I am passionately committed to helping as many people as possible get better at collaboration. Within this larger mission, I am most interested in helping groups collaborate on our most complex and challenging problems. Over the past 17 years, I’ve gotten to work on some crazy hard stuff, from reproductive health in Africa and Southeast Asia to water in California. I’ve learned a ton from doing this work, I continue to be passionate about it, and I’ve developed a lot of sophisticated skills as a result.

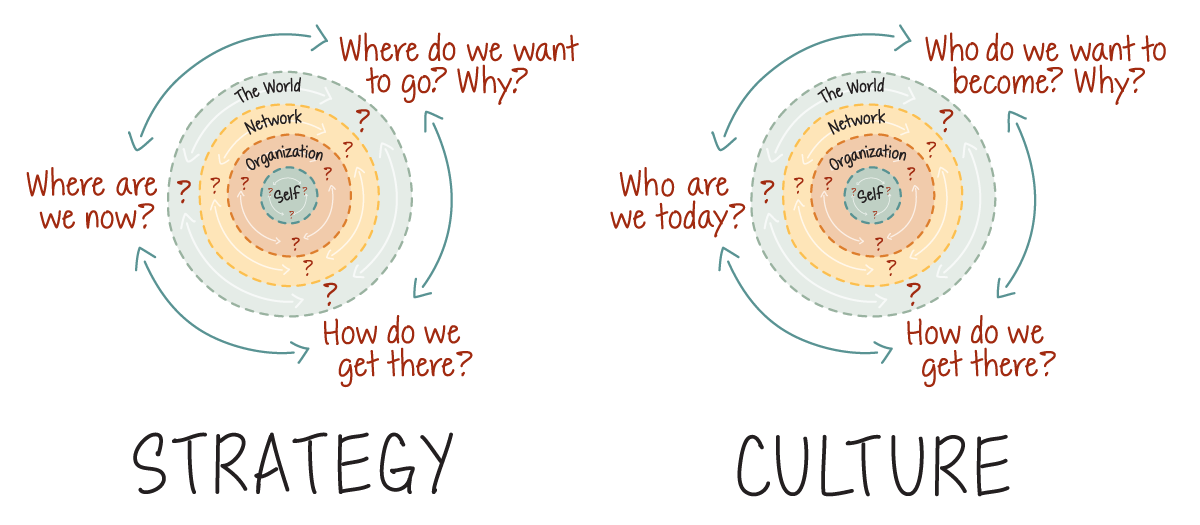

However, for the past year, I’ve been focusing most of my energy on encouraging people to practice setting better goals and aligning around success. My Goals + Success Spectrum is already my most popular and widely used toolkit, and yet, through programs like my Good Goal-Setting workshops, I’ve been doubling down on helping people get better at using it and — more importantly — making it a regular habit.

I’ve been getting a lot of funny looks about this, especially from folks who know about my passion around systems and complexity. If I care so much about addressing our most wicked and challenging problems, why am I making such a big deal about something as “basic” and “easy” as setting better goals and aligning around success?

Because most of us don’t do it regularly. (This included me for much of my career, as I explain below. It also includes many of my colleagues, who are otherwise outstanding practitioners.)

Because many who are doing it regularly are just going through the motions. We rarely revisit and refine our stated goals, much less hold ourselves accountable to them.

Because much of the group dysfunction I see can often be traced to not setting clear goals and aligning around success regularly or well.

Because doing this regularly and well not only corrects these dysfunctions, it leads to higher performance and better outcomes while also saving groups time.

And finally, because doing this regularly and well does not require consultants or any other form of “expert” (i.e. costly) help. It “simply” requires repetition and intentionality.

Investing in the “Basics” and Eating Humble Pie

In 2012, I co-led a process called the Delta Dialogues, where we tried to get a diverse set of stakeholders around California water issues — including water companies, farmers and fishermen, environmentalists, government officials, and other local community members — to trust each other more. Many of our participants had been at each other’s throats — literally, in some cases —for almost 30 years. About half of our participants were suing each other.

It was a seemingly impossible task for an intractable problem — how to fairly distribute a critical resource, one that is literally required for life — when there isn’t enough of it to go around. I thought that it would require virtuoso performances of our most sophisticated facilitation techniques in order to be successful. We had a very senior, skilled team, and I was excited to see what it would look like for us to perform at our best.

Unfortunately, we did not deliver virtuoso performances of our most sophisticated facilitation techniques. We worked really hard, but we were not totally in sync, and our performances often fell flat. However, something strange started to happen. Despite our worst efforts, our process worked. Our participants gelled and even started working together.

Toward the end of our process, after one of our best meetings, our client, Campbell Ingram, the executive officer of the Delta Conservancy, paid us one of the best professional compliments I have ever received. He first thanked us for a job well done, to which I responded, “It’s easy with this group. It’s a great, great group of people.”

“It is a great group,” he acknowledged, “but that’s not it. I’ve seen this exact same set of people at other meetings screaming their heads off at each other. There’s something that you’re doing that’s changing their dynamic.”

My immediate reaction to what he said was to brush it aside. Of course we were able to create that kind of space for our participants. Doing that was fundamental to our work, and they were all “basic” things. For example, we listened deeply to our participants throughout the whole process and invited them to design with us. We co-designed a set of working agreements before the process started, which was itself an intense and productive conversation. We asked that people bring their whole selves into the conversation, and we modeled that by asking them very basic, very human questions, such as, “What’s your favorite place in the Delta?” and “How are you feeling today?” We rotated locations so that people could experience each other’s places of work and community, which built greater shared understanding and empathy. We paired people up so that folks could build deeper relationships with each other between meetings.

