When I was in my early 20s, I used to play pickup basketball with a guy who was 20 years older than me, but didn’t look it. He was in superb shape, and he never seemed to get injured. At one of our games, I sprained my ankle, and when I was healthy enough to return, I asked him if he had any rehab tips. "Yoga," he replied. He hadn't sprained his ankle in over ten years, which he attributed to his yoga practice.

I was intrigued, but never seemed to get around to trying it. It took me another ten years before I took my first yoga class. It was hard, it felt great, and I could see the value of making it a regular practice. But I never did, and I was totally okay with that.

Now I’m in my mid-40s. My partner is an avid yoga practitioner, so I’ve been doing it more often too — at least once a month. As someone who likes to push myself, I used to chuckle when my instructors would encourage us to do the opposite, to appreciate where we were and to celebrate that we were doing something rather than strain to do more and possibly hurt ourselves along the way. It was the opposite of how I was used to doing things, but I ended up embracing this kinder, gentler mentality. Frankly, if this weren’t the culture, I would probably never do yoga at all. Which is the point!

Here’s the thing. The last few years, I’ve done yoga more than I ever have, but I’m not noticeably stronger or more flexible. In fact, I’m pretty sure I’m less flexible. The yoga has almost certainly slowed my deterioration, and it’s undoubtedly had other positive effects as well. However, if I want to counter or even surpass the impact of age and lifestyle, once a month clearly won’t cut it.

High-performance is a choice. It’s okay not to make that choice (as I have with yoga and my overall flexibility), but it’s helpful to be honest with yourself about it. If you’re the leader of a group, it’s not just helpful, it’s critical, because saying one thing and behaving differently can end up harming others, even if your original intentions were sincere. I have seen this play out with groups my entire career, and I’m seeing it play out again in this current moment as groups struggle with their desire to address their internal challenges around racial and gender equity.

The root of the problem is lack of clarity and alignment around what success looks like. A good indicator of this is when leaders say their groups should be doing “more,” without ever specifying how much. What do you actually mean by “more”? If you have a yoga view of the world, then “more” might imply that whatever you end up doing is fine, but not necessary. You’re not holding your group or yourself accountable to the results. If this is indeed what you mean, then it’s better to make this clear. (With the Goals + Success Spectrum, you can do this by putting it in the Epic column.)

If this isn’t what you mean, then you run the risk of doing harm. People project what “more” means to them, which leads to contradictory expectations, working at cross-purposes, and toxicity. Worse, people’s definitions can shift over time. When this happens, the person with the most power gets to decide whether or not the group is succeeding or failing, and ends up doling out the consequences accordingly.

A team can’t perform if the target is obscure and constantly moving. Furthermore, if someone is already being marginalized in a group, a system like this is only going to further marginalize them. It’s also natural to question a group or leader’s sincerity when they aren’t holding themselves accountable to clear goals.

Instead of saying “more,” groups and leaders should practice asking, “how much?” How much more revenue are you trying to make? How much more equitable are you trying to be? How much more collaborative are you trying to be? What exactly does success look like to you? Most importantly, why? Why is it important to make this much more revenue, or to get this much more equitable or collaborative?

Your answers to these questions will help you understand whether or not your strategies and even your goal make sense. If your goal is to stay in shape, then running a few miles a week might be enough. If your goal is to run a marathon, then running a few miles a week isn’t going to get you there. If you don’t want to run more, maybe it’s better to prioritize staying in shape over running a marathon.

