Last year, I got an email out of the blue from Joanna Levitt Cea, Director of Buen Vivir Fund at Thousand Currents and a visiting scholar at the Stanford Global Projects Center. She and her colleague, Jess Rimington, Managing Director of /The Rules, had spent their Stanford fellowship trying to understand why the social sector didn’t seem to be as good as the for-profit sector at innovation. After some extensive research, they had pulled together some preliminary hypotheses, and they wanted to test these with other practitioners.

Neither Joanna nor Jess had heard of me before. A few people had recommended that they talk to me, and they thought enough of my online bio to invite me to a three-day workshop in New Orleans. When I spoke with them, they were incredibly warm and kind. They were curious about my work, and they were humble about theirs. I read an early draft of their research, which I found thoughtful and provocative, and I could see how much hard work they had poured into it.

I was particularly intrigued by their workshop attendees, mainly because I didn’t know any of them, which surprised me. I’ve been in this field for 15 years, and I’m obsessed with finding other great practitioners, yet I had never heard of any of these other attendees or their work. Googling didn’t turn up much either, but I found enough to interest me. For example, two of the practitioners were the hosts of our workshop: Steven Bingler and Bobbie Hill of Concordia, a community-centered planning and design firm. Among their many, many great projects was the Unified New Orleans Plan, a five-month planning process they led following Hurricane Katrina, which involved 9,000 residents and resulted in a comprehensive redevelopment plan.

I arrived at Steven’s house not knowing a soul, and he and Bobbie immediately made sure I and all the other attendees felt at home. Everyone was warm and friendly, and we bonded over crawfish, crab, and conversation before heading to Poplarville, Mississippi for our retreat. I rode in Bobbie’s car, where we talked about our lives and shared our respective journeys. I later got to learn more about Steven’s vision and philosophy as well.

I was struck by how different our backgrounds were, yet how similarly we approached the work and how aligned our values were. After getting to know Steven and Bobbie better, as well as the other participants, I was even more surprised that we had never heard of each other before. I thought Steven might have heard of Matt Taylor, one of my mentors, because they were both architects, but he hadn’t.

One of my favorite sayings when describing this work is, “Chefs, not recipes.” This simple phrase encapsulates everything I believe about the craft of collaboration, but it also says a lot about high-performance ecosystems. As it turns out, the chef scene is very tight. Everyone who cooks seriously — from top chefs to rising cooks — seems to know each other.

Part of this is due to the popularization of food culture and all the trappings that come with it — celebrity chefs, reality television, food blogs, and so forth. However, the roots of this tight-knit, informal network are far older and deeper. Cooks have long had a culture of staging (i.e. apprenticeship) as a way of learning the craft. Not only do cooks taste each other’s food, they often work side by side with other cooks to see how that food is made. Because of this, cooks not only know each other, they are intimately familiar with each other’s work.

That is not my experience with my field. Why is this? What would be possible if this were not the case?

Joanna and Jess recently wrote about their work in a Stanford Social Innovation Review article entitled, “Creating Breakout Innovation.” I think the whole piece is excellent, and I plan on playing with their assessment tool. I was particularly struck by this conclusion:

We found that actors delivering such breakout results cocreated in ways that represent a significant rupture from mainstream practice within their field. In fact, we were surprised to find that many of the big names in cocreation — including those speaking the loudest about seemingly cutting-edge practices like “collective impact,” “crowdsourcing,” and “design thinking” — were not actually significantly departing from the status quo, particularly when it came to generating a shift in power, voice, and ownership. Instead, breakout actors tend to be on the fringes of their fields.

I’m not surprised by this, but I’m troubled by it. The best practitioners I know in this space are fundamentally motivated to lift others up and couldn’t care less about talking about themselves. They are classic yellow threads — leaders who brighten everyone around them while remaining mostly invisible themselves.

There is something admirable about this, but it’s also extremely problematic. If people don’t share these stories themselves, who will? If we’re not learning about these stories or about the people responsible for them, how will the rest of us know where to go to learn, to stage?

Not surprisingly, Joanna and Jess themselves fall prey to this mindset in their article. One of the breakout projects they mention in their article is the Health eHeart initiative, a brilliant example of participatory design led by my friends and colleagues, Rebecca Petzel and Brooking Gatewood. Joanna and Jess mentioned Emergence Collective, the brand under which Rebecca and Brooking are working, but they never mentioned either of them by name.

As it turned out, this was intentional. They didn’t mention any individual practitioners unless they were quoting them. Why not? I recently asked them, and they had a predictably thoughtful answer: They didn’t want to overly shine attention on individuals when so many people were involved. However, in multiple cases, they did mention an individual’s name, and the individual asked them to replace it with the group name!

Clearly, most of the practitioners either didn’t care that they weren’t mentioned or didn’t want to be mentioned. Well, I care, and I want my peers, whom I respect so much, to start caring too. By not celebrating this less ego-centric form of leadership, we enable models that don’t work and the practitioners responsible for them to perpetuate. Invisibility doesn’t serve the work.

In fairness to Joanna and Jess, I had multiple opportunities to give them this feedback before the article was published, and I didn’t. It took a while to coalesce in my brain, which perhaps speaks to how foreign this kind of thinking is to many of us. I’m definitely not the best model of this highlighting behavior, at least not on the surface. I give my work away, and I do not require credit. I have seen other firms attempt to take credit for my work and have just shrugged my shoulders. I’m usually mentioned in projects I’m involved with, but not prominently (which is intentional). As a facilitator, my goal is to hold the space without being at the center of it. To this day, there are a number of people who have participated in meetings I’ve been involved with who think I’m a professional photographer, because that’s what they saw me doing.

None of this bothers me, because it’s not why I do the work, and I get all the credit I need to live a happy life. Frankly, I hate it when I hear people, who haven’t actually seen me work, speak glowingly about me. I’m flattered that people think highly of me, but I want them to withhold judgement until they actually experience my work side by side, as cooks do.

Maybe all of this is a disservice to my point about invisibility. I’ve been reflecting a lot about this recently, and I’ll probably try some different things. But there are a number of things I already do that serve my larger goals:

- I try to amplify any great work I hear about, regardless of who did it

- I don’t take on work I can’t talk about

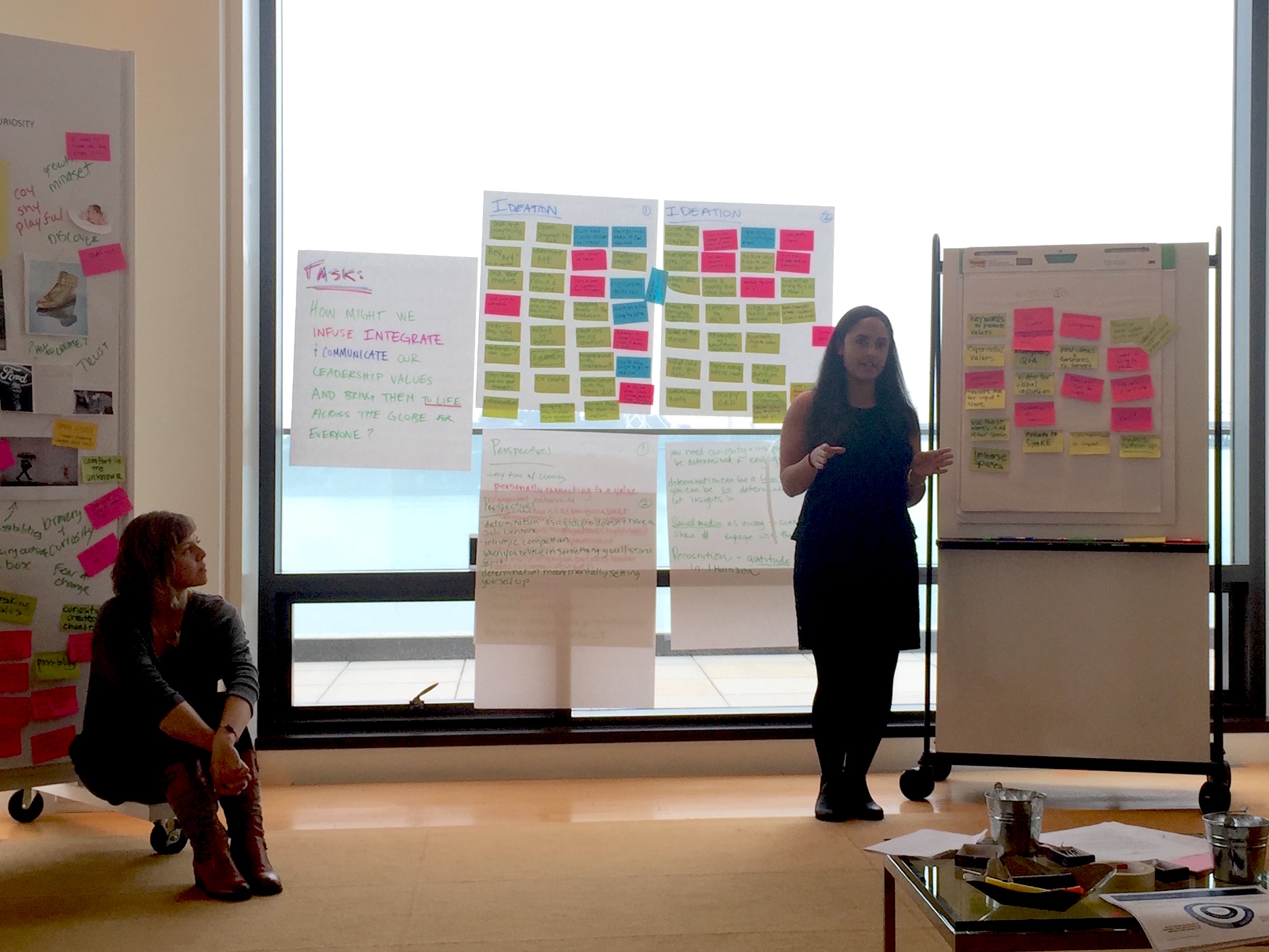

- I try to tell the story of my work in real-time. For the past seven years, I have intentionally made storytelling a (budgeted) priority on many of my projects.

- I encourage people to shadow my work

- While I don’t go out of my way to talk about myself, I don’t shy away from it either. I happily take credit for what I do well and responsibility for what I do poorly. This blog is evidence of that.

I’d like to see more of my peers practice all of these things, especially this last point, which I think will be the hardest thing for most of them to do. That includes Joanna and Jess. They have already transcended what most of us do by investing so much of their own time to find and tell these stories. They not only lifted up other people, they did so with rigor while also living into their own principles.

What makes them particularly unique is that they are not academics. They themselves are practitioners who have stories worth sharing. I hope that they — and all of my peers — start to value their own leadership as much as they’ve valued others. I hope that we, as a community, can find ways to lift and celebrate our own and each other’s stories.

Thanks to Anya Kandel and H. Jessica Kim for reviewing early drafts of this post.

Update (June 22, 2017): Joanna and Jess informed me that, in several cases, they did mention individual names, but those individuals asked that their names be replaced by the group’s name. I’ve updated the post to reflect this.

Soon after joining Gap Inc., I started to explore how to create alternate spaces for communication that could scale and that skirted hierarchical limitations.

Soon after joining Gap Inc., I started to explore how to create alternate spaces for communication that could scale and that skirted hierarchical limitations. Eugene’s work has complemented a deficiency I found in many innovation and co-creation initiatives, including my own:

Eugene’s work has complemented a deficiency I found in many innovation and co-creation initiatives, including my own: