This past year, I had the chance to shadow my friend and colleague, Odin Zackman, for the June and October sessions of the Water Solutions Network, a leadership development program for mid-career leaders focused on California water issues. The program was facilitated by Odin, Donald Proby, and Celeste Cantu, and managed by Angela Pang.

Their second cohort, consisting of 24 wonderful participants, had spent several months working on a group project focused on the Human Right to Water. Watching a group that large try to self-organize can be an awkward exercise, but this group had a special chemistry, and watching them work was one of the highlights of my experience.

The October session was their final meeting, and they were scheduled to present their project to a room full of guests and VIPs. The morning of their presentation, the group did a one-word checkin. Most people expressed enthusiasm and excitement. The one exception was a participant whose word was “stressed.” That made everyone laugh. This participant was outwardly quiet and composed, and she was well loved by her peers, so no one was taken aback by her sentiment. To the contrary, I think that people appreciated it, as others were feeling the same, and hearing her say it out loud helped defuse it.

The presentation was superb. The next morning, when folks were reflecting on how it went, this same participant referred back to her checkin the previous day. She talked about how one of her peers came up to her afterward and gave her a hug and told her that everything would be okay. She talked about how worried she was about things going awry during prep, then how she saw how everything was coming together nicely, with folks acting with creativity and care to address challenges as they arose, in some cases differently than she would have but no less effectively. She talked about how empowering that was and how she needed more of that in her work and in her life. Then she broke down and started crying. So did most of the room. So did I.

The professional world of water is full of engineers and government agencies, about as far from touchy-feely as you can get. It’s conservative, rules-based, and rigid. It was so clear from both sessions I watched and from this moment in particular how huge it was for this group to escape from that culture, to let go of control and orthodoxy, and to just trust each other.

Watching this group break down the way it did, seeing the heavy burden that many of them carried and the relief they felt when the burden was off their shoulders really hit home for me. I was moved by the moment and by the joy they felt from performing together in this way, but I also felt guilt and shame as I thought about moments when I, as a leader, had created the opposite experience for people who had worked with me.

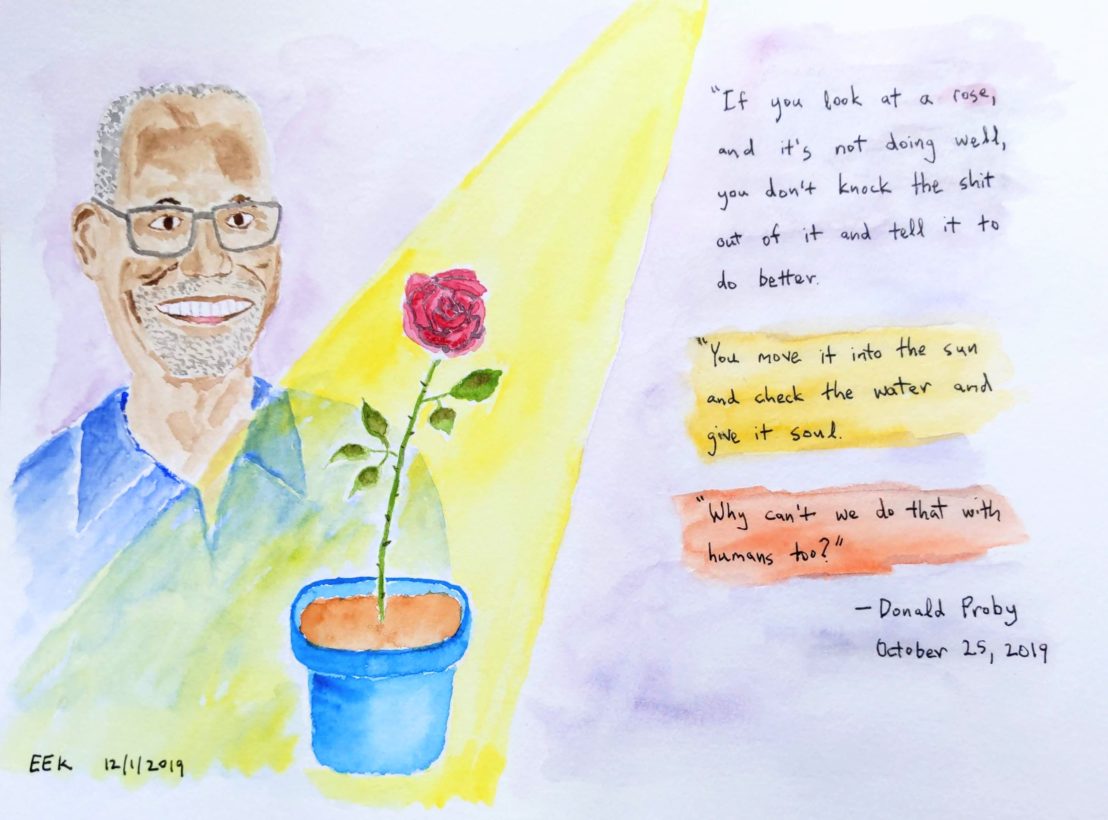

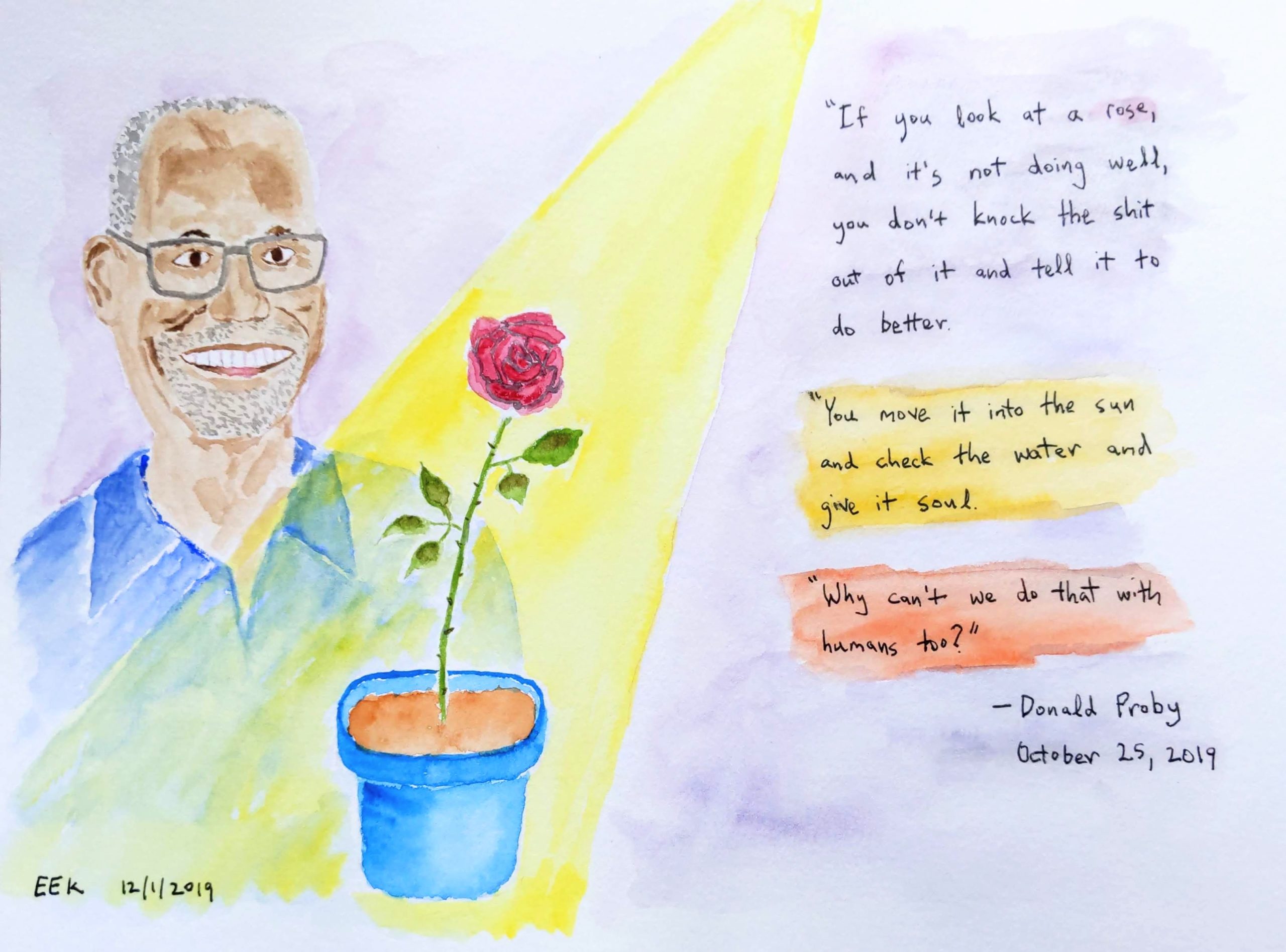

I know Odin well and wasn’t surprised that he had skillfully built and held a space that enabled the participants to free themselves and to trust each other. I didn’t know Donald at all before these sessions, and I was struck both by his energy and the relationships that he had developed with these participants. Donald loved everyone, and everyone loved him back. Several of them cited how much his words and his way of being had impacted them.

In his final checkout to the group, Odin, who has a beautiful way with words, laughingly acknowledged the Donald love-fest, saying that it made perfect sense, because Donald was “made of love.” Odin then talked about how that love comes through in the work, and compared it to a meal that one’s grandmother might make. His stories hit me in the heart and in the gut, stirring up all sorts of new feelings. This concept of “made of love” resonated so strongly while also embodying a tension that I struggle with as a leader. Just because something is made of love doesn’t mean that it feels that way.

When I hear “made of love,” I think of my 79-year old mom’s kimchi — how she goes directly to Korea to source certain ingredients, often traveling far and wide to visit the best vendors, how she meticulously washes and salts every leaf of cabbage, how she stays up all night chopping and processing all of the ingredients just so, so that when she finally and vigorously massages them together, they create the perfect balance. She doesn’t have some sort of obsessive compulsive disorder, nor is she swimming in free time. She does all this because she’s making kimchi for me and my sisters, whom she loves more than anything, and because that is how she expresses her love.

My mom is made of love, and so is her food. But there’s a cost to this kind of love. It takes a lot of work, and it requires some hard tradeoffs and sacrifices. Moreover, not everyone can feel the love. To some, all kimchi, whether store-bought or handmade, tastes more or less the same. It doesn’t matter how it’s made or by whom. To those who feel that way, the end result doesn’t justify the labor, the sacrifices, or the strife.

My mom raised me and my sisters the way she made kimchi. We, too, are made of love, but we didn’t always experience it that way. My mom was highly critical of us when we were growing up. Still is, actually. She wanted the best for us, she knew how difficult our journey would be as children of immigrants with limited means and connections, and she had experienced deep trauma in her own life that she wanted us to avoid. She could be harsh and demanding. In the best of times, my sisters and I understood that this was her way of expressing her love, but we also suffered from it. Still do.

We all have different ways we like to express and receive love. It’s what makes relationships and family in particular so challenging. The problem is that love, when not executed with care and deep consideration of the other person, is not love, regardless of the intent. At its best, it’s harshness. At its worst, it’s violence. I know this first-hand. I think most of us do.

People need to choose for themselves whether or not to imbue their work with love and how to express that love. I love my work, and I approach it the same way my mom makes kimchi. I do my best to be transparent about what that means to me, so that people can choose whether or not they want to work with me. But that’s only the first step of a long, ongoing journey. You still have to take the time to deeply understand the people you work with. You have to be aware of your impact on others, regardless of your intent. You have to find ways to manage that impact while staying true to whom you are.

This is the work. And it’s really, really hard.

I try to create environments for my teams where everyone feels seen, trusted, and loved. I’m also intense, and I hold myself and my teams to a very high standard. I’m proud of this, I think it’s consistent with my values, and I have no intention of changing. Most people I work with know and value this too. Not everyone wants to be held to these standards, and those folks should simply not work with me (and generally don’t).

However, when conflict has arisen (and it always does), it’s been difficult to unpack whether it’s been about differing standards or a result of my communication style (blunt and sometimes unskilled) and energy (again, intense). I’ve worked really hard over the years to be more conscious of this, and I continue to work hard to find the right balance, but it’s not easy, and I’ve hurt a lot of people along the way. I can’t say definitively whether I was right or wrong in those cases (or if that’s even the correct way of thinking about it), but I know for certain that, regardless of my intentions, deep in my heart, I feel shame and incredible sadness for ever making anyone feel that way.

What impressed me so much about Donald was not just how clearly love was at the center of everything he did, but how much we all (me included) felt his love and the impact of that love on the group as a whole. I can’t ever be like Donald, but I can strive to have my teammates experience my love in similar ways. I think that would have a profound impact on my work and my relationships.

I also don’t want people to think that love is everything.

Watching the Water Solutions Network cohort work on its final project was magical, but it wasn’t solely because of the container that Odin, Donald, Celeste, and Angela created, or because the participants cared about their final project and each other, or because they — and their facilitators — were made of love. All of those things happened to be true, and they all mattered, but they weren’t the only reason they all worked together so well. They worked together well, because they were all talented and skilled, because they all had similarly high standards, because they had the right amount of diversity, and because… well, because they also got lucky.

If any one of those factors were even slightly off, it wouldn’t have been nearly the same experience. All that love mattered, but it wasn’t sufficient. The best work happens when love is at the core, but if you don’t have the other factors as well, that can exacerbate the harsher aspects of love. There are a whole slew of collaboration practitioners who are most definitely made of love, but who are terrible at the work, because they don’t understand this.

Fortunately, I think most of the people I work with already know that love alone doesn’t make the work sing. As a leader, I want to support my teams in tapping into their love, so that the work is imbued with it. I want them to love, but also feel loved. Love does not always feel good, but it should always feel safe. Striking that balance is hard, and there aren’t a lot of models for doing it well. I feel blessed to have had the opportunity to experience that balance through Odin, Donald, Celeste, Angela, and the entire Water Solutions Network cohort’s leadership and example. They are all indeed made of love.

Thanks to H. Jessica Kim, Travis Kriplean, and Eun-Joung Lee for reviewing earlier versions of this draft, and to Denise Collazo, whose stories of forgiveness inspired me to share this.