These were all the “basic” things that we did with any group with which we worked. I didn’t think it was special. I thought it was what we layered on top of these fundamentals that made us good at what we did.

But in reflecting on Campbell’s compliment, I realized that I was wrong. Most groups do not do these basic things. For us, they were habits, and as a result, we overlooked them. They also weren’t necessarily hard to do, which made us undervalue them even more. Anyone could open a meeting by asking everyone how they were feeling. Only a practitioner with years of experience could skillfully map a complex conversation in real-time.

I (and others) overvalued our more “sophisticated” skills, because they were showier and more unique. However, it didn’t matter that we were applying them poorly. They helped, and they would have helped even more if we were doing them well, but they weren’t critical. Doing the “basics” mattered far more. Fortunately, we were doing the basics, and doing them well.

Not doing them would have sunk the project. I know this, because we neglected a basic practice with one critical meeting in the middle of our process, and we ended up doing a terrible job facilitating it despite all of our supposed skill. The long, silent car ride back home after that meeting was miserable. I mostly stared out the window, reliving the day’s events over and over again in my head. Finally, we began to discuss what had happened. Rebecca Petzel, who was playing a supporting role, listened to us nitpick for a while, then finally spoke up. “The problem,” she said, “was that we lost sight of our goals.”

Her words both clarified and stung. She was absolutely right. We knew that this meeting was going to be our most complex. We were all trying to balance many different needs, but while we had talked about possible moves and tradeoffs, we hadn’t aligned around a set of collective priorities. We each had made moves that we thought would lead to the best outcome. We just hadn’t agreed in advance on what the best outcomes were, and we ended up working at cross-purposes.

I was proud of Rebecca for having this insight, despite her being the most junior member of our team, and I also felt ashamed. I often made a big deal of how important aligning around success was, but I had neglected to model it for this meeting, and we had failed as a result.

Habits Are Hard

After the Delta Dialogues, I made a list of all the things I “knew” were important to collaborating effectively, then compared them to what I actually practiced on a regular basis. The gap wasn’t huge, but it wasn’t trivial either. I then asked myself why I ended up skipping these things. The answer generally had something to do with feeling urgency. I decided to try being more disciplined about these “basic” practices even in the face of urgency and to see what happened.

I was surprised by how dramatically the quality and consistency of my work improved. I was even more surprised by how slowing down somehow made the urgency go away. The more I practiced, the more engrained these habits became, which made them feel even more efficient and productive over time.

In 2013, I left the consulting firm I had co-founded to embark on my current journey. Helping groups build good collaborative habits through practice has become the cornerstone of my work. Anyone can easily develop the skills required to do the “basics” with groups. They just need to be willing to practice.

I’ve identified four keystone habits that high-performance groups seem to share:

- Align around success

- Align around working agreements

- Assess performance (i.e. retrospectives)

- Organize and maintain information (i.e. information hygiene)

The specific manifestation of each practice isn’t that important. What matters most is for groups to do all four of them regularly and well.

Over the past six years, I’ve had decent success developing practices and tools that work well when repeated with intention. Unfortunately, I haven’t been as successful at encouraging groups to make these practices habits. As I mentioned earlier, I think one reason is that it’s easy to undervalue practices that seem basic. I think the biggest reason is that developing new habits — even if we understand them to be important and are highly motivated — is very, very hard.

In his book Better: A Surgeon’s Notes on Performance, Atul Gawande writes that every year, two million Americans get an infection while in a hospital, and 90,000 die from that infection. What’s the number one cause of these infections? Doctors and other hospital staff not washing their hands.

For over 170 years, doctors have understood the causal relationship between washing their hands and preventing infection. Everybody knows this, and yet, almost two centuries later, with so many lives at stake, getting people to do this consistently is still extremely hard, and 90,000 people die every year as a result. Gawande explains:

We always hope for the easy fix: the one simple change that will erase a problem in a stroke. But few things in life work this way. Instead, success requires making a hundred small steps go right — one after the other, no slip-ups, no goofs, everyone pitching in. We are used to thinking of doctoring as a solitary, intellectual task. But making medicine go right is less often like making a difficult diagnosis than like making sure everyone washes their hands.

If it’s this hard to get doctors to wash their hands, even when they know that people’s lives are at stake, I don’t know how successful I can expect to be at getting groups to adopting these habits of high-performance groups when the stakes don’t feel as high.

Still, I think the stakes are much higher than many realize. I recently had a fantastic, provocative conversation with Chris Darby about the challenges of thinking ambitiously and hopefully when our obstacles are so vast. Afterward, I read this quote he shared on his blog from adrienne maree brown’s, Emergent Strategy:

Imagination is one of the spoils of colonization, which in many ways is claiming who gets to imagine the future for a given geography. Losing our imagination is a symptom of trauma. Reclaiming the right to dream the future, strengthening the muscle to imagine together as Black people, is a revolutionary decolonizing activity.

We all have the right to articulate our own vision for success. When we don’t exercise that right, we not only allow our muscles for doing so to atrophy, but we give others the space to articulate that vision for us. Hopefully, these stakes feel high enough to encourage groups to start making this a regular practice.

For help developing your muscles around articulating success, sign up for our Good Goal-Setting online peer coaching workshop. We offer these the first Tuesday of every month.