One of my favorite sayings is, “Chefs, not recipes.” It’s a phrase that I stole from Dave Snowden, and it perfectly encapsulates the approach I think we need to take (and aren’t) in the collaboration, networks, and organizational development space. I believe in this so strongly that I had it engraved on the back of my phone.

What exactly does this mean, and why do I find it so important?

One of the reasons I got into this field was that, over a dozen years ago, I experienced exceptional collaboration in open source software development communities, and I wondered whether similar things were happening in other places. If they were, I wanted to learn about them. If they weren’t, I wanted to share what I knew. I thought that developing shared language around common patterns could help groups achieve high-performance.

I still believe that a good pattern language would be useful, and there’s been some interesting movement in this direction — particularly Group Works and Liberating Structures. (Hat tip to Nancy White for pushing me to explore the latter.) However, I think that there’s a much bigger problem that needs to be addressed before a pattern language can become truly useful.

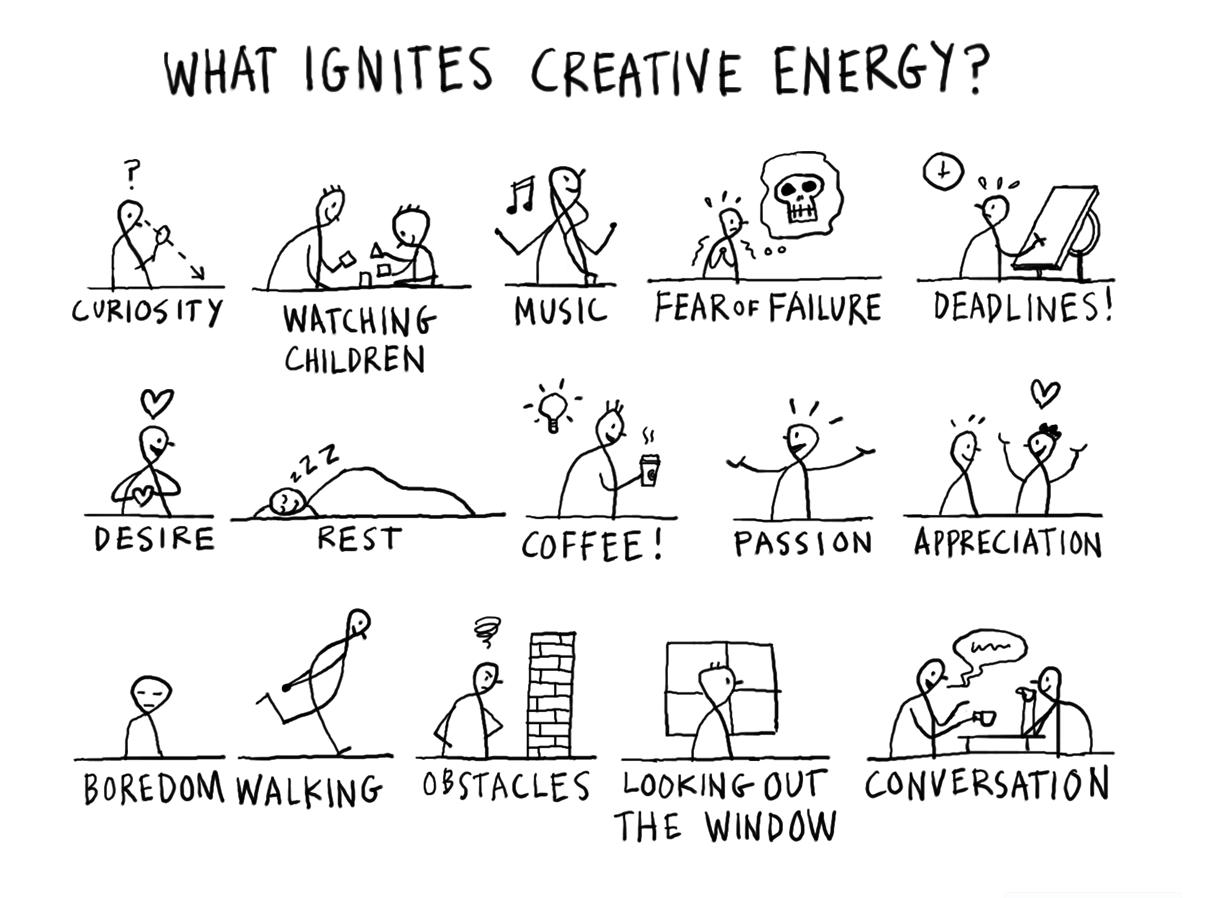

Collaborating effectively is craft, not science. There are common patterns underlying any successful collaboration, but there is no one way to do it well. It is too context-dependent, and there are too many variables. Even if best practices might be applicable in other contexts, most of us do not have the literacy to implement or adapt them effectively. We think we lack knowledge or tools, but what we actually lack is practice.

I’m a pretty good cook, but I still remember what it was like to be bad at it. I first tried my hand at cooking in college, and I was so intimidated, even simple recipes like “boil pasta, add jarred sauce” flummoxed me. I was so incompetent, a friend mailed me a box of Rice-A-Roni all the way from the other side of the country because she was afraid I would starve.

Back then, I followed recipes to the letter. I had no way of evaluating whether a recipe was good or bad, and if it turned out badly, I didn’t know how to make adjustments. I ended up defaulting to the same few dishes over and over again, which meant that I got better quickly, but I also plateaued quickly.

A few things got me over the hump. I had lots of friends who cooked well. I relied on them for guidance, and I especially enjoyed cooking with them, which allowed me to see them in action and also get feedback. But the turning point for me was challenging two of my less experienced friends to an omelette competition. (I suppose that speaks to another thing that helped, which was that I was brash even in the face of my incompetence.)

I cooked omelettes the way my parents cooked them and the way I assumed everyone else cooked them. But both of my friends cooked them differently, and I liked all three versions. The differences in approaches were more subtle than what was usually captured in a recipe, but the differences in results were clear.

That experience made me curious about my assumptions. Most importantly, it got me asking “why.” Why do things a certain way? What would happen if I did it differently? I also stopped using recipes, choosing instead to watch lots of cooking shows, cook with others (including people who worked in kitchens or were professionally trained), and experiment on my own. Recipes were a helpful starting point, but they were not helpful beyond that. While better knives and pans improved my ability to execute, they did not make me a better cook.

Recipes and tools have their place, but they are relatively meaningless without the literacy to wield and interpret them. Practice, experimentation, mentorship, constantly asking “why” — these are the keys to mastering any craft. This was my experience learning how to cook, and it’s also been my experience learning how to design and facilitate collaborative engagements.

What does approaching collaborative work as a chef as opposed to a set of recipes look like? It starts with asking “why” about everything. For example, if you’re designing and facilitating a face-to-face meeting:

- What are your goals, and why?

- How are you framing them to participants, and why?

- How are you arranging your space, and why?

- When are you breaking up your group, and why (or why not)?

- What kind of markers are you using, and why?

- Why are you having a face-to-face meeting at all?

I meet a remarkable number of practitioners — even ones with lots of experience — who can’t answer these questions. They’re simply following recipes.

Even if you have answers to all of these questions, don’t assume that your answers are the best ones. Experiment and explore constantly. Shadow other practitioners, especially those who approach their work differently. Intentionally do the opposite of what you might normally do as a way of testing your assumptions.

Finally, if you are a more experienced practitioner, remember that in professional kitchens, chefs have a supporting cast — sous chefs, line cooks, prep cooks, and so forth. If you yourself are not regularly working with a team, you’re not optimizing your impact. Most importantly, find a way to mentor others. Not only is it a gratifying experience, you’ll find that the learning goes both ways.

Photo by yassan-yukky. CC BY-NC.