Two of my mentors, Gail and Matt Taylor, often stress the importance of “clean beginnings.” Whenever you take on any hard, collaborative project, you have to expect that it will get messy in the middle. If you take the time to set up conditions for success at the beginning of the project, you will greatly increase your chances of surviving — even thriving in — that mess. Folks in this business often refer to this as “creating a safe container.”

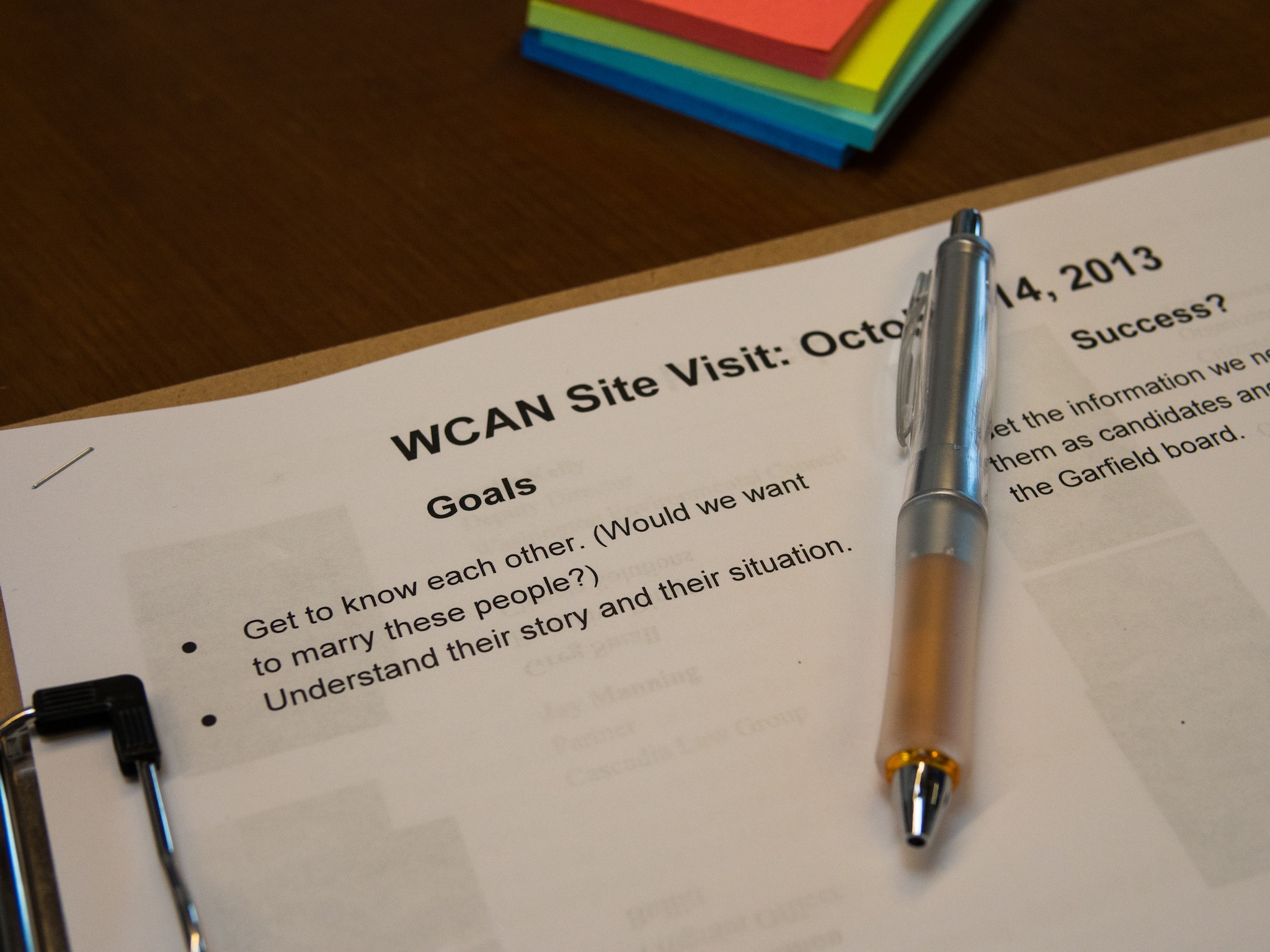

I’m in the process of doing this with two projects right now — an experiment with the Code for America Incubator Program and the kickoff of Garfield Foundation’s latest Collaborative Networks initiative — and I wanted to share some of my experiences in “the art of the start” from these and other projects.

Creating a safe container consists of three activities:

- Literally creating a delightful, inviting space (physical, virtual, or both) in which the group can interact

- Developing shared understanding among the group

- Making explicit working agreements.

When done effectively, these three things in combination lead to greater trust within the group, which enables it to work effectively moving forward.

1. Create Delightful, Inviting Space

The physical spaces in which we work have a huge impact on our ability to work effectively. Dark, tight spaces affect the mood of the group. The seating arrangement can physically reinforce certain power dynamics. If it’s hard to get to the whiteboard, people won’t use it.

These issues don’t just apply to physical space. If your group has a weekly two-hour phone call with poor audio quality and no shared display, people will dread (or simply tune out) those calls. If you’ve chosen to interact using an online tool that nobody knows how to use, then no one will use it.

Spatial issues may seem trivial, but I think they are just as important as facilitation. In 2012, I co-led a project called the Delta Dialogues, where we were facilitating a multistakeholder group around California water issues. Our participants had been fighting over these extremely contentious issues for decades, and many had standing lawsuits with each other.

One of the early decisions we made was to rotate our meeting locations among the participants rather than seek “neutral” space. We had six one-day meetings scheduled, and we decided to devote half that time to “learning journeys” — essentially tours of each others’ spaces. We did this because the Sacramento Delta is beautiful, and we wanted to spend as much time as possible in that beauty to remind ourselves what this was all about. We also did this wanted participants to experience each other’s environments first-hand to build greater empathy.

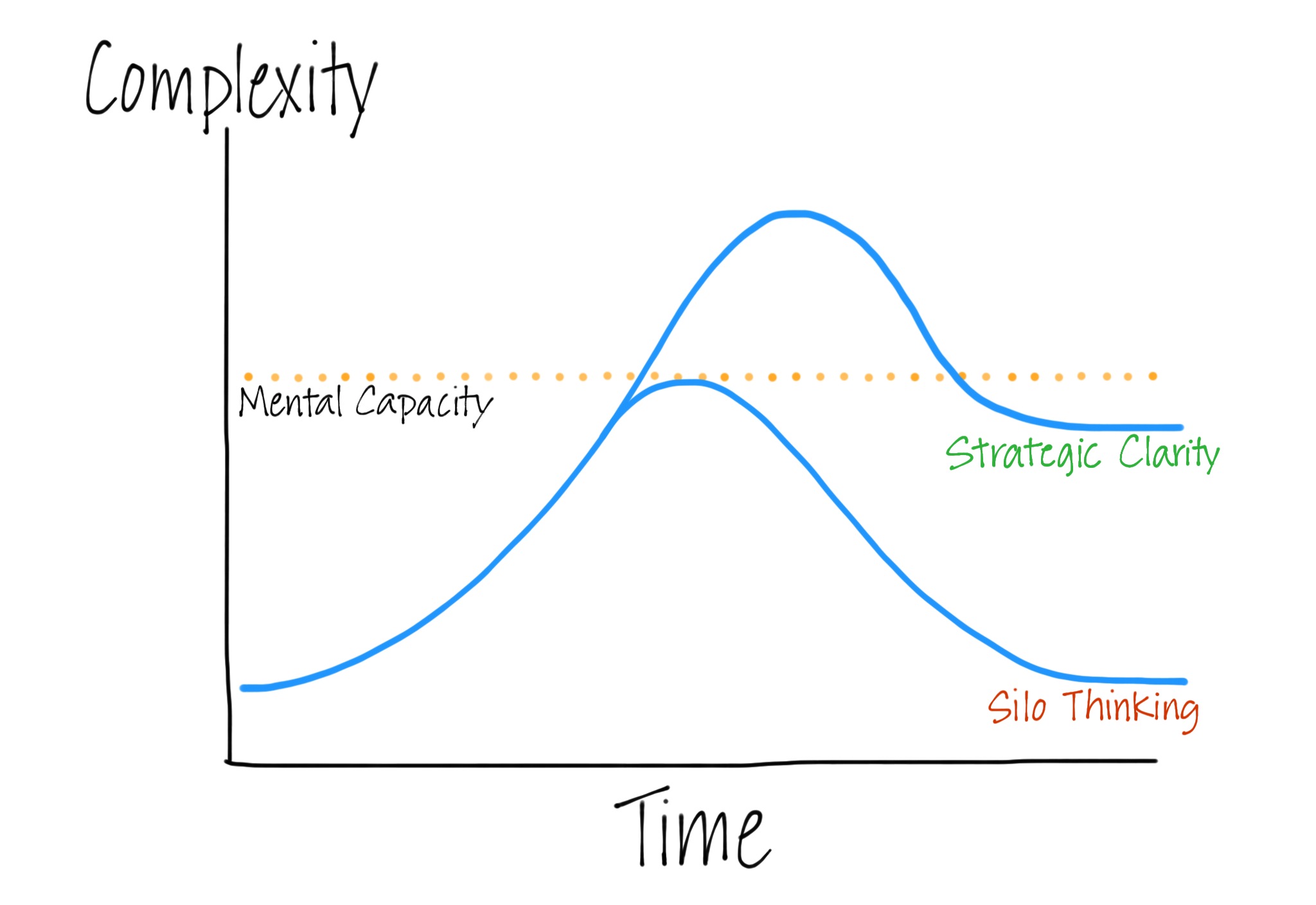

This was not a decision we made lightly. Given the complexity of the issues we were discussing, devoting half of our times to field trips felt hard to swallow, and we went back and forth on this decision a number of times. However, when the process was over, participants consistently cited these learning journeys as the most powerful part of the process for them.

Rick Reed, the leader of the Garfield Foundation’s Collaborative Networks initiative, feels as strongly about the importance of the physical experience as I do. He seeks out great meeting space with beautiful light, and he makes sure that the food is excellent and memorable. Some people do not think foundations should be spending money on things like great space and food in light of the economic hardships the nonprofit sector is currently facing. While I am a fan of fiscal discipline, if foundations want to contribute to great collaborative experiences, I think investing in great space and great food are two of the easiest and most impactful ways to do that.

Creating an inviting, delightful space is not just about physical or even virtual space. Language, for example, is a big part of this. I often use the term “ground rules” to describe working agreements (see below), but when I used the term at a Collaborative Networks design meeting, our teammate, Ruth Rominger, pushed back. She thought the implications of “rules” ran counter to the culture we were trying to build. On Curtis Ogden’s suggestion, we decided to adopt the term “working agreements” instead, which is more inviting, but still meaningful.

2. Develop Shared Understanding

The group norming process is about developing shared understanding, which leads to greater trust and stronger relationships. The default way to build shared understanding is to work together. There are great merits to this, but they are easily neutralized or worse if you don’t take the time to have explicit conversations about norms as well.

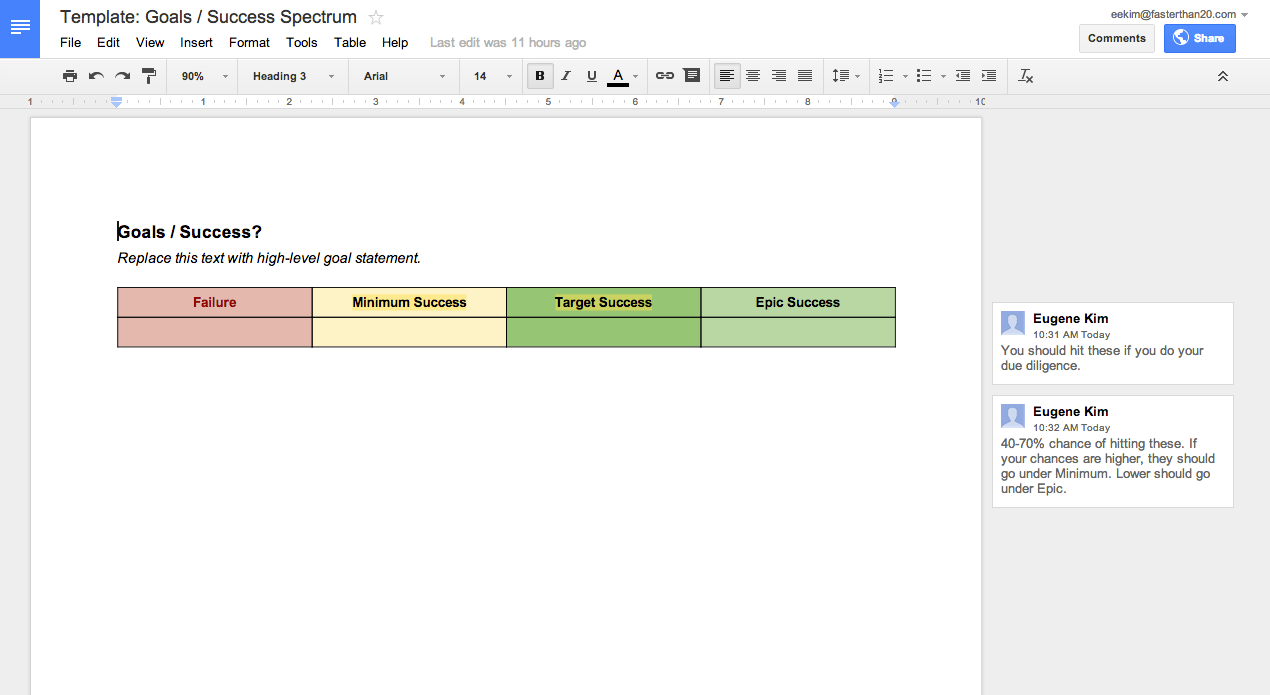

For example, when I worked as a consultant, I spent a significant amount of time helping stakeholders get aligned and clear around the goals of the project. It was a straightforward, but time-consuming step, one that most groups would skip if left to their own devices. And yet that step alone made a huge difference in the quality of the engagement once we got going. Often, individuals do not feel empowered or accountable to the rest of the group, simply because there is no shared understanding of what they’re supposed to be doing or what’s expected of them.

How do you develop this shared understanding? The simplest first step is to carve out time to have those conversations as a group. A huge part of my experiment with the Code for America Incubator is simply that — giving startups structured time to have explicit conversations about things such as what kind of organization they’d like to be and how they’d like to work together.

Beyond this, there are a few useful tricks. One is to tap into people’s personal experiences and values. Rather than start with the question, “How would you like to work together?”, ask each other, “What’s been your best experience working together?”, or better yet, “Why did you get into this work?” Have people share those stories with each other, then pull out key patterns and insights from the stories.

With the Delta Dialogues, we had participants answer the question, “What’s your favorite place in the Delta?” Many of the participants had known each other for decades, yet did not know each other’s answers to these questions. It reinforced the fact that everybody in the room (including the supposed “bad guys”) had deep connections to the Delta, and it reminded everybody about what was at stake.

Another trick is to design these experiences to be in-the-flow as much as possible. People who design collaborative engagements — consultants in particular — often make two mistakes: They focus too much on meetings, and they don’t pay enough attention to the work that participants are already doing. You’re almost never starting from scratch. People have pre-existing relationships, and they may already have done the work that you’re wanting to do.

I joined the Wikimedia strategic planning process in 2009. The Wikimedia Foundation had hired a traditional management consultancy four months earlier, and they were stuck. These consultants had no experience with participatory processes or with the Wikimedia community, and they had designed a process that was not viable. Their plan looked like most traditional strategic planning processes. They would spend four months doing research on their own and coming up with the “right” strategic questions, then they would unleash a polished presentation to the community at large and ask for feedback.

Not only did this approach not account for the spirit of the project (wiki-style strategic planning) or the culture of the community, it completely ignored the challenge of enrollment. The Wikimedia editing community consisted largely of men in their teens and twenties. They had no concept of what strategic planning was, much less why they should engage in it. Even if they did understand what strategic planning was, they had no reason to engage with us about it. Why should they trust our claimed intentions to facilitate an open, wiki-style process?

I wanted to develop a shared understanding of the work that had already been done, and I also wanted to develop a shared understanding around what we were trying to do with this process. Rather than wait four months to do research in isolation, within a week of starting the project, we were engaging with the community on a wiki. We explained what we hoped to do, and we listened. We didn’t make grand promises, and we didn’t claim any expertise. We basically invited people to tell everybody (not just us) what they thought the Wikimedia movement’s priorities should be and to point to work that was already happening.

In the spirit of creating an inviting container, our facilitator, Philippe Beaudette, stressed the importance of making our space multilingual, given how international the community was. We invited people to engage in any language with which they felt comfortable, and we did our best to translate our requests into as many languages as possible.

We had a clear ask, and that ask felt very familiar to the Wikimedia community. They were used to sharing and organizing their thoughts, and they were not shy about expressing their opinions. Within a few weeks, we had an incredible compendium of well-organized thinking that had already been done by the community, along with a set of thoughtful, strategic questions that people felt were important to explore.

More importantly, people started trusting us. They saw that we got it, that we weren’t going to try to impose something top down on a movement that was inherently bottoms-up. (We would have failed if we tried.) We didn’t try to have some grand kickoff meeting or to facilitate a bunch of private, insider conversations. Instead, we spent time in the spaces that already existed (such as the wiki and in real-time online chat channels), and we facilitated a many-to-many conversation, not just a one-on-one conversation. The community was taking ownership of the process, and we were contributing to it. Even if they didn’t fully understand what we were trying to do, they understood it well enough and they trusted us enough to give it a chance.

3. Make Explicit Working Agreements

I find making explicit agreements on how you’d like to work together to be one of the most valuable things a group can do, whether it’s a small team or a large network.

For example, some might think that “treating other people with respect” should be implicit in every working arrangement. Even if that’s the case, making it explicit can’t hurt, and it can even help. For one, it forces you to develop some shared understanding around what “treating other people with respect” actually means. To some, it might mean never raising your voice. To others, it might have nothing to do with how you express yourself, only that you do. Getting these things out into the open earlier rather than later, then coming to agreement on them will prevent trouble later on.

Establishing working agreements has two other important effects, especially with larger groups. First, it makes everyone accountable for holding him- or herself and each other to these agreements. Often, in large meetings, people depend on a facilitator to keep the conversation constructive and civil. That indeed is one of the facilitator’s responsibilities, but it’s a muscle that everyone in the group should be exercising. In healthy groups, everybody will help each other abide by these agreements.

Second, they set agreed-upon conditions for kicking people out of a group. A lot of people fear open processes, because they’re worried that others will hijack the conversation, and they mistakenly assume that you can’t kick people out of an open conversation. If you create clear working agreements up-front, and if you make sure people are aware of those agreements, then when people unapologetically cross the line, you have the right to expel them.

We had over a thousand people participate in the Wikimedia strategic planning process. Over the course of the year-long process, we kicked out two people from the process as a whole, and I kicked out one person from one meeting (who apologized afterward, and went on to be a very constructive participant in the process). None of those incidents were easy, but when we made those moves, everyone in the community understood and agreed with our actions, because of our previously established working agreements.

This blog post is also available in French. Many thanks to Lilian Ricaud for the translation!