotheses to be explored rather than hard truths to be followed at all costs.

The third assumption is that people will be able to change their minds once they see and agree on a map of the system. This is the most challenging assumption of all, because it assumes that we are rational, which we are not.

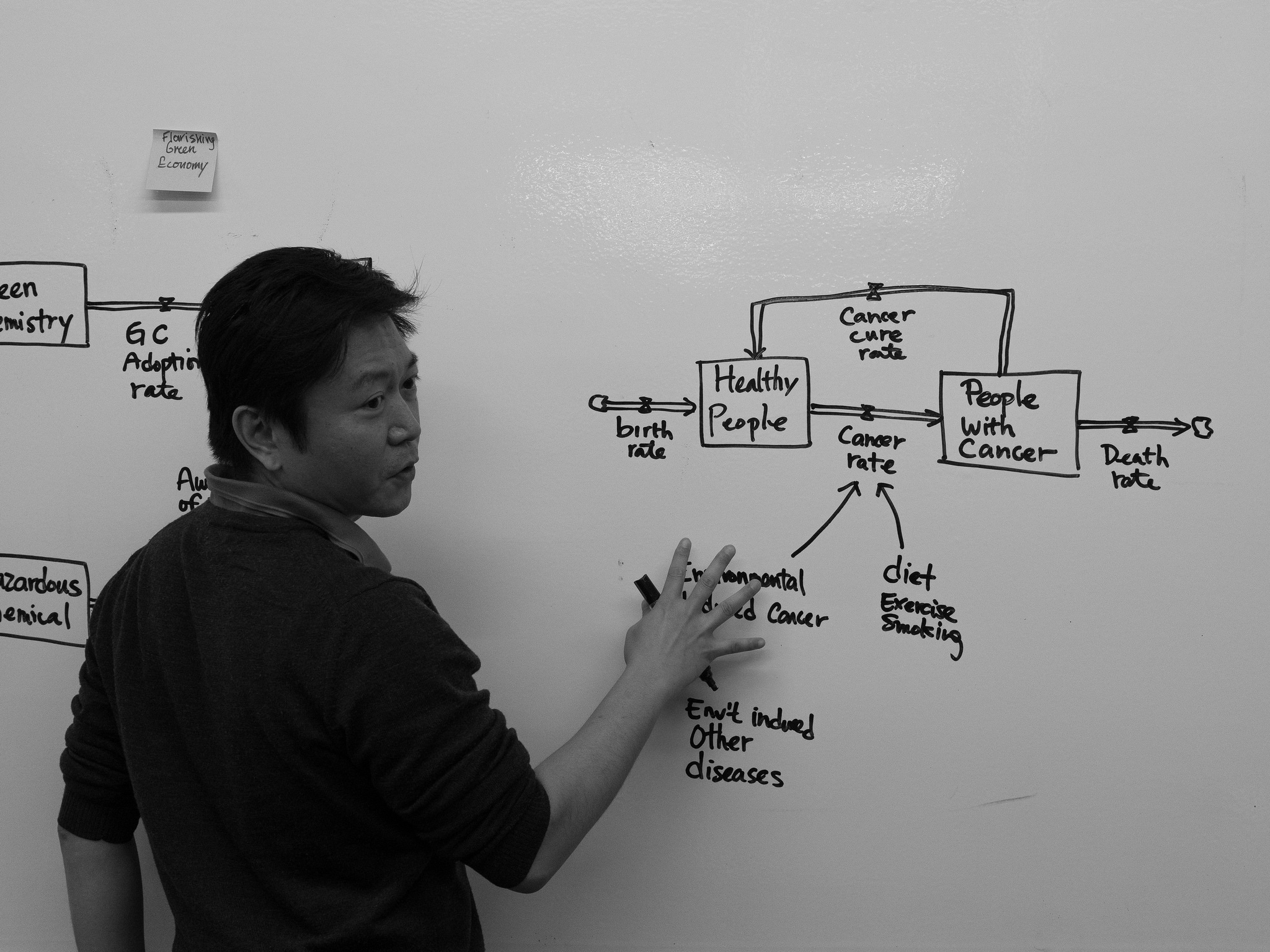

Our system mapper, Joe Hsueh, recently wrote a wonderful post, “Why the human touch is key to unlocking systems change,” where he explained the critical importance of starting with self before looking at others.

Systems change with multi-stakeholder groups in a complex system is very hard. People get stuck in their respective positions and entrenched interests, refusing to be told they are the ones need to change. One simple phenomenon about change – we like to change others, but none of us like to be changed. Just think about the ones closest to us – our spouses, children, parents – how often are we truly successful in changing others?

In my year volunteering at a Buddhist monastery and charity organization, I learned I cannot change people. What I can do is to cultivate my curiosity to see a person for who she is and the compassion to love her as much as I can. Seeing a person for who she is the first act of love. When I am being seen for whom I am without judgment, it opens up a space for me to see myself authentically and give me the self awareness and choice to be my best Self.

Similarily, through our work on systems change at the Academy for Systemic Change, Presencing Institute and SecondMuse, we found the highest leverage is not out there but in here. “What is most systemic is most personal,” is a quote I love from Peter. How can we co-create a space for us to be human, to see each other for who we are as human beings, and to inspire one another to our best possible Selves? Only when we see each other and feel being seen can we begin to inquire the possibility of a shared vision that connects us as human.

You don’t find many system mappers citing the importance of the L-word — love — but love is at the heart of systems change, as our facilitator, Curtis Ogden, recently explained in a beautiful post.

Sometimes the L-word is explicitly acknowledged, sometimes it’s not, but it is always present in stories of deep systems change. In the late 1990s, the groundbreaking Public Conversations Project quietly began convening a dialogue between leaders of both sides of the abortion debate. They spent six years in deep conversation and were not able to find common ground on the issues. What they did find was that they loved each other more. They wrote:

In these and all of our discussions of differences, we strained to reach those on the other side who could not accept – or at times comprehend – our beliefs. We challenged each other to dig deeply, defining exactly what we believe, why we believe it, and what we still do not understand.

These conversations revealed a deep divide. We saw that our differences on abortion reflect two world views that are irreconcilable.

If this is true, then why do we continue to meet?

First, because when we face our opponent, we see her dignity and goodness. Embracing this apparent contradiction stretches us spiritually. We’ve experienced something radical and life-altering that we describe in nonpolitical terms: ”the mystery of love,” ”holy ground,” or simply, ”mysterious.”

We continue because we are stretched intellectually, as well. This has been a rare opportunity to engage in sustained, candid conversations about serious moral disagreements. It has made our thinking sharper and our language more precise.

We hope, too, that we have become wiser and more effective leaders. We are more knowledgeable about our political opponents. We have learned to avoid being overreactive and disparaging to the other side and to focus instead on affirming our respective causes.

Since that first fear-filled meeting, we have experienced a paradox. While learning to treat each other with dignity and respect, we all have become firmer in our views about abortion.

We hope this account of our experience will encourage people everywhere to consider engaging in dialogues about abortion and other protracted disputes. In this world of polarizing conflicts, we have glimpsed a new possibility: a way in which people can disagree frankly and passionately, become clearer in heart and mind about their activism, and, at the same time, contribute to a more civil and compassionate society.

I believe strongly in the value of good, reality-informed strategic thinking. I have no doubts that a mapping process would have improved the Public Conversations Project discourse. However, I also don’t think it would have changed the final outcome. What mattered most there was that people were engaging with each other deeply and authentically. They were learning to appreciate each other’s humanity.

Any effective systems change process — whether or not you are using mapping to support it — is ultimately about helping us understand and love each other. What role is the L-word playing in your systems change process?