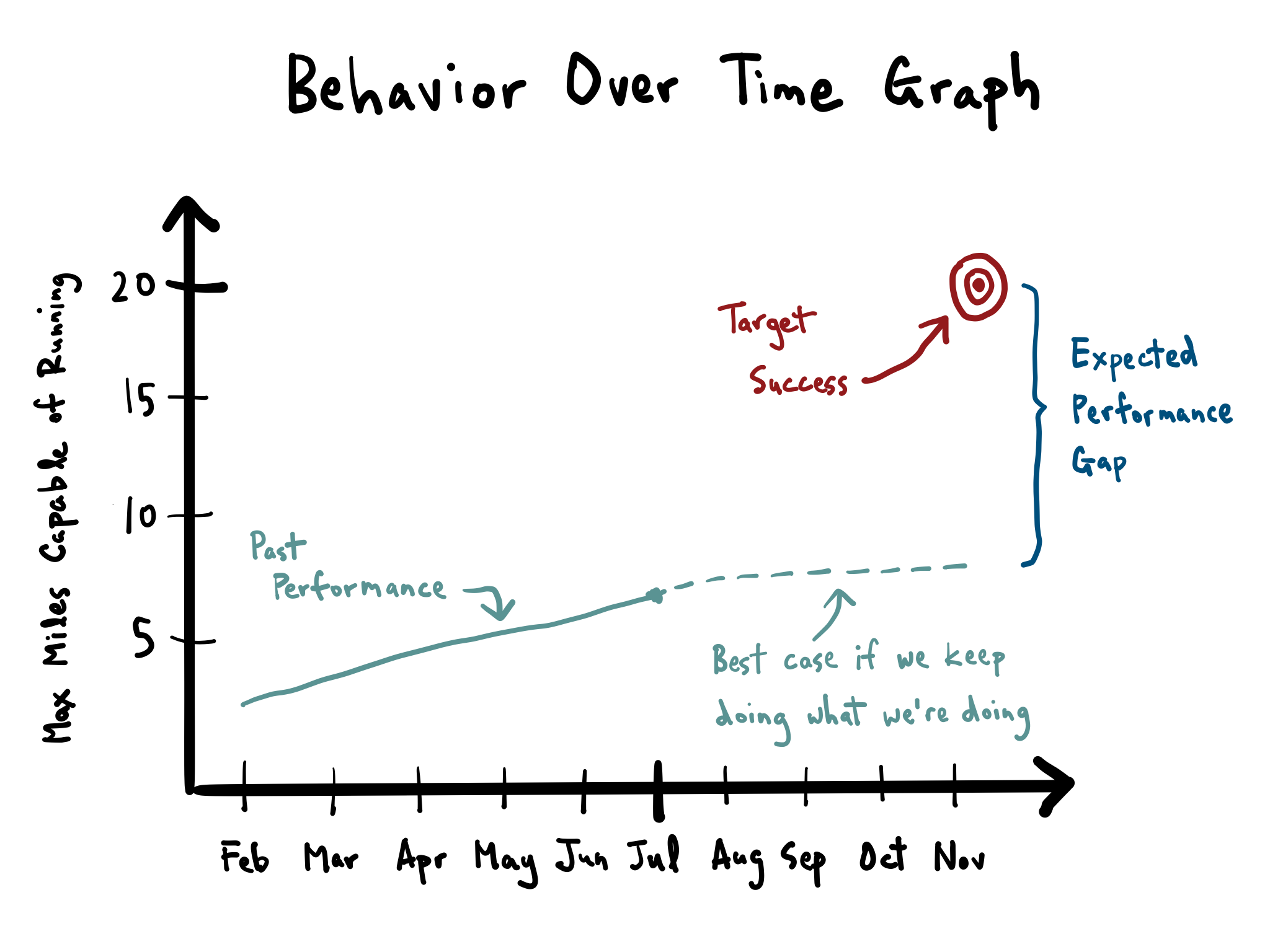

One of my favorite tools to use with groups is the Behavior Over Time graph. Once a group has articulated what “how much” success looks like, I ask them to draw a graph, where the X-axis is time and the Y-axis is the success indicator you’re tracking. I then ask them to put the current date in the middle of the X-axis and to graph their historical progress. Finally, I ask them to graph their best case scenario for what the future might look like if they continue doing what they’re doing.

For example, if my goal is to run a marathon by November, but I’m only running a few miles a week, my Behavior Over Time graph might look like this:

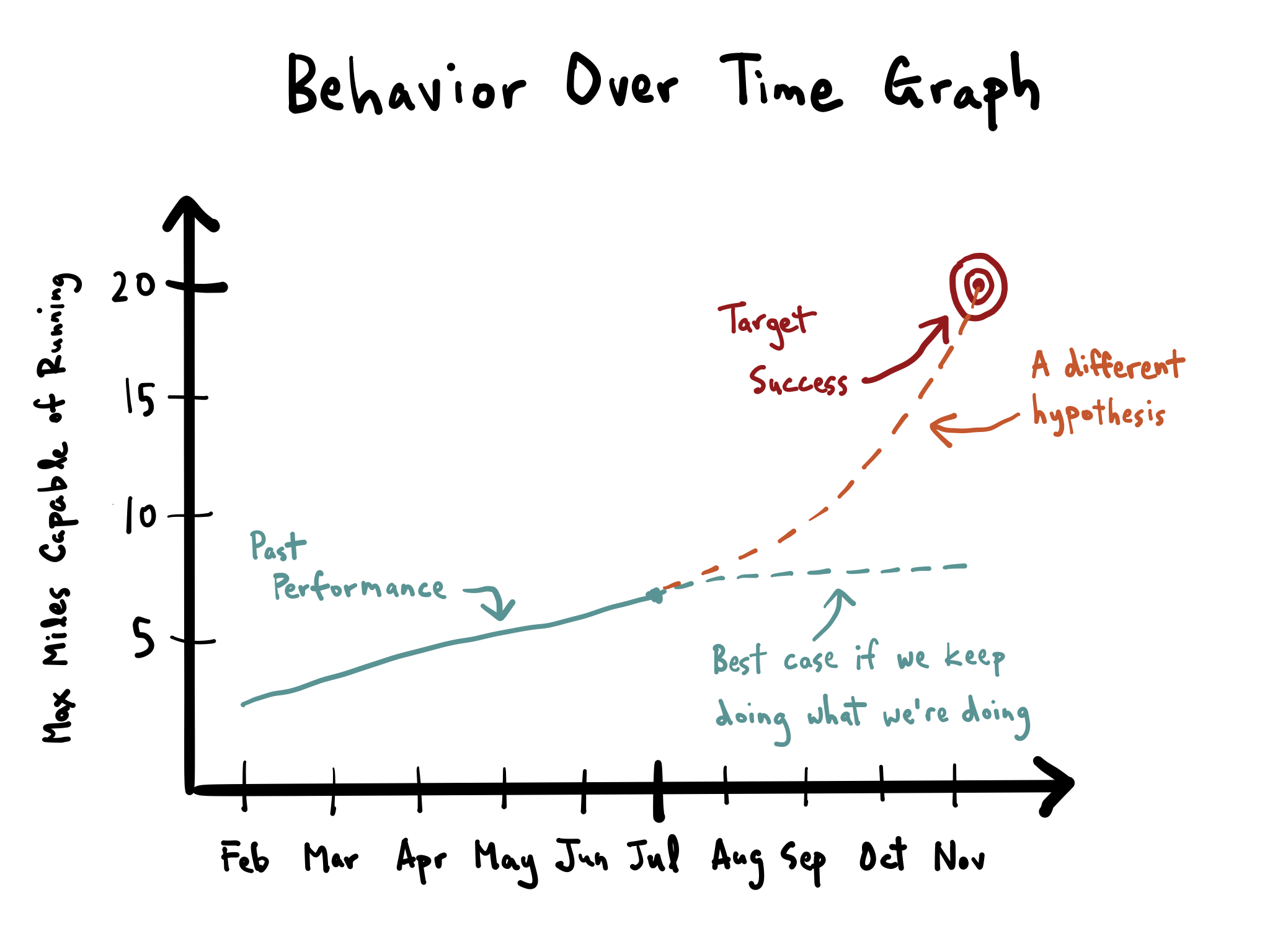

The gap between the best case scenario and where I want to be is a signal that I either need to do something differently or change my goal. However, someone else might have a different hypothesis for what the best case scenario is:

The goal of all this is not to rigidly quantify everything, nor is it to analyze your way to a “definitive” answer. The goal is to make your mental models and theories of change explicit, so that you and others can talk about them, align around them, test them, and either hold yourself accountable or openly and collectively adjust your goals as you learn.

Getting concrete about “how much” is a lot harder than simply saying, “more.” You might think you can do everyone a favor by keeping things ambiguous, but what you’d actually be doing is exacerbating toxic power dynamics, where everyone is left guessing what the goal actually is and starts operating accordingly.

The way around this is to do the hard work while applying the yoga principle of self-compassion. When you don’t achieve a goal, I think most of our defaults is to be hard on ourselves. The challenge and the opportunity is to re-frame success so that it’s not just about the goal, but about both the goal and the process. If you’re doing anything hard or uncertain, failure is inevitable. What matters is that you fail enough so that you have the opportunity to find success. Holding ourselves accountable to goals is important, but celebrating our hard work and stumbles along the way is equally so.

Photo by Eun-Joung Lee.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS