The “Secret” to High-Performance Collaboration Is Practice

On March 22, 2017, I had the pleasure of giving the keynote at The Collaboratory 5, a forum of about 200 Jewish innovators and entrepreneurs focused on grassroots change. My talk was on my favorite topic and the driving force behind my work for the past four years: how practice can lead to better collaboration.

Afterward, I led the whole group through the one-minute drill, followed by two breakout sessions where I led smaller groups through a power workout (including power video analysis and playing with status). My goal was not only to tell people how important practice was, but to lead them through an experience where they could get a sense of what I meant by practice and its value, especially if repeated over and over again.

I had an incredible time. It reminded me how different this mindset around practice is and how much I enjoy talking about and doing this stuff with new audiences. I’m looking forward to giving more talks and workouts in the near future. (If you’d like me to do this with your group, drop me an email.) Many thanks to my friend and colleague, Adene Sacks, for referring me and to Lisa Lepson, Jenny Kibrit Smith, and all of the organizers for inviting me and for being great hosts! Thanks to Duane Stork for the photo above.

Here’s a video of my talk!

Edited Transcript

Here are my slides and a tightly edited transcript.

What’s the best collaborative experience you’ve ever had? It could be personal or professional, with one other person or a large group, etc.

How many of you were able to come up with an example?

How many of you came up with one easily?

The story I want to share today has nothing to do with my work and didn’t even involve me. I have a friend who used to teach violin. She would start her beginning students by teaching them variations of Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star. The first time I saw her teach, she was teaching this very serious five-year old. Toward the end of the lesson, after numerous repetitions, my friend — who was playing alongside her student — decided to harmonize the last few bars. When she heard the harmony, the little girl’s face just absolutely lit up.

I’m lucky to have been a part of and to have seen and studied many great collaborative experiences. But that time I watched that little girl’s face light up upon experiencing that simple little harmony that she herself was a part of stands out in my mind. I get chills thinking about that moment, because hearing that simple little harmony lit me up too.

When I ask folks about their best experiences collaborating, most people have a hard time coming up with an example. But, whether you can easily recall an experience or not, I think everyone has had a moment like that little girl had with Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star. We all have an intuition about what great collaboration should feel like, even if we have low expectations about getting to experience it.

What would your world be like if all of your experiences collaborating were at least as good as your best?

What would the world be like if everybody’s experiences collaborating were at least as good as their best? Imagine this world for a moment, and soak in the feeling.

Practice

My mission for the past 15 years has been to create a world where everyone’s baseline experience with collaboration feels exactly like that little girl did when my friend started harmonizing with her.

How do you do this? How do you help improve everybody’s collaborative experiences?

Said another way, what’s the secret to high-performance collaboration, and how do you scale this?

About five years ago, I realized that most of my successes in helping others collaborate more effectively were hollow. We would do good work together side-by-side, we would achieve good outcomes, and people would have a good experience getting there. But when I left, most groups would fall back on old habits. I was like a ringer in basketball. If I played on your team, I could help make everyone better, but once I left, the team would revert back to what it was. Maybe folks picked up a thing or two along the way, but the impact wouldn’t be what I wanted it to be.

So I decided to rethink how I did the work. To help me do this, I started with the premise that collaboration is very hard to do well. If it weren’t, we’d all be doing it already, and it would be simple for everyone to come up with examples of great collaboration.

Then I thought about what it takes to achieve things that are very hard. I thought about things like playing the violin or learning a language (my personal bane). And my conclusion was simple.

The more you practice, the better you will get at collaboration.

Things that are hard require lots and lots of practice to do well. Everyone is capable of doing them better. You either put in the time, or you don’t. And if you don’t, you generally aren’t going to be successful.

Simple, right? Maybe so, but to me, this was a revelation. I realized that everybody I ever knew or saw — myself included —who was good at collaboration had had lots of opportunities to practice, whether it was conscious or not.

How much practice do we need to get really good at collaboration?

Consider one example of high-performance collaboration: professional basketball.

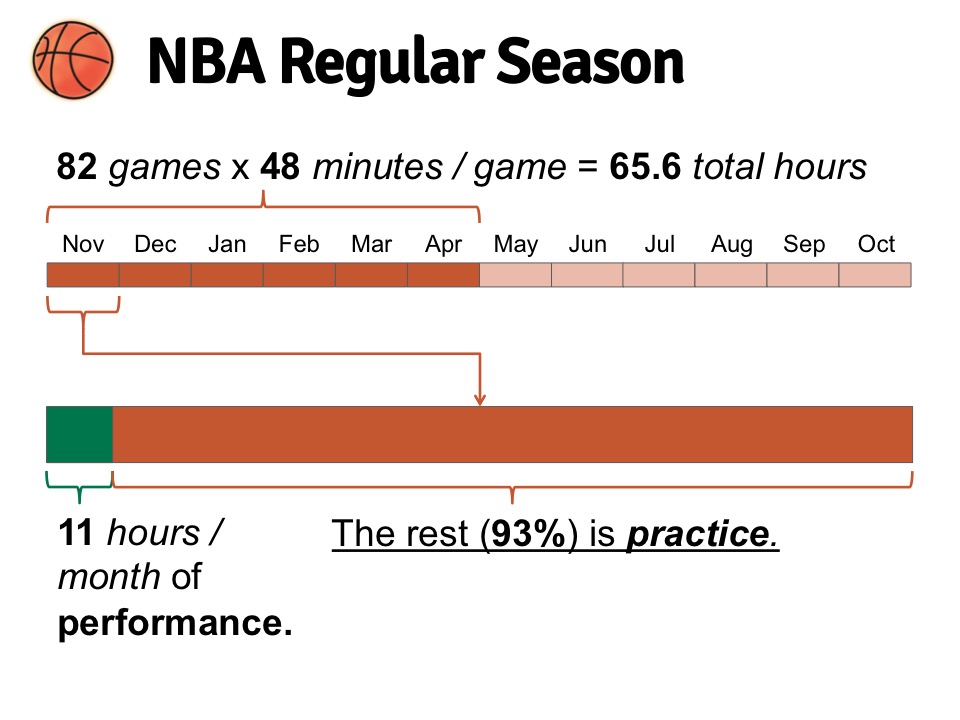

Professional basketball players play six months out of the year — November through April, not including the playoffs. They play 82 48-minute games over the course of their season — about 66 hours total, or 11 hours a month.

11 hours a month! Great job, right? Of course, they’re working a lot more than 11 hours a month. The rest of the regular season — about 93 percent of their actual working time — they’re practicing, training, working on fundamentals, both individually and as a team.

We’re talking well over a 9:1 ratio of practice to performance. Performance, of course, is a form of practice, but the main distinction I’m drawing here is that, when you’re performing, the results count. You can afford to fail a lot when you practice — that’s all part of the process.

Think about your job for a moment. How much of your job relies on collaborating effectively with others? What percentage of your time do you spend practicing versus performing?

I’m not arguing that 9:1 is the right ratio in every context. But I’m going to guess that, for most of you, your ratio is pretty much the opposite of this, and I think that a 1:9 ratio is definitely wrong. Folks who care about getting better rarely consciously consider how they can practice more.

Our predominant culture believes that collaboration is some special knowledge that, once acquired, will magically make groups better. All of our learning mechanisms are oriented this way. We scour articles looking for magical tricks, we invest in magical apps, or we hire consultants whom we hope will share some magical secret.

At the end of the day, none of that works very well. If we want to get better at collaboration, we need to find ways to incorporate a lot more practice, to get our practice-to-performance ratios up.

How do we do this?

Supporting Practice

One way is to provide more structures for encouraging practice. To explain what I mean, consider fitness.

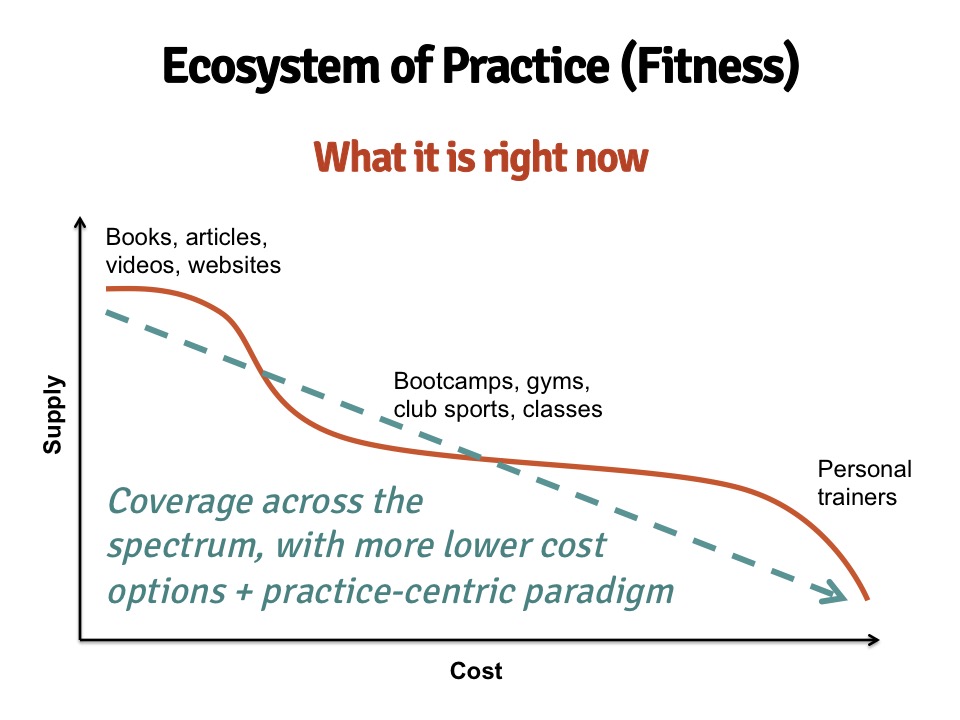

Fitness already has a culture centered around practice. We don’t technically need any structures to help us do that, but structures help. To understand how, let’s map out the ecosystem of structures that support practice in physical fitness along two axes: supply (how much of it is available) and cost.

We’ve got lots of books and free articles on the Internet that give us advice. Those go in the upper left of our chart.

You could work out with a friend or enroll in a gym or take a class or a bootcamp. Some of these things are free, and some cost money, but they’re all still relatively cheap, and there are quite a few options.

You could also hire a personal trainer. These are the most expensive options, and they’re the least used of the options, so we’ll put them on the lower right.

I’m going to claim that this is an ecosystem that more or less works. If we want to get fit, we can find all sorts of structures across a broad price spectrum that will support us in doing so.

What does the collaboration ecosystem look like?

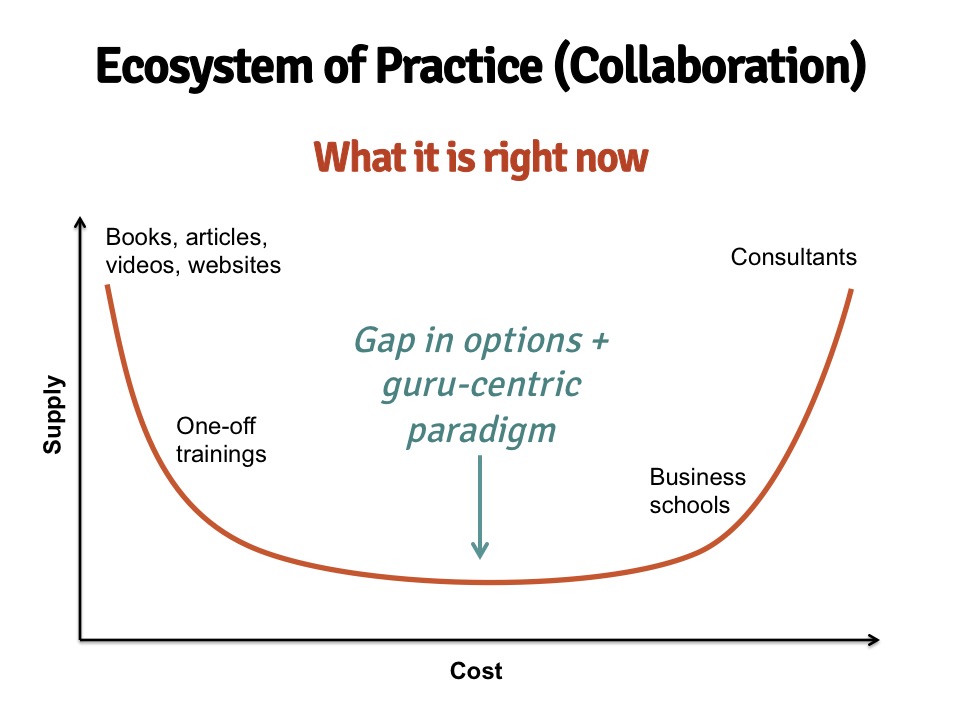

As with fitness, you can easily find thousands of pretty decent articles that explain how to get better at collaboration.

There are plenty of one-off trainings, some of which might even be pretty good.

You could go to business school. This is more on the high-end in terms of cost.

And there are a plethora of folks like me — the equivalent of a personal trainer — you could hire.

This ecosystem favors the high-end. We have very few structures in the middle, which means that there are a lot of people who get left behind.

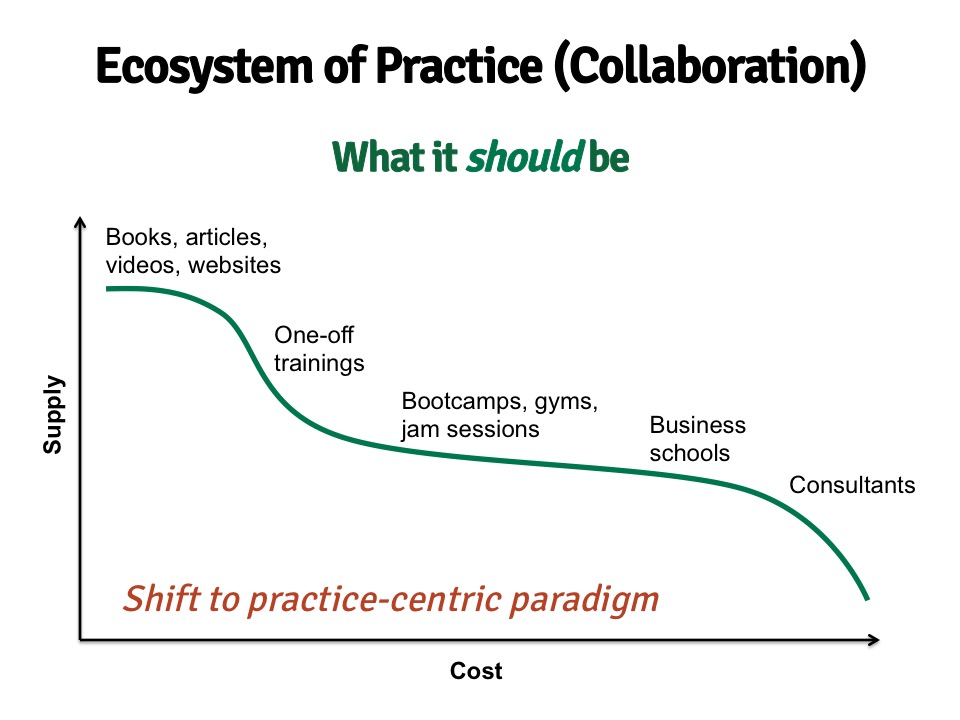

I would argue that, if we want to support more collaboration practice, we need the collaboration ecosystem to look more like the fitness ecosystem.

We don’t need as many options in the high-end, and we need something to fill in the middle. If we could figure out how to shift the collaboration ecosystem so that it looks more like this, then I think more people would be practicing collaboration. If more people practiced collaboration, a lot more groups would be good at it, and we’d start getting closer to this vision of a world where everybody’s baseline experience with collaboration is a great one.

Muscles

How do we shift the collaboration ecosystem so that we’re doing a better job of encouraging and supporting effective practice?

First, we have to get clear about what we’re talking about when we’re talking about “collaboration.” We need to get more concrete about what we mean by “collaboration muscles.”

Collaboration is an aggregation of several skills, some of which are context-dependent. For example, good communication — listening in particular — is clearly important. Your ability to recognize and navigate power dynamics in groups is also important.

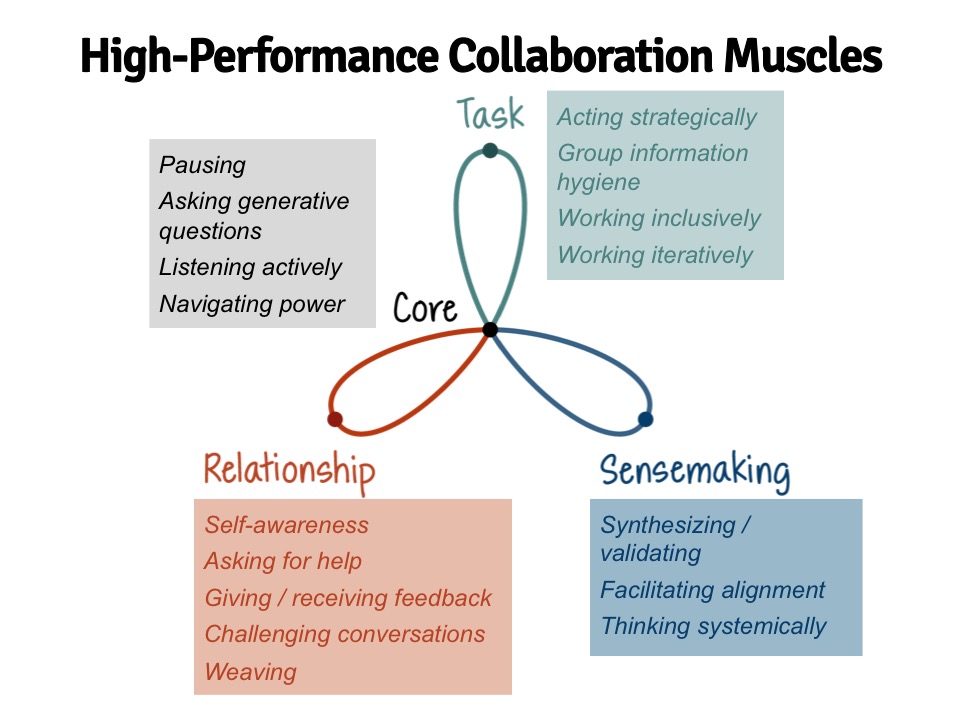

Over the past four years, I’ve identified and refined a set of muscles in four different muscle groups.

Once we’ve identified specific muscles, the exercises (or workouts) start to become clearer. I’ve aggregated a bunch that I use on my website, which I’ve made public domain so that you can do whatever you want with them. I’m not going to say too much more about these now, as we’ll do a listening workout together after I’m done talking, and I’ll be leading power workouts in both the morning and afternoon breakouts.

What’s important to remember about these exercises in the context of practice is that doing them once or a few times or even ten times isn’t enough to be useful. You have to repeat them over and over and over again to develop your muscles, and you have to be intentional about how you practice.

Finally, once we know what the workouts are, we can start developing programs to support them — the equivalent of gyms or bootcamps, the equivalent of exercise “equipment” or apps, muscle assessments, etc. And voila, the ecosystem will start to shift the way we want it to shift.

Shifting Culture

At the end of the day, what I really hope to achieve is a shift in culture. I simply want people to associate improving at collaboration with lots and lots of practice. I hope that all of you walk away from this talk thinking about how you can integrate practice more in your own work and lives, and I hope you’ll try to convince others to do this as well.

If enough of us start doing this, culture shift will happen. Still, I don’t want to make light of how difficult this shift I’m describing will be, both societally and also individually.

Over the past four years, I’ve completely changed how I work with groups. Instead of being a ringer on a basketball team, I’m now their workout instructor. It’s been successful enough that I continue to do this work this way, refining the process along the way. My biggest takeaway, however, has not been how valuable practice is, but how emotionally challenging the journey can be.

To close, I want to share a personal story about what it takes to learn something hard through lots and lots of practice.

One of the things that I am really bad at is learning languages. I don’t speak Korean, which has always been a sore spot for me, as it’s prevented me communicating with many of my relatives and even my own parents, to some extent.

About five years ago, my mom invited me to go to Korea with her. In preparation for this trip with my mom, I decided to enroll in my very first Korean class. I knew that it would take a lot of practice to learn, and I used every trick in the book to try to support me in this. I had lots of people supporting me, and I was super motivated. But I wasn’t having much success, and it was killing me.

At some point, it hit me. Babies are really good at learning languages, and my sister recently had a baby! My nephew, Benjamin, is six now, but he was about one when I was about to go on this trip, so we were both learning a new language at the same time. I decided to watch him closely to see what tips I could pick up from him.

Here’s what I learned. Benjamin, my one-year old nephew, really sucked at speaking English. He was really, really bad. But what was different was that he didn’t expect to be good. When he did speak, everybody — including me — would go nuts! It didn’t matter if what he said made any sense or if he pronounced the words correctly. We would all laugh and coo and celebrate, and he would clearly respond to that. Learning a language, for my one-year old nephew, was a joyful experience, not a painful one.

This was a revelation to me. Benjamin took a good three or four years before he spoke English more or less fluently and correctly, and it was a joyful experience all the way. Here I was, beating myself up after a few weeks of Korean classes, where I wasn’t even fully immersed, thinking for some reason that I needed to be speaking Korean better than I was. What if I assumed that I was going to suck for a long time, and instead of beating myself up for it, celebrated the same way we celebrated Benjamin?

Getting good at collaboration is really hard. It takes practice to get good at it. If we’re really going to get good at it, we all have to learn from Benjamin’s example. We have to understand that we’re going to trip and fall and suck for probably a long time, but we can still celebrate the little victories along the way. And if we give ourselves enough time, we will eventually get so good at it that we won’t even think about it.

Imagine that. What would our world look like if we all became that fluent at collaboration?

Thank you very much!

Thanks, Eugene. Illuminating as ever! I think there is much more to be said about ‘how’ to practice, along the lines of the mastery work: one must push oneself and practice in uncomfortable and difficult ways, not just the easy ones. It would be good to think about the many variations of practice exercises.

I agree, Jodi! Recognizing the importance of practice is just the first step. Figuring out how to practice effectively is critical. I sometimes think of myself as one of those Medieval doctors drilling holes in people’s skulls to relieve the pressure. My understanding of what works is very rudimentary right now.

Great piece