Four years ago, I started organizing a small end-of-year gathering with other Bay Area collaboration practitioners to celebrate and make meaning of the year together. We would spend the first few hours of our session mapping how our individual years went using an exercise called Journey Mapping, then we would share our respective stories with each other and toast the end of the year with libations and snacks. It was a lovely ritual, and it became an annual tradition.

This past year, we couldn’t do a face-to-face gathering due to the pandemic, so we decided to do it remotely instead. Going remote had three wonderful benefits. We were able to divide it into two sessions, which netted us more time. We were able to invite more people, including folks who lived outside of the Bay Area. And, it was a good kick-in-the-pants for me to write up the exercise so that others could organize their own gatherings. (Several folks did, which made me incredibly happy.)

Journey Mapping is a quick way of visually telling the story of a project’s highs and lows over a bounded timeline. (Product managers may be familiar with customer journey mapping, which is similar in spirit, but different in practice.) You can do the exercise on your own, but it’s nicer in a group setting, even when everyone is doing it for themselves (as we do in our end-of-year ritual). It’s like working out with a buddy — you’re more likely to do it if others are doing it with you, and it’s a wonderful way to support each other and build community. When you do it as a group on a shared project, it serves as a fantastic tool for making meaning together and for discussing and developing shared narratives. I often use it as a ritual for teams to celebrate, mourn, learn, and transition.

How you do the exercise is not as important as simply making time to reflect regularly. The more you do it, the more you’ll understand how best to adjust it for your specific situation. That said, Journey Mapping has three attributes that I think are particularly powerful.

First, it contextualizes your work in your overall life. The toolkit specifically asks you to map highs and lows both professionally (or with a specific project) and personally. In a team setting, the tendency is to skip the personal brainstorming, especially when you have limited time. Sometimes, this is warranted. However, you lose a lot when you do this. Several years ago, I did this exercise with a startup’s leadership team, which was struggling mightily with interpersonal dynamics. Earlier that year, they had been running out of money, and they weren’t sure they would be able to raise another round of investments. Not surprisingly, that was a low point professionally for everyone. At the same time, one of the leaders had also been dealing with a family tragedy and the dissolution of a relationship. The rest of the team never knew about this and only found out about this through the Journey Mapping exercise. Learning about their teammate’s personal struggles many months after the fact caused them to re-examine how they viewed their behavior during that time, leading to greater empathy, a little regret, and ultimately forgiveness.

Second, the Journey Mapping exercise asks you to list the highs and lows from memory first, then to review your calendar, journal, and other artifacts and add anything you might have forgotten. This reminds you that what you might be feeling and remembering in the moment is rarely the whole story and that there may be lessons to harvest or things to celebrate that are worth revisiting. It also reminds us of the importance of having and reviewing artifacts.

