Today marks the 45th anniversary of the Mother of All Demos, where technologies such as the mouse and hypertext were unveiled for the first time. I wanted to mark this occasion by writing about collective intelligence, which was the driving motivation of the mouse’s inventor (and my mentor), Doug Engelbart, who passed away this past July.

Doug was an avid churchgoer, but he didn’t go because he believed in God. He went because he loved the music.

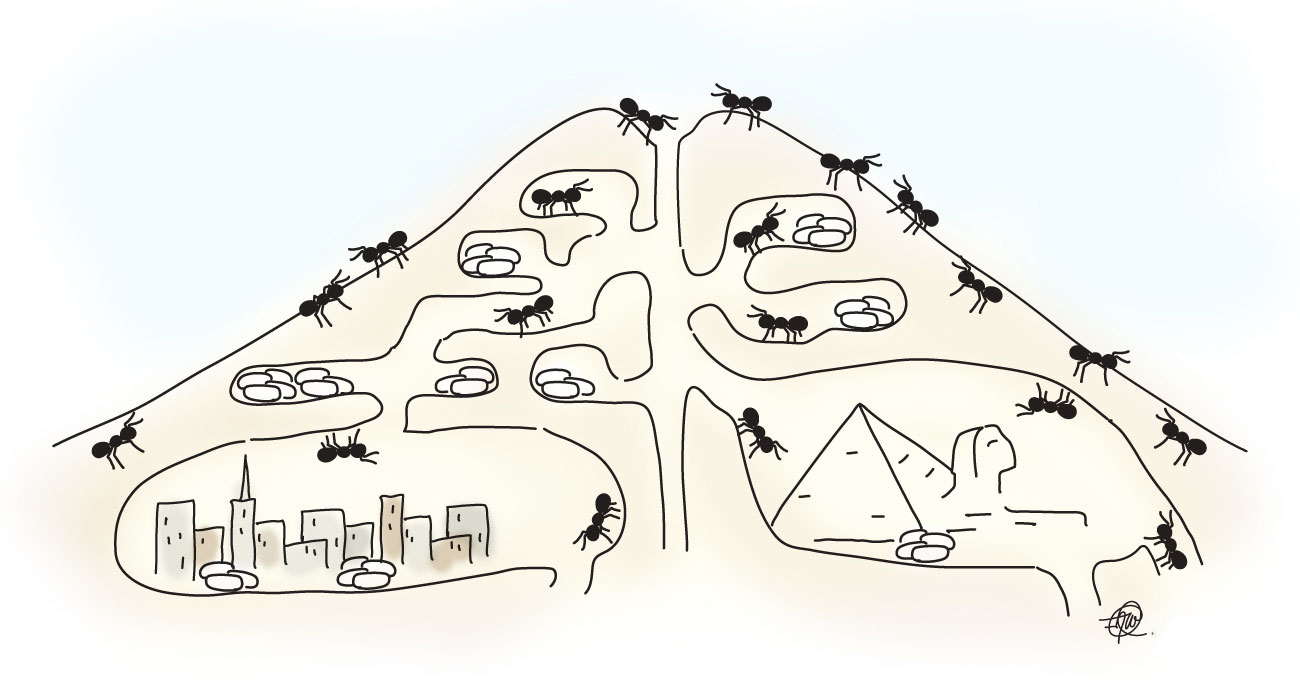

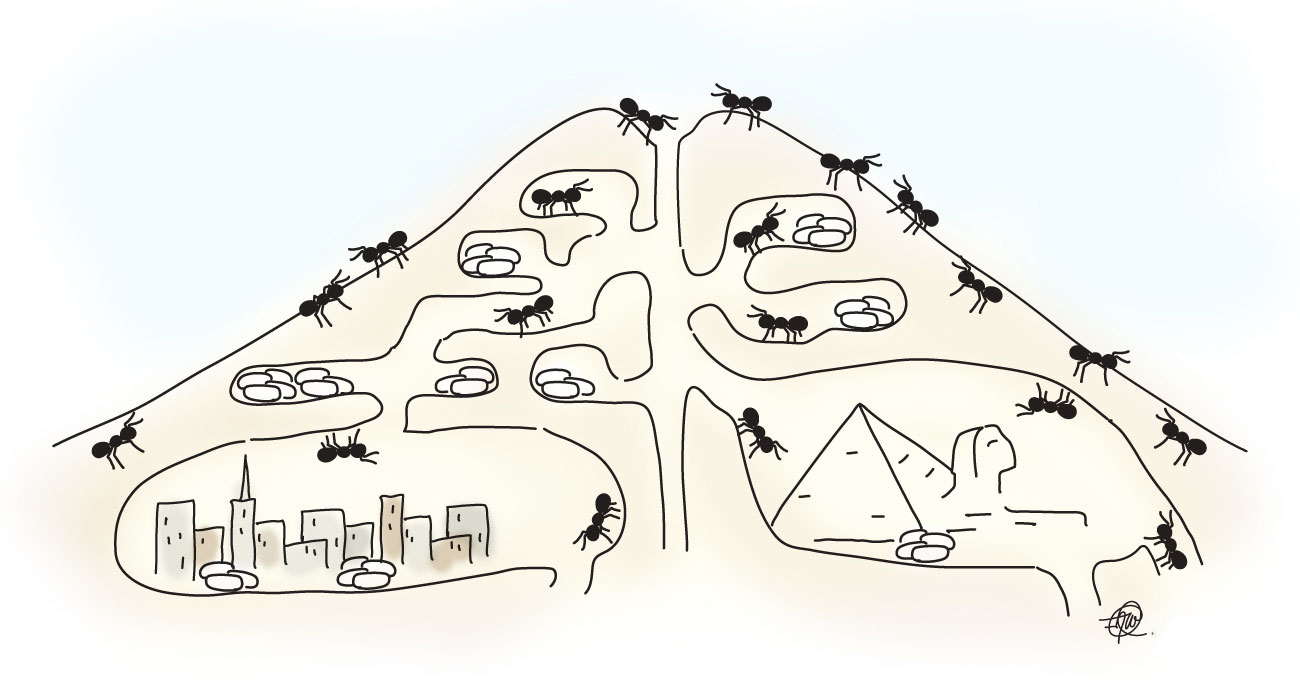

He had no problem discussing his beliefs with anyone. He once told me a story about a conversation he had struck up with a man at church, who kept mentioning “God’s will.” Doug asked him, “Would you say — when it comes to intelligence — that God is to man as man is to ants?”

“At least,” the man responded.

“Do you think that ants are capable of understanding man’s will?”

“No.”

“Then what makes you think that you’re capable of understanding God’s will?”

While Doug is best known for what he invented — the mouse, hypertext, outlining, windowing interfaces, and so on — the underlying motivation for his work was to figure out how to augment collective intelligence. I’m pleased that this idea has become a central theme in today’s conversations about collaboration, community, collective impact, and tackling wicked problems.

However, I’m also troubled that many seem not to grasp the point that Doug made in his theological discussion. If a group is behaving collectively smarter than any individual, then it — by definition — is behaving in a way that is beyond any individual’s capability. If that’s the case, then traditional notions of command-and-control do not apply. The paradigm of really smart people thinking really hard, coming up with the “right” solution, then exerting control over other individuals in order to implement that solution is faulty.

Maximizing collective intelligence means giving up individual control. It also often means giving up on trying to understand why things work.

Ants are a great example of this. Anthills are a result of collective behavior, not the machination of some hyperintelligent ant.

In the early 1980s, a political scientist named Robert Axelrod organized a tournament, where he invited people to submit computer programs to play the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma, a twist on the classic game theory experiment, where the game is repeated over and over again by the same two prisoners.

In the original game, the prisoners will never see each other again, and so there is no cost to screwing over the other person. This changes in the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma, which means there’s now an incentive to cooperate. Axelrod was using the game as a way to try to understand the nature of cooperation more deeply.

As it turned out, one algorithm completely destroyed the competition at Axelrod’s tournament: Tit for Tat. Tit for Tat followed three basic rules:

- Trust by default

- The Golden Rule of reciprocity: Do unto others what they do unto you.

- Forgive easily

Axelrod was intrigued by the simplicity of Tit for Tat and by how easily it had trounced its competition. He decided to organize a followup tournament, figuring that someone would figure out a way to improve on Tit for Tat. Even though everyone was gunning for the previous tournament’s winner, Tit for Tat again won handily. It was a clear example of how a set of simple rules could result in collectively intelligent behavior, highly resistant to the best individual efforts to understand and outsmart it.

There are lots of other great examples of this. Prediction markets consistently outperform punditry when it comes to forecasting everything from elections to finance. Nate Silver’s perfect forecasting of the 2012 presidential elections (not a prediction market, but similar in spirit) was the most recent example of this. Similarly, there have been several attempts to build a service that outperforms Wikipedia by “correcting” its flaws. All have invoked the approaches people took to try to beat Tit for Tat. All have failed.

The desires to understand and to control are fundamentally human. It’s not easy to rein those instincts in. Unfortunately, if we’re to figure out ways to maximize our collective intelligence, we must find that balance between doing what we do best and letting go. It’s very hard, but it’s necessary.

Remembering Doug today, I’m struck — as I often am — by how the solution to this dilemma may be found in his stories. While he was agnostic, he was still spiritual. Spirituality and faith are about believing in things we can’t know. Spirituality is a big part of what it means to be human. Maybe we need to embrace spirituality a little bit more in how we do our work.

Miss you, Doug.

Artwork by Amy Wu.