In 2009, I was asked by the Wikimedia Foundation to design and lead a movement-wide strategic planning process. The goal was to create a high-quality, five-year strategic plan the same way that Wikipedia was created — by creating a space where anyone in the world who cared could come and literally co-author the plan.

We had two fundamental challenges. First, it wasn’t enough to simply have a plan. It had to be a good plan that some significant percentage of the movement both understood and felt ownership over.

Second, we were asking people in the community to develop a strategy, but most people had no idea what strategy was. (This, frankly, is true of people in general, even in business.) It was different from Wikipedia in that most people already have a mental model of what an encyclopedia is. We had to be more concrete about what it was that we were asking people to do.

I explained that strategic planning, when done well, consists of collectively exploring four basic questions:

- Where are we now?

- Where do we want to go? Why?

- How do we get there?

I further explained that we were going to create a website with these questions, we were going to get as many people as possible to explore these questions on that website, and by the end of the year, we would have our movement-wide, five-year strategic plan.

And that’s essentially what we did.

Get the right people to explore core questions together. Where are we now? Where do we want to go, and why? How do we get there? Provide the space and the support to help these people have the most effective conversation possible. Trust that something good will emerge and that those who created it will feel ownership over it.

This is how I’ve always done strategy, regardless of the size or shape of the group. It looks different every time, but the basic principles are always the same. People were intrigued by what we accomplished with Wikimedia, because it was global and primarily online, because we had gaudy results, and because Wikipedia is a sexy project. However, I was simply using the same basic approach that I use when working with small teams and even my own life.

The craft of developing strategy is figuring out how best to explore these core questions. It’s not hard to come up with answers. The challenge is coming up with good answers. To do that, you need to give the right people the opportunity and the space to struggle over these questions. That process doesn’t just result in better answers. It results in greater ownership over those answers.

Breakfast and Culture

What’s your strategy for eating breakfast in the morning?

Are you a grab-and-run person, either from your own kitchen or from a coffee shop near your office? Eating breakfast at home is cheaper than eating out, but eating out might be faster. Are you optimizing for time or money? Why?

Maybe you have kids, and you value the ritual of kicking off the day eating together? Maybe you’re a night owl, and you’d rather get an extra 30-minutes of sleep than worry about eating at all in the morning.

Where do you want to go? Why? How do you get there? These are key strategic questions, but you can’t answer them without also considering culture — your patterns of behavior, your values, your mindsets, your identity. Choosing to cook your own meals is as much a cultural decision as it is a strategic one.

In my past life as a collaboration consultant, groups would hire me to help with either strategy or culture, but never both. I realized fairly quickly that trying to separate those two processes was largely artificial, that you couldn’t explore one without inevitably colliding with the other.

Peter Drucker famously said, “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” He did not intend to say that one was more important than the other, but that both were necessarily intertwined. Or, as my friend, Jeff Hwang, has more accurately put it, “Saying culture eats strategy for breakfast is like saying your left foot eats your right foot for breakfast. You need both.”

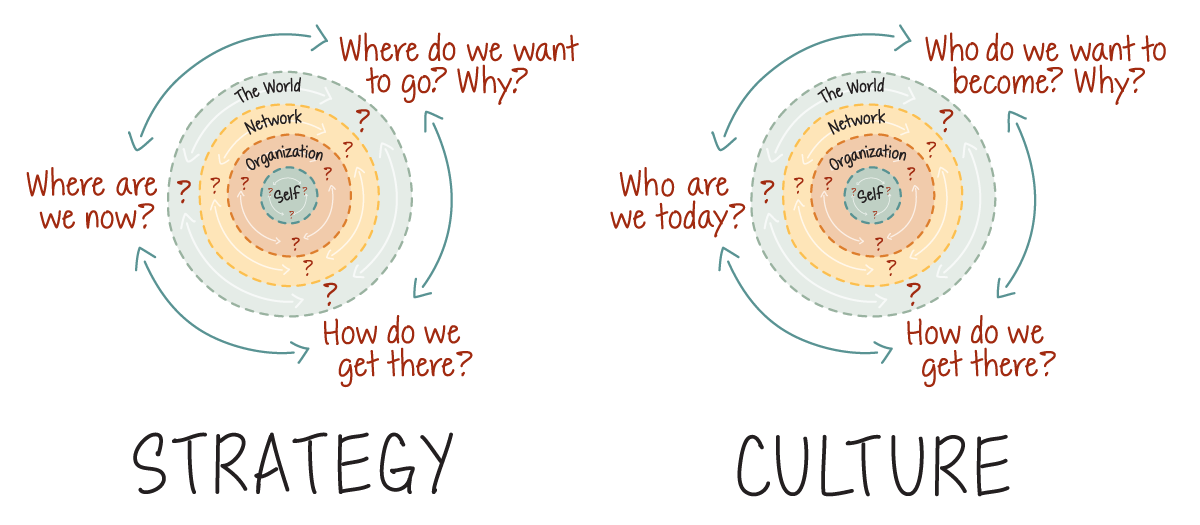

As with strategy, culture work is a process of collective inquiry, except instead of focusing on action (where do you want to go?), the questions are centered around identity:

- Who are we now?

- Who do we want to be, and why?

- How do we get there?

The key to effective culture work is to explore these questions yourself, to struggle over them together as a group, and to constantly revisit them as you try things and learn.

DIY Strategy and Culture

Toward the end of 2013, Dharmishta Rood, who was then managing Code for America’s startups program, asked me if I would mentor one of its incubator companies, which was having some challenges around communication and decision-making. I had been toying with some ideas for a do-it-yourself toolkit that would help groups develop better collaborative habits on their own, and I suggested that we start there.

We immediately ran into problems. The toolkit assumed that the group was already aligned around a core strategy, but with this group, that wasn’t the case. They had been going, going, going without stopping to step back and ask themselves what they were trying to accomplish, how they wanted to accomplish those things, and why. (This is very typical with startups.)

This group needed space to do some core work around strategy and culture. I threw out my old toolkit and created a new one designed to help groups have strategy and culture conversations continuously and productively on their own. The revised toolkit was based on the key questions underlying strategy and culture depicted as two cyclical loops:

While most strategy or culture processes are progressively staged, in practice, inquiry is never linear, nor should it be. Spending time on one question surfaces new insights into the other questions, and vice-versa. Where you start and the order in which you go are not important. What matters is that you get to all of the questions eventually and that you revisit them constantly — hence the two cycles. My colleague, Kate Wing, recently noted the resemblance of the diagram to bicycle wheels, which is why we now call it the Strategy-Culture Bicycle.

Dharmishta and I saw the Bicycle pay immediate dividends with this group. People were able to wade through the complexity and overwhelm, notice and celebrate what they had already accomplished, and identify high-priority questions that needed further discussion. Furthermore, the process was simple enough that it did not require a third-party’s assistance. They were able to do it fine on their own, and they would get better at it as they practiced.

Pleased and a bit surprised by its effectiveness, I asked my long-time colleague, Amy Wu of Duende, to partner with me on these toolkits. We prototyped another version of the toolkit with four of last year’s Code for America accelerator companies, and once again, saw great success.

We’ve gone through eight iterations together, we’ve tested the kit with over a dozen groups and individuals (for personal and professional life planning), and we’ve added some complementary components. A number of practitioners have used the toolkit on their own to help other groups, including me, Dharmishta, Amy, Kate, and Rebecca Petzel.

I’m thrilled by the potential of toolkits like these to help build the capacity of practitioners to act more strategically and to design their aspired culture. As with all of my work, these toolkits are available here and are public domain, meaning that they are freely available and that you can do anything you want with them. You can also purchase pre-printed packages.

Please use them, share them, and share your experiences! Your feedback will help us continuously improve them.