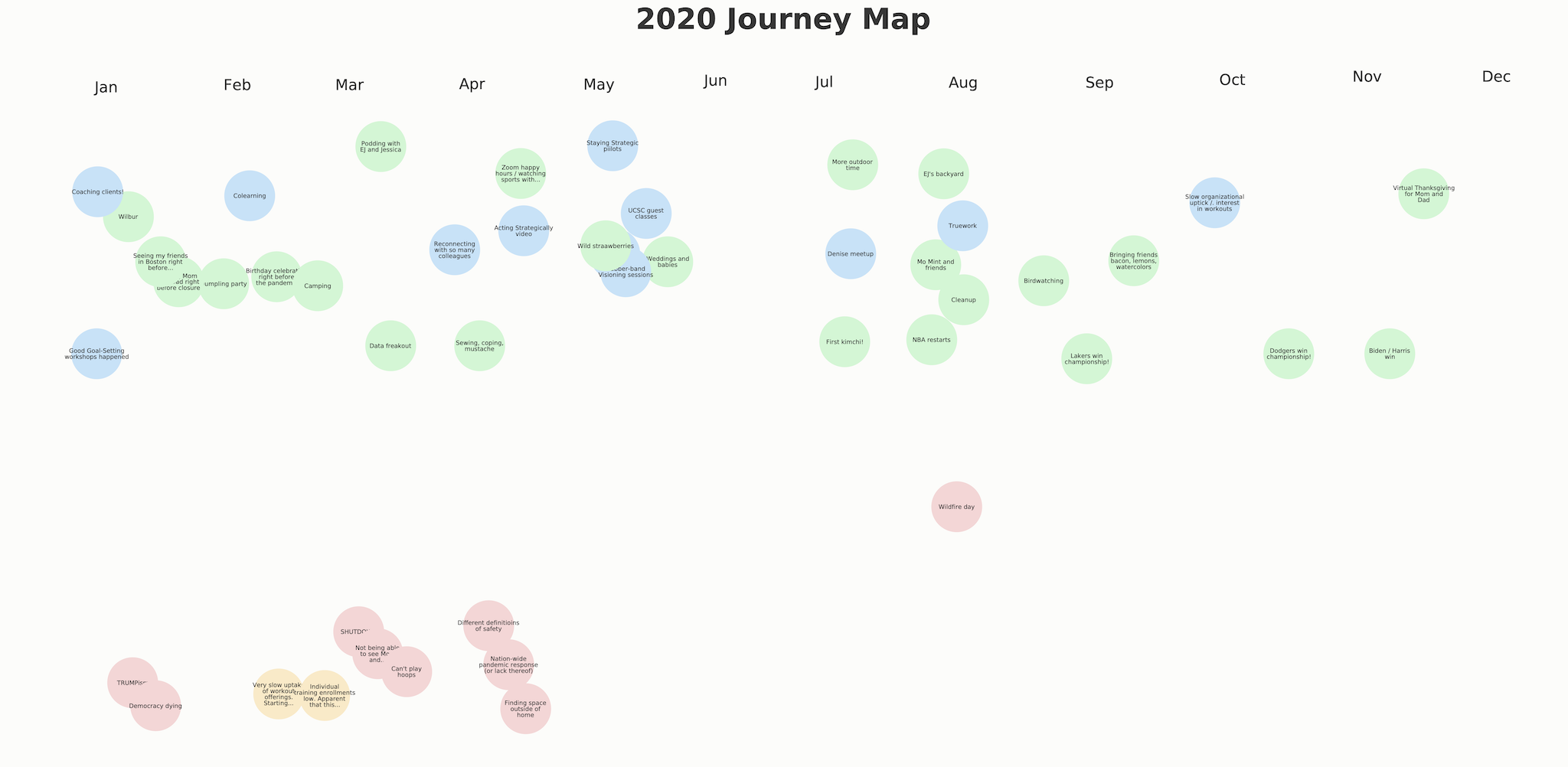

Third, the Journey Mapping exercise encourages you to take your somewhat structured set of sticky notes and create meaningful art out of it. For example, these were the sticky notes that I created for my 2020 (using Sticky Studio):

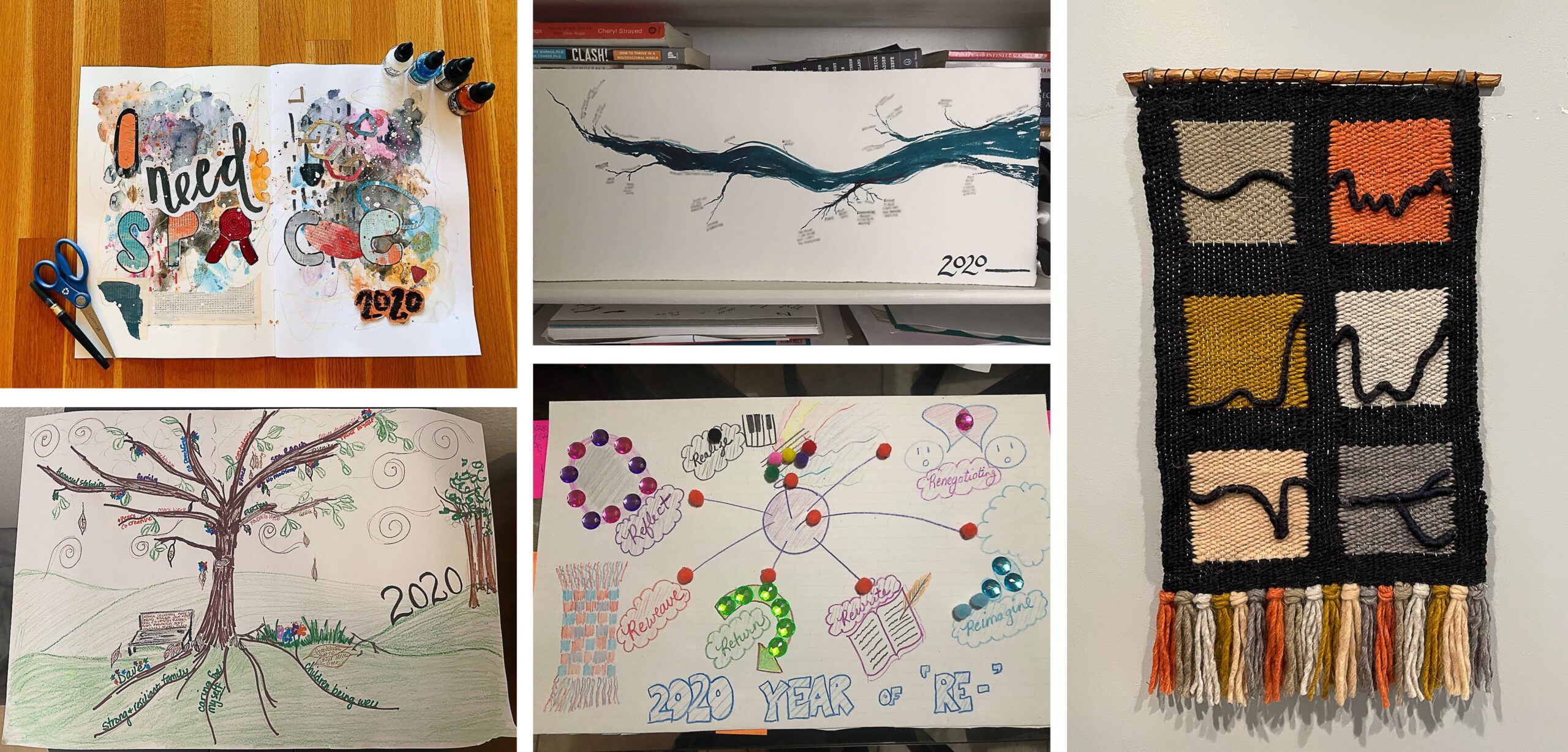

and this was my artistic rendition:

This part of the exercise almost always gets short shrift. We often treat art as optional — nice, but not necessary. Doing this end-of-year ritual with my colleagues the past four years has helped me realize that this is a mistake, not just with Journey Mapping, but with many of my exercises. Practically speaking, when you create something that’s beautiful, you’re more likely to look at it again. More importantly, the act of creation leads to an understanding that’s far deeper and more meaningful than a set of sticky notes can convey.

You can get a taste of what I mean by looking at the art that some of my colleagues created:

Everybody chose to tell their story differently, from emphasizing specific themes (e.g. needing space, “re-“ words) to capturing a larger metaphor (e.g. tree, river). My colleague, Catherine Madden, organized her year into five categories and wove her story into the tapestry on the right — you can read more about her story and process here. Seeing what people created and listening to their stories were incredibly moving. I will remember those stories in a way that I don’t think would have been possible if they had simply told them or shared their sticky notes. Moreover, I don’t know that they would have told the stories the way they did if they had not had the chance to create this art.

My 2020

The personal backdrop for my 2020 was — like everyone’s — all about the pandemic. I was incredibly fortunate to be healthy and safe and not to lose anyone to COVID-19. So many people were not that lucky. The numbers are staggering — 2.2 million deaths worldwide so far, 450,000 in the U.S alone. (For comparison, 400,000 Americans died in World War II.) What made it all the more heartbreaking — especially for someone whose purpose is to help society collaborate more effectively — was how divided and misaligned we were in these trying times.

I was way luckier than most, but pandemic life was still hard. I spent the spring simply trying to cope. Like many people, one mechanism I tried was growing plants. I found a wilted mint sprig in the back of my refrigerator, which I rooted in water for several weeks, then transferred to a pot. I observed and documented the process every day, occasionally sharing what I saw on Instagram. My partner, amused by the loving care I was showing my plant, named it, “Mo.” I was awed by how resilient my mint was, and I was also surprised how gratifying this simple, regular practice of paying attention to Mo Mint felt.

Resilience. Paying attention. These became recurring themes both personally and professionally. I went into 2020 hoping that I could spend 30 percent of my time on coaching and training individual collaboration practitioners. I felt that this would be the best path to maximizing my impact, and it’s also where I felt the most energy and joy. A third of the way into the year, as the lockdowns were starting, it was clear that I wasn’t getting enough traction to hit that number.

I also went into 2020 adamant that I would only take on organizational clients willing to try my muscle-building approach to addressing their challenges. Convincing clients to do this has always been difficult, but my yield in the first half of 2020 was even lower than what it usually was. In an interesting twist, both the pandemic and the racial unrest created demand around collaboration practitioners who could help with remote work and equity work. However, most of the prospects who came my way were more interested in quick fixes than the kind of deep work that real change requires.

Grappling with those two things in concert was hard enough. Doing so during a pandemic was even harder. Paying attention and focusing on resilience made all the difference in the world.

The previous year, I had started to experiment with video as a way to better communicate my frameworks and practices, and I had more ideas and partially written scripts than time to produce them. Several conversations I had been having with colleagues inspired me to revisit one of these videos, Acting Strategically, which I published in April.

The response was universally positive, with many people asking me, “What would it look like for me or my organization to do this?” This led me to dust off some workouts I had developed over the years and start piloting them with colleagues and friends. The pilots performed well, and I loved doing them. I started preparing an “official” offering for late 2020, when something unexpected happened. Focusing on strategy was helping prospective organizational clients understand my workout approach in a way that had failed to click otherwise. Even when it was clear that they needed to focus on areas other than strategy, because they were better primed for this approach, they were more open to using workouts to address other aspects of collaboration.

By late summer, I found myself doing workouts with several organizational clients. It was gratifying and generative, but it was also taking my energy away from my individual practitioner offerings. I was conflicted, but I ultimately decided to go with where the demand was taking me and to hold off on my individual offerings indefinitely.

Looking Forward and Backward and Forward Again

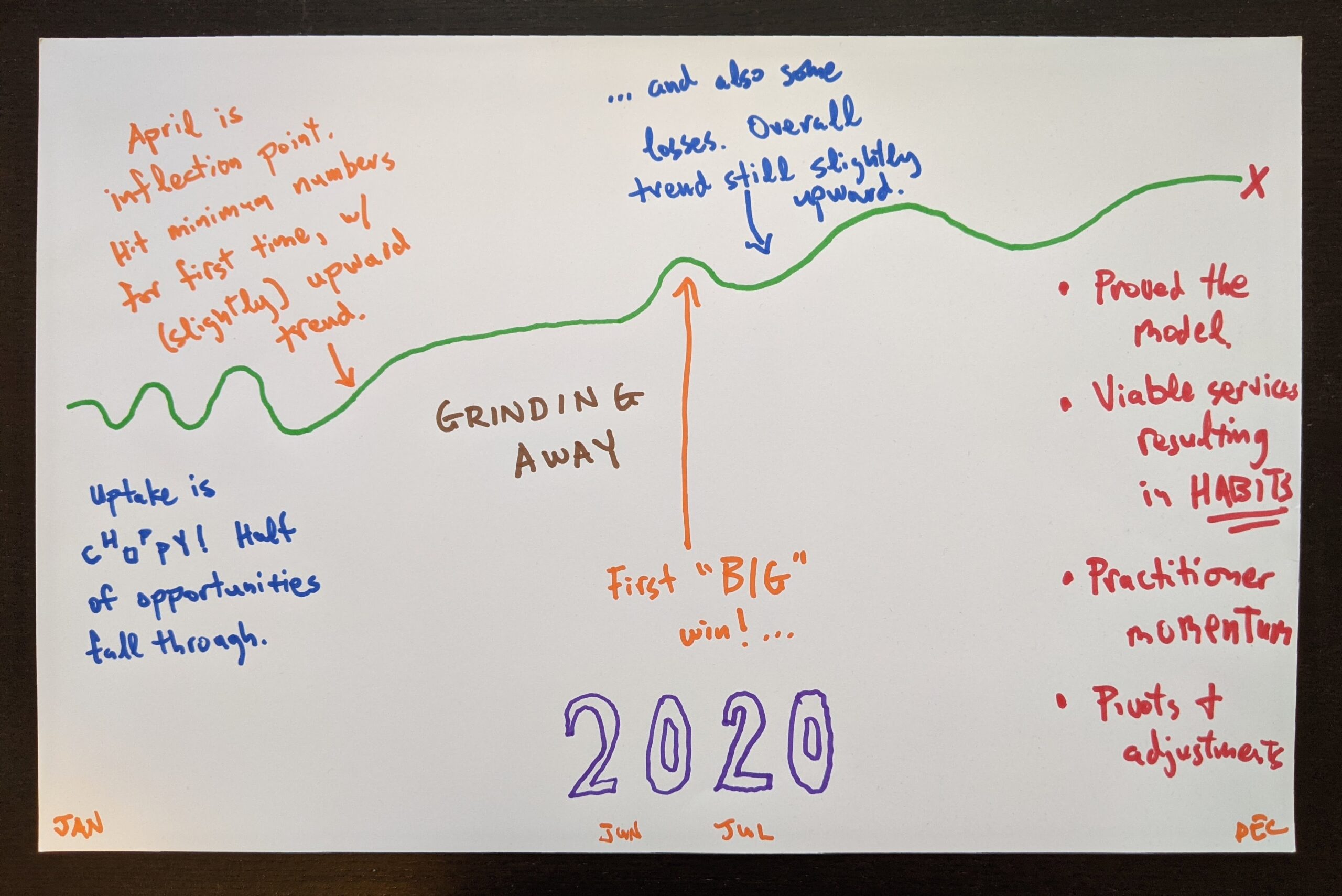

Doing the Journey Mapping this past December had one more interesting twist. A few years earlier, Catherine Madden had suggested doing the exercise as a way of looking forward, not just looking back. At the beginning of 2020, I decided to try her suggestion, drawing what I imagined my professional curve might look like at the end of 2020. Here’s what I drew:

It was fascinating to compare this with how my year actually went. I had imagined a choppy beginning with a gradual upward trend, and I wasn’t completely wrong. However, the choppiness ended up being twice as long with an overall downward trajectory, there was never any “big” win, and while my year did end on an higher note, it wasn’t as high as I had hoped.

Still, as with all scenario work, the goal wasn’t prediction, it was to prepare for possibilities. Because I had imagined that my year would be choppy initially, I was mentally and emotionally prepared when that turned out to be true. I had also adjusted my strategic goals accordingly, so even though they ended up being off, they were not as off as they probably would have been otherwise. Finally, because I had written it all down, I had something to look at and reflect on at the end of the year.

I am determined to do this exercise again for 2021, but it’s already February. I’m about two months behind where I usually am in terms of planning, and I find myself more unmoored than I’ve been since starting this Faster Than 20 experiment seven years ago. I’m trying to be compassionate with myself. Last year was not normal, and while there are some positive signs, we’re not out of the woods yet, and there’s still a lot of uncertainty moving forward. I’m still excited about providing workouts, coaching, and community for collaboration practitioners. I have a set of clients I’m currently supporting, I have some ideas of what I want to offer individual practitioners later this year, and I will undoubtedly continue to experiment. Beyond that, I just don’t know.

What I do know is that rituals, community, and time to reflect matter. I am always grateful for my peers and our end-of-year gathering, but I feel especially so now. I hope many of you find Journey Mapping valuable as well.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS