COVID-19 has forced many of us to reckon with a working world where we can’t be face-to-face. I’ve been heartened to see how collaboration practitioners have been responding overall. I love seeing folks tapping the wisdom of their own groups before looking outward and sharing their knowledge freely and broadly.

I am especially happy to see people reminding others and themselves to pause and revisit their underlying goals rather than make hasty decisions. There is a lot of amazing digital technology out there, and it’s easy to dive head-first into these tools without considering other, technology-free interventions that might have an even greater impact in these difficult times. It’s been interesting, for example, to see so many people emphasize the importance of checkins and working agreements. When this is all over, I hope people realize that these techniques are relevant when we’re face-to-face as well.

After all, online collaboration is just collaboration. The same principles apply. It just takes practice to get them right in different contexts.

One adjustment I’d like to see more people make is to focus less on meetings. (This was a problem in our pre-COVID-19 world as well.) Meetings are indeed important, and understanding how to design and facilitate them effectively, whether face-to-face or online, is a craft that not enough people do well. However, meetings are just a tool, and a limited one at that. I’d like to offer two frameworks that help us think beyond meetings.

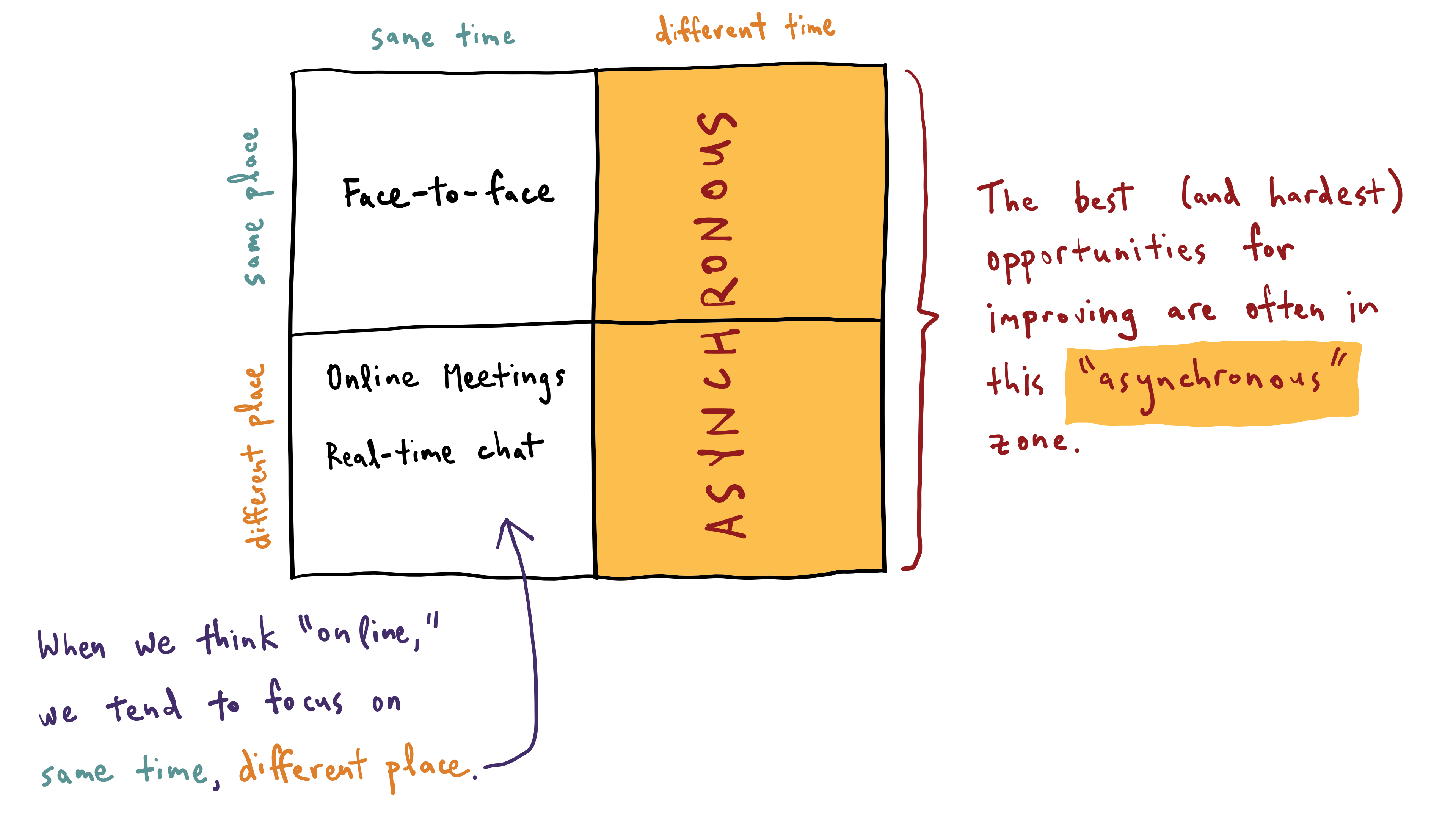

First, try not to think in terms of “online” or “virtual.” Instead, think in terms of work that happens at the same time (synchronous) or at different times (asynchronous), and collaboration that happens in the same or different places (remote).

Many collaboration practitioners tend to focus on synchronous collaboration — stuff that happens at the same time (which often ends up translating to meetings). I think some of the best opportunities for improving collaboration lie with asynchronous collaboration. Many of us assume that we can’t replicate the delightful experiences that are possible when people are in the same place at the same time. I think that’s narrow thinking.

Many years ago, I asked Ward Cunningham, the inventor of the wiki (the collaborative technology that powers Wikipedia), how he would describe the essence of a wiki. He responded, “It’s when I work on something, put it out into the world, walk away, and come back later, only to find that someone else has taken it and made it better.” To me, that beautifully describes what’s possible when asynchronous collaboration is working well, and it resonates with my own experiences. It also offers a North Star for what we’re trying to achieve when we’re designing for asynchronous collaboration.

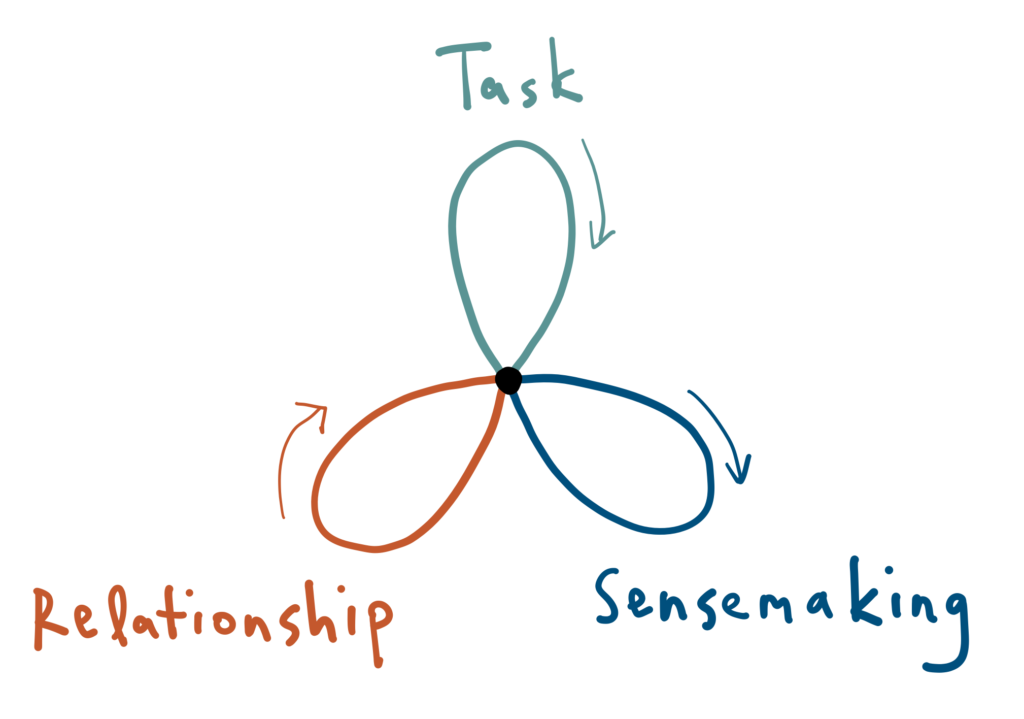

Second, it’s important to remember that collaboration consists of three different kinds of work: task, relationship, and sensemaking. Breaking collaboration into these three categories can offer greater guidance into how to design and facilitate asynchronous work more effectively.

For example, a common type of task work for knowledge workers is creating documents. Agreeing on a single place for finding and editing documents hugely simplifies people’s abilities to collaborate asynchronously. It also better facilitates the kind of experience that Ward described than, say, emailing documents back-and-forth.

A common sensemaking exercise is the stand-up meeting, where everyone on a team announces what they’re working on and where they need help. (People are asked to stand up during these meetings to encourage people to keep their updates brief.) You could easily do a stand-up meeting online, but aggregating and re-sharing status updates over email is potentially more efficient and effective.

One interesting side effect of so many people meeting over video while sheltering in place is that we literally get a window into each other’s homes and even our families and pets, an emergent form of relationship-building. Pamela Hinds , who has long studied distributed work, calls this “contextual knowledge” and has often cited it as a key factor for successful remote, asynchronous collaboration. (It’s why, when we were designing the Delta Dialogues, a high-conflict project focused on water issues in the Sacramento Delta, we chose to rotate the meetings at people’s offices rather than at a neutral location. We wanted people to experience each other’s workplaces to enhance their sense of connection with each other.)

Once we recognize this form of relationship-building as useful, we can start to think about how to do it asynchronously. In my Colearning community of practice, which consists of ten collaboration practitioners across the U.S. and Canada, each of us posts a weekly personal checkin over Slack, often sharing photos and videos of our loved ones. We post and browse at our own convenience, and the ritual and the artifacts forge bonds that run deeper than what would be possible with, say, a monthly video call, which would be incredibly hard to schedule and would almost certainly prevent some of us from participating.

Similarly, we don’t need video to see each other’s faces. A trick I stole from Marcia Conner many years ago — well before video was ubiquitous — was to get silly photos of everyone on the team, combine them in a document, and have everybody print and post it on their office wall. This not only enhanced our conversations when we were talking over the phone, it created a constant sense of connection and fun even when we weren’t in a room together.

While I hope these examples dispel the notion that synchronous collaboration is inherently more delightful and impactful than asynchronous, I also want to acknowledge that designing for asynchronous collaboration is more challenging. I think there are two reasons for this.

First, you have to compensate for lack of attention. When everyone is in a room together, it’s easier to get and keep people’s attention. When people are on their own, you have no control over their environment. You have to leverage other tools and techniques for success, and you’re unlikely to get 100 percent follow-through.

The two most common tools for compensating for lack of attention are the artifact and the ritual. An artifact is something tangible, something that you can examine on your own time, whether it’s a written document, a picture, or Proust’s Madeleine. A ritual is an action — often with some cultural significance — that’s repeated. It could be a rule (with enforcement) or a norm that people just do. It’s effective, because it becomes habitual, which means people are able to do it without thought.

The trick is finding the right balance of artifacts and rituals. At Amazon, Jeff Bezos famously requires people to write a six-page memo before meetings, but they designate shared time at the beginning of each meeting to read the memo together. On the one hand, writing the memo requires discipline and attention in-between meetings, or asynchronously. On the other hand, rather than save meeting time by having people read the memos beforehand, they devote synchronous time to reading the memos together. I can guess the reasons for this, but the truth is that I don’t know what they are. Different practices work in different contexts. Everybody has to figure out what works for themselves. Certain kinds of cultures — especially transparent, iterative, developmental ones — will be more conducive to these kinds of practices.

Finally, our relationship to technology matters, but maybe not in the way you think. On the one hand, if you are going to use a tool for collaboration, then it’s important to learn how to use it fluently and wield it skillfully. On the other hand, technology has this way of making you forget what you already know. It may be that the tools that will be most helpful for you have nothing to do with the latest and greatest digital technology.

This has always been easy for me to understand, because I have always had an uncomplicated relationship with technology. I love technology, but its role is to serve me, not the other way around. When I design structures and processes for collaboration, I always start with people, not tools, and I try to help others do the same.

What I’ve come to realize over the years is that this is often hard for others, because they’re worried about what they don’t know and they have a block when it comes to learning about technology. I get this. I have blocks about learning many things, and I know that advice that amounts to “get over it” is not helpful. Please recognize that these feelings are not only real, they’re okay. While I’d encourage everyone to find peers and resources that help them learn about digital tools in a way that feels safe, I also want to remind you that collaboration is ultimately about people. Keeping your humanity front and center will not only help you with your transitions to remote work, it will help you through this crisis.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: RSS